18 Sept 2023

John Innes BVSc, PhD, CertVR, DSAS(Orth), FRCVS in the first of this two-part series, considers how the right radiographic approach can enhance care for dogs.

Disease of synovial joints in dogs is common, and radiography is one of the major routes to diagnosis in general practice.

In the first of two respective articles on the thoracic and pelvic limbs, the author will review the key features of joint disease as seen radiographically. Knowledge of the early, and sometimes subtle, changes that can been seen on radiographs can improve diagnostic yield and maximise the insight that radiographic examination can provide.

Optimising the quality of radiography and radiological interpretation can enhance the value that clients receive from such examinations, and sharing of images with clients can improve understanding of the conditions and the subsequent choices open to them.

Thoracic limb lameness is common in dogs. An old adage says that thoracic limb lameness is “in the elbow joint until proven otherwise”. Such sayings can be helpful and unhelpful in, perhaps, equal measure, and one should maintain an open mind with every case of thoracic limb lameness.

While clinical signs such as a palpable joint pain response can sometimes lead the clinician towards imaging of a specific joint, it is also frequently the case that the clinical examination is unhelpful and one is left with the prospect of screening the entire limb.

That said, the author would encourage every effort be made to narrow down the seat of the lameness, such that any radiological findings have a clinical context.

Accepting that clinical examinations of dogs can be unreliable, one should consider repeated examinations, opinions from colleagues and even local intra-articular blocks (under sedation and reversal).

Signalment can also be useful in informing the radiological examination, but again, one should be wary of the bias that too much reliance on knowledge of breed predisposition to certain joint diseases can bring.

Radiography has been one of the mainstays of veterinary diagnostics for decades; it is very available and relatively cost effective.

However, like all diagnostic modalities, radiography has limitations, such as being a two-dimensional projection of a three-dimensional structure and relatively poor ability to differentiate soft tissues.

An understanding of the limitations of radiography in the context of common canine joint diseases is useful.

The standard views for the shoulder joint are mediolateral and craniocaudal projections. Positioning for the mediolateral view is best achieved with the index limb protracted, the contralateral limb tied in a retracted position, and the neck dorsiflexed. Ideally, the index limb should be protracted such that the trachea is not superimposed on the shoulder joint. However, sometimes tracheal superimposition can enhance contrast.

The canine shoulder joint is a less common seat of thoracic limb lameness compared to the elbow joint. However, young dogs of larger breeds can be affected by osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), which can affect the humeral head, and sometimes the glenoid. OCD of the humeral head can usually be seen on plain radiographs (Figure 1). The majority of OCD lesions seen on plain radiographs will be associated with pain and clinical signs.

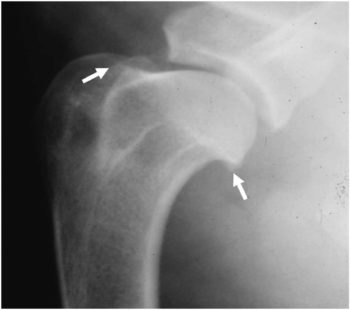

The other most common changes seen on canine shoulder joints would be non-specific osteophytosis (Figure 2), a marker of osteoarthritis. Osteophytes in the shoulder joint often are most easily observed at the caudal aspect of the humeral head and the caudal margin of the glenoid. In addition, osteophytosis may also be seen superimposed on the bicipital tendon groove.

Interpreting osteophytosis of the shoulder joint is not always straightforward. Osteophytosis can indicate idiopathic osteoarthritic pathology and this can be clinically incidental, or clinically meaningful. Here, the author returns to the previous discussion on clinical context. Osteophytosis may also indicate joint instability, associated with damage to the soft tissue supporting structures of the shoulder joint. Further investigation of such an aetiology may require advanced imaging modalities such as arthroscopy or MR arthrography.

Although the term “elbow dysplasia” is commonly used to group development conditions together, the author would argue this is unhelpful in that it can hinder critical thinking regarding conditions that may have very different risk factors and aetiologies.

The standard projections for the elbow joint are the (flexed) mediolateral view and the craniocaudal view.

The mediolateral view is relatively straightforward with the index limb against the x-ray table and the contralateral limb tied well back in a retracted position. It helps to dorsiflex the neck.

It can be helpful to take both flexed and neutral or extended mediolateral views because this will help to skyline the proximal border of the anconeal process and the radial head, respectively (Figures 3a and 3b).

The craniocaudal view can be prone to positional challenges and the use of positioning aids will help to ensure a straight craniocaudal projection is achieved.

If radiation protection officer permission is in place, a horizontal beam with the patient in lateral recumbency can be an easier and more repeatable position. However, one must be certain appropriate radiation protection infrastructure and measures are in place prior to using this method.

In young dogs, it is radiographic signs of developmental disease that one may wish to particularly look out for in the canine elbow.

While some primary lesions are visible, the most common developmental disease is medial coronoid disease (MCD) and it is not generally possible to see the primary lesion because the area is obscured by superimposed radial head. Therefore, it is secondary osteophytosis or subchondral sclerosis that must be relied on to identify the elbow as pathologic.

OCD of the medial humeral condyle is uncommon, but can usually be seen as a defect in the subchondral bone line on the craniocaudal projection (Figure 4).

Ununited anconeal process is also an uncommon condition of medium-large breed dogs. The anonceal process should be fused by 16 weeks of age and the condition is best detected on a flexed mediolateral projection (Figure 5).

The major developmental disease of young dogs is MCD. A study of young dogs with painful elbows reported that 88% were associated with coronoid disease in some form1.

Coronoid disease can take the form of non-displaced and displaced osteochondral fragments, as well as osteochondromalacia. Because plain radiographs are not good at detecting the primary lesion, when using plain radiography, the clinician must rely upon secondary changes, such as subtrochlear sclerosis and osteophytosis.

In addition, secondary changes can be slow to appear in some dogs and plain radiographs may be within normal limits, even in the face of confirmed MCD as diagnosed by CT or arthroscopy2.

Nevertheless, accepting less than perfect specificity and sensitivity, plain radiographs can often be of use in identifying that an elbow joint is pathologic3, although advanced imaging may be required for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

On plain radiographs, the two main features to carefully look for are osteophytosis and subtrochlear sclerosis.

On a mediolateral projection, osteophytosis of the elbow joint will typically be first apparent on the proximal border of the anconeal process (Figure 6) or the cranial aspect of the radial head. Early osteophytes can be small, so careful evaluation of these areas is critical. The proximal border of the anconeal process should be concave and smooth; any convexity indicates osteophytosis. Subtrochlear sclerosis is more subjective. A normal elbow should have a trabecular pattern to the bone in the subtrochlear area and no narrowing of the medullary canal of the ulna should be apparent.

Sclerosis causes a loss of the trabecular pattern and a narrowing of the apparent medullary canal (Figure 6). Humeral intracondylar fissure (HIF; also known as IOHC) is another relatively common condition of the canine elbow joint – particularly in spaniel breeds. Humeral intracondylar fissure is most common in springer spaniels and it can cause chronic lameness.

Diagnosis by plain radiography is not always possible, but the lesion can sometimes be seen on a craniocaudal projection (Figure 7). However, unless the x-ray beam passes along the line of the fissure, the lesion may be missed. CT is the best modality to confirm the diagnosis.

The carpus is a complex three-level hinge joint with most of the movement at the antebrachiocarpal joint.

Pathology of the carpus is less common and the most frequent disorders are of the soft tissue structures which support the carpus, such as the collateral ligaments and the palmar ligament.

Failure of these structures results in instability and, often, this may necessitate some degree of carpal arthrodesis as a treatment strategy. Therefore, standard dorsopalmar and mediolateral views are often complemented by “stress” radiographs, whereby the suspect injured soft tissue structures are placed under mechanical load to see if joint instability is demonstrable.

In the case of palmar ligament rupture, careful evaluation of such radiographs is necessary because, if possible, and in the author’s opinion, if the antebrachiocarpal joint can be preserved, this is preferable for long-term outcome (Figure 8).

Plain radiography has its limitations, but careful technique and interpretation can maximise the diagnostic yield from the modality.

Colleagues are encouraged to see expert opinions on radiographs if they lack confidence or knowledge in specific cases.

Such reports can gradually provide further confidence and knowledge to less experienced colleagues.