29 May 2017

Debbie Gow and Hilary Jackson discuss the options available for using these types of therapies, including the various protocols and side effects.

Figure 1. A dog receiving sublingual immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy has been successfully used for many years as a specific treatment for companion animals diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (AD). The indications, mechanism and outcomes were discussed in part one of this article (VT47.13).

Traditionally, immunotherapy has been delivered using injectable therapy (allergen-specific immunotherapy; ASIT) whereby animals are administered an injection every three to four weeks during the maintenance protocol. An alternative method of delivery is to use sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT), which is becoming increasingly popular with vets and clients as a safe and effective alternative to injectable ASIT.

Reports have been published about using ASIT and SLIT in “rush” protocols, with the aim of achieving the maintenance dose faster and, therefore, alleviating clinical signs more quickly. Ultimately, the protocol used will depend on factors such as the owner’s preference, the temperament of the animal and the facilities available. The exact protocol must always be tailored to each animal, taking into consideration the clinical signs and history, combined with intradermal testing results or IgE serology.

This article will discuss the different options available; however, due to the large variation in protocols available, no specific regime will be discussed in detail. These readers are directed to their immunotherapy provider.

At present, immunotherapy can be delivered routinely by either SC injection or sublingual spray (Figure 1). An area of research is using intralymphatic immunotherapy (ILIT) delivery, which may be a future option. Initial data suggests using this method of delivery will achieve a faster clinical improvement with the same response rate (60%; Fischer et al, 2016).

For ASIT, the most commonly used formulation in the UK is alum-precipitated allergens. Aqueous solution is also available; since allergens are more rapidly absorbed this usually requires more frequent dosing (every two to three weeks of maintenance). For SLIT, the allergens are mixed with glycerol. This is required for stability of allergens, to increase persistence in oral cavity and improved absorption across mucus membranes. The sweet taste increases palatability.

Many injection protocols exist with no standardisation; suggested protocols from allergen supply companies must be tailored to the individual animal. Modification may be required, for example, if pruritus develops a few days prior to the scheduled injection, the frequency will need to be decreased or if pruritus develops after injection, the dose may need to be reduced.

In the UK, no veterinary immunotherapy products have marketing authorisation; therefore, the cascade must be followed. A VMD certificate must be obtained by the veterinary surgeon prescribing the immunotherapy. This may either be a special import licence (SIL) or a special treatment licence (STC) depending on the product/company supplying the immunotherapy.

The majority of canine patients diagnosed with AD will have a hypersensitivity to multiple allergens, thus will require a mixture of allergens to be included in their immunotherapy. The number of allergens included in the immunotherapy will be partly guided by intradermal testing or IgE serology results.

Studies that have examined the effect of allergens on efficacy of treatment have recorded variable results, but, traditionally, no more than 10 are generally used. As a general rule, in animals with more than 10 potential allergens, these should be prioritised based on history, the presence of allergen in the animal’s environment and the seasonal duration of the allergen’s presence (Olivry et al, 2010). The number of allergens to be included may also be reduced by taking into consideration the potential cross-reactivity with other allergens. However, data on this in companion animals is sparse and the authors generally extrapolate from knowledge of human allergen cross-reactivity.

For ASIT, it is recommended mould allergens are separated from other allergens in the dispensing bottles due to proteases released by mould that may degrade other allergens. The contents of the separate vials are mixed at the time of injection so multiple injections are avoided. Using 50% glycerine as a stabilising agent in SLIT will prevent this degradation. Allergens themselves will degrade over time and it is recommended the immunotherapy not be used beyond its expiry date.

It is generally the case the dose of allergens in SLIT would need to be increased compared to injectable ASIT. The concentration of allergens in SLIT is 20,000 protein nitrogen units (PNU) compared to 10,000 PNU in the injectable solution.

In general, ASIT regimes can be divided into an induction and a maintenance phase. During induction, the concentration of allergen administered is slowly increased to the full dose, which will then be given at regular intervals. This reduces the risk of an anaphylactic reaction. Once the maintenance phase has been reached, the full dose of the allergen mixture is given at regular intervals.

Where owners are administering immunotherapy to patients at home, they are advised to remain with their animal 30 minutes to 1 hour after administration and to do this during “normal vet hours” where possible. In the case of patients receiving injections by the owner at home, it is preferred the first four to five injections are administered in the practice. This serves not only to help train and educate the owner in safe and effective injection technique, but also allows the patients to be assessed for any adverse reactions.

In the UK, SC immunotherapy generally refers to aqueous or alum-precipitated formulations. No standardised protocol exists, but, in general, the alum-precipitated formulation is given less frequently, usually on a monthly basis. It should be noted the dose and frequency of administration of allergen recommended by the provider may not be the one best suited for each animal and modifying the regime on an individual basis is not uncommon.

In human medicine, SLIT was developed to facilitate ease of administration and improve the safety of administering immunotherapy to patients with allergic disease, and has been used as a treatment for more than 50 years.

SLIT is used in human medicine for the treatment of allergic rhinitis, asthma, atopic dermatitis and certain food allergies. As with ASIT, SLIT can also reduce the progression of allergic disease. The AD treatment guidelines from the International Committee on Allergic Disease of Animals (ICADA; Olivry et al, 2015) incorporates and acknowledges the use of SLIT as treatment for canine AD as a safe and effective treatment.

SLIT needs to be given twice daily and delivered into the oral mucosa with a pump mechanism. It should not be swallowed and is designed to be absorbed in the oral cavity. A small pilot study suggested an additional benefit of using SLIT therapy may be for dogs diagnosed with adverse food hypersensitivity where SLIT may help reduce pruritus and clinical signs associated with the disease (Maina and Cox, 2016).

Similar to ASIT injections, the aim of SLIT is to induce “immunologic tolerance” and the exact mechanism is unclear, but it is thought to include the induction of regulatory T-cells and IL-10. The oral mucosa, rich in dendritic cells, mediate antigen presentation to T-cells, inducing an effector response. Studies have shown improvement in clinical response was associated with high IgG levels, as in the case for dogs treated with ASIT (DeBoer et al, 2016).

It may also be considered SLIT is a different therapy altogether compared to ASIT, since apparent ASIT failures have shown to respond positively to SLIT, suggesting a different mechanism may be involved. This is also supported by the addition of using SLIT or oral immunotherapy in tablet form to successfully help children with peanut allergy when traditional injection ASIT is not effective.

The potential adverse effects are similar to those reported for injectable immunotherapy (see part one). Dogs that have suffered anaphylactic reactions in response to injectable ASIT appear to tolerate sublingual therapy without such reaction occurring. This is also the case in human therapy.

In the authors’ experience, side effects are uncommon, but include facial pruritus, localised oedema of the lips and face, vomiting and worsening of pruritus (Figure 2). Unpublished data from Heska Corporation (http://bit.ly/2re0Hvk) reports a 4% adverse reaction rate in dogs administered SLIT, with the most common reaction being the worsening of pruritus in 3.1% of dogs followed by gastrointestinal upset in 0.4%. As with injectable ASIT administration, regimes can be modified to ameliorate these reactions.

Since the clinical improvement of AD can take several months, the development of a “rush” protocol was developed in human medicine with the aim of achieving control of clinical signs more rapidly. This rush, or fast track, protocol generally involves giving the total induction course across one day (aqueous injections) or across 48 hours (sublingual). It has been used successfully and safely in human medicine, and also in canine and feline patients (Fujimura and Ishimaru, 2016; Mueller and Bettenay, 2001; Trimmer et al, 2005).

The use of the rush protocol appears to induce similar side effects noted with the traditional method of delivery (increase in pruritus), but not at any increase in frequency compared to the standard method. In veterinary medicine no data exists to determine if using the rush protocol does indeed provide more rapid resolution or improvement in clinical signs.

It does, however, offer a safe and potentially more convenient protocol for dogs starting immunotherapy. As a greater potential for an anaphylactic reaction exists, this type of protocol should only be undertaken with specialist input in a clinic where constant monitoring of the patient is available. Patients require the placement of an IV catheter, access to oxygen, intubation equipment and emergency drugs (Figure 3).

Initially, SLIT therapy in humans was used primarily to treat allergic respiratory disease, but has also been used extensively to treat human AD. The sublingual route appears to be safe and is being used at a similar rate as injections. Limited published data exists for the use of this delivery method in companion animals; however, evidence and consensus of opinion among dermatologists is it is a safe and effective method of delivery (DeBoer and Morris, 2012; DeBoer et al, 2010; Olivry et al, 2015).

At present, only a few published studies use SLIT in canine AD as an alternative to ASIT. The evidence demonstrated 60% to 80% of dogs included in open clinical trials using SLIT had shown clinical improvement that also correlated with a reduction in the glucocorticoid therapy, Canine Atopic Dermatitis Extent and Severity Index score and pruritus (DeBoer and Morris, 2012; DeBoer et al, 2016).

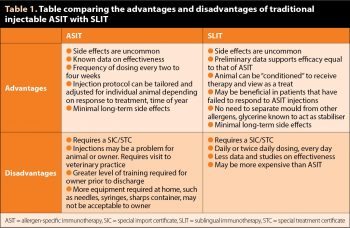

Table 1 details the main advantages and disadvantages of ASIT and SLIT. Both ASIT and SLIT can be used with concurrent medication to control AD, as was discussed in part one. Anecdotal reports suggest dogs may respond quicker to SLIT than ASIT, with clinical improvement noted within 2 to 3 months rather than 9 to 12 months. Further studies are required to determine if this is the case.

A full evaluation of the clinical benefit of ASIT or SLIT should not be made until a full year of treatment has been achieved; however, the authors recommend regular assessment of the animals every two to three months during this initial period. In most cases, where successful, immunotherapy will need to be continued for the rest of the animal’s life; however, reduction in the injection frequency and dose or oral dose frequency can be attempted in cases that are stable with complete remission of clinical signs. ASIT may also be stopped in these cases, if deemed appropriate. Apparent ASIT failures may benefit from receiving SLIT instead of injectable ASIT.

Subsequent follow-up examinations of an animal on immunotherapy will depend to some degree on the animal, the protocol, the severity of disease and the owner. For animals on the maintenance dose and clinically stable, a review every six months is indicated. Owners should be aware of the need to make contact if anything changes, and phone numbers and email addresses provided to clients so they can make contact for advice, if required.

Educating owners about “flare factors” is important to help eliminate or reduce these. Flare factors, if unnoticed, contribute to an apparent failure of ASIT. Depending on the protocol and immunotherapy used, some companies have a reorder period of up to three to four weeks, so owners should be advised of this to ensure they ask for further supplies in good time with no break in ASIT protocol.

Both ASIT injections and SLIT therapy offer safe and effective therapies to manage dogs with AD. Both therapies have excellent safety record for long-term and initial short-term use. Advantages and disadvantages are present for each method and evidence suggests they are different treatments based on the success of SLIT in ASIT injection failure dogs.

Many protocols exist for their use and further work needs to be performed to compare ASIT with SLIT therapy. The decision to start a patient on either therapy is often decided in consultation with the owner, based on the animal’s temperament and anticipated reaction to injection or sublingual therapy, and also by the owner’s lifestyle. The ease of administration and safety of SLIT makes this a very favourable therapy for canine AD.