11 Mar 2019

Yaiza Forcada and Stijn Niessen use research data and real world examples to assess how telemedicine can give a direct line to specialists.

Much of the discussion surrounding telemedicine has focused on how to regulate a consultation between pet owner and vet, since it does not involve the physical presence of a clinician, thus a physical examination with a patient that inherently cannot voice its concerns.

Will we soon be trying to diagnose the cause of Fluffy’s limp or ocular discharge using smartphone cameras? The jury is out, and only time will tell whether the veterinary profession follows human medicine in this regard.

Nevertheless, telemedicine has more to offer than setting up Skype sessions with Fluffy and his owner to discuss why he is suffering from diarrhoea. It is easy to forget telemedicine is as old as the invention of the telephone. For years we have been discussing cases between each other over the telephone. This has enabled additional case input from colleagues, specialists or experts, when those were not physically present in the clinic.

Moreover, teleradiology has been groundbreaking in vet-to-vet telemedicine as one of the first specialisms to routinely and structurally offer specialist input from a distance. Where previously we were putting radiographs in big envelopes, we are able to automatically send extensive image data files seamlessly from our local x-ray machine to a remote radiologist for rapid assessment. Teleclinical pathology should also be seen as early forms of this type of telemedicine.

While vet-to-pet telemedicine is still finding its way, vet-to-vet telemedicine has been developing, professionalising and diversifying in recent years. Traditional forms of vet-to-vet advice services have tended to be a favour from the local specialist, expert or vet school. Time pressure and the sheer volume of the demand has stimulated the creation of professional, independent, fast and reliable services offering the possibility of “real-time” case guidance.

Improved and diversified communication technologies have really helped in this process. When we combine the arrival of these services with a seemingly unprecedented job satisfaction and stress crisis in our profession, it seems only logical to explore how vet-to-vet telemedicine could impact our profession in years to come.

This article will, therefore, focus on how vet-to-vet telemedicine can improve clinical outcomes of patients and their owners. It will also, more importantly, focus on how it can create a support system for veterinary clinicians on a day-to-day basis. The latter seems very timely given that increased pressures from clients and employers, as well as from us clinicians, have been fuelling a veterinary job satisfaction crisis frequently covered in media, studies and literature.

A rurally located colleague vet in a “one-woman practice” was confronted with the arrival of a prize-winning sled dog – a 9-year-old Alaskan husky bitch suspected to be 63 days pregnant. The owners observed straining and clear discharge at 3am that morning, but, despite strong efforts from the bitch, no fetus was delivered. The dog subsequently calmed down again and straining stopped.

The vet reported: “I have to admit I really don’t like these cases because I always feel inadequately equipped to deal with them [in terms of time, drugs and manpower] and I’m out of my comfort zone every time. I find it hard to determine a straightforward protocol, to decide when to wait, how long to wait, when to try oxytocin and when to do a caesarean; most of my clients do not want to, or cannot be, referred elsewhere, so here I am on my own.”

She contacted a telemedicine provider and spoke directly to a board-certified specialist well-versed in the ins and outs of these stressful situations. A video link was quickly established via the vet’s smartphone, which enabled the specialist to see the patient, double-check the dose and formulation of the medications used, look at the abdominal radiographs with her, and, probably most importantly, helped make the vet feel supported, not alone and less stressful.

The specialist helped establish that the pups were ready to be born on the basis of timing, skeletal maturity and size on radiographs, as well as the early signs of partum shown.

It was agreed to determine blood calcium concentration and, if low, to supplement accordingly at the right rate and concentration. The blood calcium turned out to be normal, thus oxytocin administration was advised at a low dose – in fact lower than stated in many formularies – given that excessive myometrial contractions have been shown to excessively compromise pup heart rates.

Another 20 minutes later, the specialist and local practitioner together decided, in the absence of a progression of the labour, a C-section was an appropriate course of action. Seven beautiful healthy pups, a healthy mum (Figures 1 and 2), happy owners and a very relieved local vet were the result.

The past 20 years has seen an increased diversification of veterinary clinical medicine options, with a tremendous increase in the number of veterinary specialists and specialist referral centres. This increased specialisation has allowed state-of-the-art care to be provided to pets around the world – a fantastic development in veterinary care.

Despite the indisputable benefits of specialist care at a referral practice, this option is not available to, or appropriate for, all patients and situations. The case mentioned is a good example of this – the patient was remotely located, the owner did not wish to travel and funds were not available for referral. The local vet was capable of dealing with the situation, but required support, advice and encouragement to get the best result for the patient.

The outcome was good for the patient, but also, importantly, for the vet. This type of supported primary care scenario can give a confidence boost to vets dealing with patients, teach them new ideas or skills and generally improve their job satisfaction.

A delicate balance can clearly be struck between the roles of referral practice, remote specialist support and the primary care vet. These lines will be drawn up over time, just as they have in human medicine. The hope is all three areas can work collaboratively to deliver excellence in patient care for all scenarios and budgets.

Remote specialist support might help to quickly triage situations and identify candidates needing early referral to a hospital, thereby saving valuable time, enabling optimal use of owner funds, and resulting in a better clinical outcome. Organised services providing remote specialist support could reduce strain on a referral centre, enabling the specialist to spend more time with his or her patients, rather than on the telephone.

Recent work reveals we do have a problem with job satisfaction, well-being and staff retention in our profession. Examples include one survey indicating only 24% of graduates under the age of 35 would recommend their profession to friends and family. By contrast, in the general population, younger adults were more likely (82%) to recommend their career (Volk et al, 2018).

Other examples report on the extraordinarily high suicidal tendency in our profession (one in six in some studies), five times national averages (Nett et al, 2015). Causes will be multifactorial. Creating better support structures, ensuring no one feels alone, out of depth or not cared for could help. Accessing support from colleagues through telemedicine could be one of the means.

A telemedicine trial (May to June 2018, VetCT Telemedicine Hospital study, unpublished data) involved providing 17 UK small animal practices with 42 clinicians with various degrees of experience unlimited real-time access to a team of remotely located, board-certified specialists for 6 weeks.

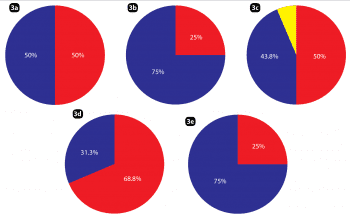

The impact of having this instant specialist support network available through their telephones, a messaging application for smartphones, emails, and a dedicated web platform was assessed via survey. Among the results, a positive impact was reported in terms of confidence, stress levels, ability to deal with cases in-house and the development of new skills realised through case-by-case interactions with veterinary specialists (Figures 3a to 3e).

After the trial, individuals also commented on the benefit of having an independent colleague, who is not part of the practice team, available to talk cases through with, but to also share a difficult day or bad experience with; therefore, supplementing the support structure already present in the physical environment of the practice.

Historically, vet schools and multidisciplinary referral hospitals have been heralded as the places to be to find an environment where mentorship is taken seriously and gold standard medicine is practised. Since most vets do not practise in such environments and most pets (VetCompass data: 98%) do not get referred for a variety of reasons, specialist-led telemedicine could provide the opportunity for any practice, large or small, rural or urban, to surround itself with a support structure and mentorship scheme.

Another trend has been a gradual decline in the numbers of experienced senior partners within a veterinary practice on a day-to-day basis. This trend may be, in part, due to progressive corporatisation, and, in part, due to a shift back to smaller veterinary practices with only one to two vets present on site. In the past, the senior partner frequently acted as a role model and mentor for younger vets; therefore, a support void exists in some practice environments.

The mentoring role provided by a vet-to-vet telemedicine service can increasingly be enhanced through various technical advances.

Video links established through a smartphone or webcam allow the supervision of procedures by specialists, including abdominal ultrasound, echocardiography and ophthalmic examination. Images from a microscope can travel the world in seconds to land on the desk of an internist or clinical pathologist, and sharing of audio data from digital stethoscopes enables a remote cardiologist to listen to the same heart murmur as the local practitioner.

Since the beginning of 2018, the Vet CPD Telemedicine Hospital has been helping vets place SC glucose monitors through a video link (Figure 4); the continuous glucose monitors allow minute-by-minute at-home recordings of SC glucose in diabetic pets over a period of two weeks, without the need for any blood sampling. The glucose readings can be sent by the owner to the practitioner or by the practitioner to the specialist for further interpretation. Placement of the monitors is safe, but can prove tricky without prior experience, although remote guidance by an expert makes this much more feasible.

Remote guidance can be used for many other procedures, such as ophthalmic examination (Figure 5). Even more complex and invasive techniques, such as acquiring a bone marrow sample, can be facilitated with remote guidance as long as careful consideration is given to risks.

While vet-to-pet telemedicine continues to be mired in controversy, vet-to-vet telemedicine already offers great opportunities to improve the care of animals that would normally not benefit from repeated specialist input.

One of the most important dimensions in which telemedicine could create real positive change is in mentorship. Opportunities exist for clinicians young and old; nurturing younger vets and reducing their stress levels, while building their own clinical comfort zone; and stimulating colleagues more established in their careers who might feel stuck in a rut.

Telemedicine is not here to replace or challenge referral through the use of gadgets, but to provide a third way of practising that is available in addition to referral and local services. A third way where we integrate the input of specialists into daily practice as a means of investing in ever-better clinical care and, above all, continuing development and mentorship for ourselves. The gadgets do help, though.