6 Apr 2021

In the second of a three-part series looking at how COVID-19 has impacted on women working in the profession, WellVet co-founder and editor of Veterinary Woman Liz Barton looks at how coronavirus is affecting the mental health of women in the sector…

Image © insta_photos / Adobe Stock

Mental health should always be high on our agenda. One in four people will suffer from mental ill health in the next 12 months – and that statistic is for the general population and pre-COVID1.

The figures are likely to be even more concerning, both within our high-risk profession and due to the additional stresses of the pandemic. So where do the risk factors lie and how can we all help mitigate them?

It has been well documented that the veterinary profession is high risk for poor mental health and suicide. Evidence is also building that the well-being of female vets is lower than that of their male counterparts.

In a feminising profession, the mental health of our demographic should always be forefront of our thoughts. The Merck Animal Health Veterinary Wellbeing Study showed well-being scores for male vets was above that of men in other areas of work, whereas the converse was true for female vets2.

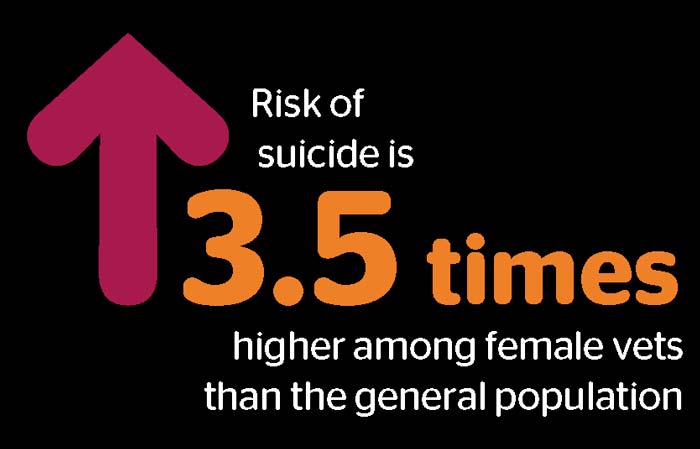

Women are also more prone to stress, compounded by the fact they are exposed to additional stressors such as gender inequality and bias in the workplace. Alarmingly, research showed risk of suicide is 3.5 times higher among female vets than the general population, elevated to a greater extent than for male vets who are at a 2.1 times increased risk2,3.

I’m raising this to highlight how important it is that we delve into the reasons why women are more at risk of mental ill health. That knowledge is key to both prevention and providing effective support.

In the general population, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that overall rates of psychiatric disorder are almost identical for men and women, but striking gender differences are found in the patterns of mental illness4.

Women are more likely to have been treated for a mental health problem than men (29% compared to 17%)5. This could be because women are more likely to report symptoms of common mental health problems.

Depression, anxiety and OCD are reportedly more common in women than men6. A staggering 25% of women will require treatment for depression at some time, compared to 10% of men.

Unipolar depression, predicted to be the second leading cause of global disability burden by 2020, is diagnosed twice as frequently in women than men. It may also be more persistent in women4. Conversely, the prevalence for alcohol addiction is twice as high in men than in women, and personality disorders are three times more likely to affect men.

Gender-specific risk factors for diagnosis of common mental disorders that disproportionately affect women include gender-based violence, socio‑economic disadvantage, low income and income inequality, low or subordinate social status and rank, and unremitting responsibility for the care of others.

Many of these factors have been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. Cases of domestic violence have risen, with approximately 80% of victims being female7.

As we have seen, it is women whose incomes have suffered the most. It is also women who are more likely to be furloughed or lose their jobs altogether, contributing to feelings of frustration and inadequacy at further subordination of social status. And, of course, women are bearing the brunt of the additional childcare responsibilities and, indeed, are more likely to be involved in the care professions.

The WHO also stated that “reducing the over‑representation of women who are depressed would contribute significantly to lessening the global burden of disability caused by psychological disorders”. The world could certainly do with reduced burdens moving forwards.

While we may not be surprised to hear lockdown is having a negative impact on mental health, it is concerning this effect is far greater for women.

A new study by the universities of Cambridge, Oxford and Zurich revealed the fall in mental health in US states during lockdown could be explained entirely by the demise in the mental health of women. Men experienced small and statistically insignificant alterations, whereas women reported significant declines. The gender mental health gap has risen to 66%8.

A study by King’s College London showed 57% of women said they were feeling more anxious and depressed, compared with 40 per cent of men. More women than men reported they were sleeping less and eating less healthily than usual9.

I can relate to this – my sleep patterns have been all over the place as I shoehorn work into the early and late hours. Also, my jelly sweet consumption has never been higher (it was practically nil before and now it’s, well, a lot).

Here’s the rub: gender stereotyping regarding proneness to emotional problems in women appear to reinforce stigma and constrain help-seeking. This is particularly true when a hormonal element exists, which can be significant and severe10.

Such stereotypes are a barrier to accurate identification and treatment of psychological disorders. Doctors are more likely to diagnose depression in women than with men, even when they present with identical symptoms. Being female is, in itself, a significant predictor for being dispensed mood-altering or psychotropic medication4.

If any of the issues raised in this article strike a chord with you personally, please contact Vetlife for confidential advice and support.

As practices and individuals, the first action to support anyone is always to ask – ask if he or she is okay, with time and space to answer. Ask again, and regularly. Cultivate a culture of openness where mental health is not stigmatised – and call it out when it is. Champion well-being and put in place measures to support your team.

These do not have to be complex or costly; plenty of practical examples to suit all sizes and shape of practice can be found through the SPVS/Mind Matters practice well-being award booklets and articles11. Above all, make it a priority. After all, people are the greatest practice asset, with value beyond compare.

Awareness is the first step to addressing problems, so thank you for reading. Those interested in a more in-depth discussion of the issues in this article can read the full version at Veterinary Woman.

We want to hear your experiences and ideas on how we can better facilitate women in the workplace through and beyond COVID-19. To be representative we need diverse representation, and would like to invite women from across the industry to take part.

Follow our Facebook page for upcoming polls to feed into this work, and to share your story or contribute, email [email protected]

Vetlife Helpline offers confidential emotional support to everyone in the veterinary community. It is available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Anything you discuss is confidential and you don’t have to use your real name.

To get in touch with Vetlife, telephone 0303 040 2551 or email anonymously via vetlife.org.uk