17 Oct 2023

Richard Morris discusses the difficulties of deciding on the best treatment to halt the issue of – and reduce pain in – aural disease.

Ear disease is a common problem in general practice and deciding on the most appropriate treatment to halt the disease and reduce pain and discomfort can be challenging.

The signs of otitis include head shaking, self-trauma, a bad odour from the ear, inflammation of the ear canal, an excessive exudate and areas of acute moist dermatitis (hot spots) on the head and neck.

Chronic otitis is often a manifestation of a dermatological process, and the epithelial lining of the ear canal is an extension of the skin of the head and neck. The causes of otitis can be categorised into predisposing, primary, secondary and perpetuating causes (Table 1; Griffin, 2010), which allows for a better understanding of the causative factors in a particular case and more effective treatment.

| Table 1. Primary, secondary, predisposing and perpetuating factors for otitis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Aetiology | Examples | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Primary factors | These affect a normal ear and are directly responsible for otitis |

Parasites – ear mites, Otodectes cynotis Hypersensitivity disorders (atopy, food allergy) Foreign bodies Keratinisation disorders autoimmune disorders (vasculitis, pemphigus foliaceous) Endocrine disease – (hyperadrenocorticism, hypothyroidism) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secondary factors | These are secondary infections as a result of otitis caused by primary factors | Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Malassezia species | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predisposing factors | These factors increase the risk of otitis developing, but are not responsible for causing ear problems; for example, breed-associated conformation problems |

Anatomical conformation – pendulous pinna (spaniel), narrow ear canal (Shar Pei), hirsute canal (poodle) Excessive cerumen production Polyps or tumours developing Excessive moisture – swimming Inappropriate medication – bacterial resistance, contact, hypersensitivity, aggressive cleaning |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Perpetuating factors | These factors are the result of chronic changes to the anatomy and physiology of the ear canal. They allow the condition to continue and, unless addressed, the problem will not resolve |

Inadequate epithelial migration, hyperplasia/fibrosis/calcification of the canal wall Tympanic abnormality – choleasteatoma Otitis media |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Identifying an underlying cause and initial medical treatment can often resolve the ear disease, but unfortunately, a number of cases will progress and need surgery. Identifying the contribution of dermatological conditions to the disease and choosing the right surgical approach is essential before embarking on surgery in order to ensure a good outcome.

History taking is an essential part of understanding the aetiology of each individual case of otitis and the age of onset is often helpful in determining the primary cause of inflammation (Forsythe, 2016). For example, atopic dermatitis is seen in younger dogs, whereas endocrine disorders or neoplasia is often seen in older individuals and neoplastic otitis is often unilateral (Paterson, 2016).

Otoscopy is important to categorise the state of the ear canals into either erythroceruminous or suppurative otitis based on type and amount of discharge, and also to assess the integrity of the tympanic membrane (Nuttall, 2016). Erythroceruminous otitis presents with pruritus, erythema and a ceruminous seborrhoeic discharge, and is usually associated with staphylococcal or Malassezia overgrowth. Suppurative otitis presents with erythema, ulceration and pain and is more often associated with a Pseudomonas infection. Cytology of the exudate found on otoscopy can help identify the presence of Otodectes (Figure 1) Staphylococcus, Malassezia (Figure 2) or Pseudomonas species (Figure 3).

Pre-surgical assessment involves palpation, otoscopy, cytology of the exudate, neurological examination, bacterial culture and radiography. Radiography with a rostro-caudal (open mouth) and dorsoventral view of the head are the most helpful views for looking for loss of air density within the tympanic cavity, indicating otitis media or a tumour (Figure 4), and ossification of the cartilages of the ear canal (Figure 5).

CT scanning is the optimal technique for examining the middle ear, and MRI is sensitive for examining the inner ear and adjacent structures (Benigni and Lamb, 2006), but often information from the history, clinical examination, and x-rays is insufficient to decide on the most appropriate treatment approach.

If the underlying causes can be identified and treated, it may be possible to resolve the problem with medical treatment alone; however, in some cases, perpetuating factors prevent the problem resolving and the disease becomes chronic. Ear canal stenosis, tympanic membrane perforation and otitis media were found to be the most important perpetuating factors in dogs (Saridomichelakis et al, 2007).

Otitis media is the single most important factor attributed to treatment failure leading to persistent head shaking and otorhoea (Lane and Little, 1986) which, if not diagnosed and treated, leads to a lack of response to therapy (Paterson, 2016).

Predisposing factors such as tumours of the external ear canal and tympanic bulla (Little et al, 1986), cholesteatomas in the cat and the dog (Alexander et al, 2019; Riedinger et al, 2012), and primary secretory otitis media of the cavalier King Charles spaniel (Stern-Bertholtz et al, 2003) will progress to chronic otitis unless addressed.

Electrocautery or laser surgery can be used to remove some tumours (Bentley, 2022; Aslan et al, 2021) – particularly ceruminous gland hyperplasia in cats (Corriveau, 2012; Figure 6).

If the cycle of recurrent inflammation, chronic infection and progressive pathological changes are not resolved, end-stage otitis develops requiring surgical intervention (Nuttall, 2016). The role of surgery is to remove infected tissue and improve the ventilation of the ear canal; the most appropriate technique depends on the degree of ear disease and three surgical approaches have been described: the lateral wall resection (LWR), vertical canal resection (VCR) and the total ear canal ablation and bulla osteotomy (TECA BO; Table 2).

| Table 2. Surgery for chronic otitis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technique | Purpose | Application | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lateral wall resection (LWR) |

Improve aeration of the aural microclimate and improve drainage of the horizontal canal |

Congenital canal stenosis Small tumours of the tragus or lateral wall of the vertical canal To facilitate medical treatment where reversible skin changes in otitis externa are seen |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vertical ear canal resection | Excise the upper portion of the external meatus where irreversible changes have occurred |

When the vertical canal is diseased but the horizontal canal is unaffected Hyperplastic otitis Ear trauma Ear tumours limited to the vertical canal |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total ear canal ablation | Resolve otitis media and treat irreversible changes of the ear canal where there is a deficient horizontal canal |

Ceruminous gland adenocarcinomas; failed LWR or vertical canal ablation Extensive benign disease Extension of disease into the middle ear cavity |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The approach for all three operations is the same: the anaesthetised animal is placed in lateral recumbency with the affected ear uppermost, a towel placed under the neck will raise and increase the exposure of the ear, the hair is clipped from the neck to the maxilla, scrubbed with dilute chlorhexidine, and then sprayed with surgical spirit. A probe inserted into the vertical canal gives a good indication of the course of the vertical canal and where the horizontal canal begins, allowing the surgeon to map out the lines of incision.

Pain relief is important, as these are painful procedures. The author administers preoperative and postoperative opiate injections alongside a course of a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication. Appropriate antibiotic cover is essential before, during and after surgery to minimise postoperative infection and wound dehiscence, preferably based on culture and sensitivity results.

An LWR is appropriate for reversible otitis externa or small lateral wall tumours of the vertical canal, and involves cutting away the lateral half of the wall of the vertical canal so the horizontal canal opens out directly on to the side of the head, with a baffle plate created for drainage.

The construction of a baffle plate was first described by Zepp in 1949 and allows for increased drainage of the horizontal canal. This procedure is useful for early cases of otitis where increased ventilation and improved drainage can prevent the otitis becoming chronic (Figure 7 and Figure 8), but is not appropriate for cases where there is a disease of the medial wall of the vertical canal or the horizontal canal.

A 34% to 47% failure rate has been documented (Mason et al, 1988) going up to 86.5% in cocker spaniels (Sylvestre, 1998) due to ongoing otitis because primary causes have not been addressed, unrecognised otitis media perpetuating the problem, or poor drainage due to an inadequate drain plate.

If the outcome has been disappointing, revision surgery by carrying out a VCA can be carried out provided no evidence exists of otitis media and the horizontal canal is normal, alternatively a TECA and bulla osteotomy can be performed.

Vertical canal ablation (VCA) is a procedure suitable for cases of severe vertical canal disease where the horizontal canal is normal, removal of the vertical canal in the VCA allows for improved ear ventilation and drainage for early cases of otitis where the vertical canal is diseased, but the horizontal canal is healthy.

Two techniques are described; both involve a circumferential incision around the external acoustic meatus and cutting through the base of the auricular cartilage. In the original approach (Lane, 1979), a vertical incision is made over the external vertical canal and the conchal cartilage trimmed away from the head and severed at the level of the horizontal canal, a baffle plate is created, the dead space sutured and the incision closed (Figure 9).

An alternative approach described by Tirgari and Pinniger (1986) which results in less trauma and postoperative discomfort avoids making a vertical incision. A circumferential incision is made around the external acoustic meatus and the vertical canal is trimmed away from the subcutaneous tissue without making a vertical skin incision. A separate circular incision is made at the level of the horizontal canal about one and a half times the diameter of the horizontal canal and the vertical canal is pulled through the circular hole, severed at the base and sutured to the skin margin of the hole. In both cases, it is important to prepare a drainage plate similar to the lateral wall resection.

So long as underlying primary factors are addressed, the outcome is good, but in poorly managed long-term diseases such as hypersensitivity disorders, continued otitis of the horizontal canal will result in chronic skin changes in the remaining skin of the ear (Figure 10).

The TECA BO is an end-stage procedure to resolve advanced disease of the ear canal or otitis media, and improve the quality of life for an animal with a chronically diseased ear. It is a high-risk procedure that should only be carried out by surgeons experienced in ear surgery and after counselling the client of the risks.

Postoperative complications arise in about 29% of dogs and include facial nerve injury, inner ear injury, haemorrhage (from the caudal auricular artery, superficial temporal artery or retroglenoid vein) and wound dehiscence (White and Pomeroy, 1990). Also, facial nerve paralysis, pain in the temporo-mandibular joint, Horner’s syndrome, vestibular syndrome, swelling, recurrent infection, pinna necrosis and compromised movement can occur. About two-thirds of cases have an excellent recovery (Mason et al, 1988); those that develop complications can be difficult to treat (Smeak et al, 1996). In some cases, this may be just due to infection or retained epithelium and debris; however, facial nerve paresis can occur in 27.1% of cases and paralysis in 21.8%, and can take two to four weeks to resolve (Spivack et al, 2013). In cats, the risk of postoperative complications is higher with 42% of cases having Horner’s syndrome and 56% suffering facial nerve paralysis; a proportion recovered over the following weeks, but 14% and 28%, respectively, were left permanently damaged (Bacon et al, 2003).

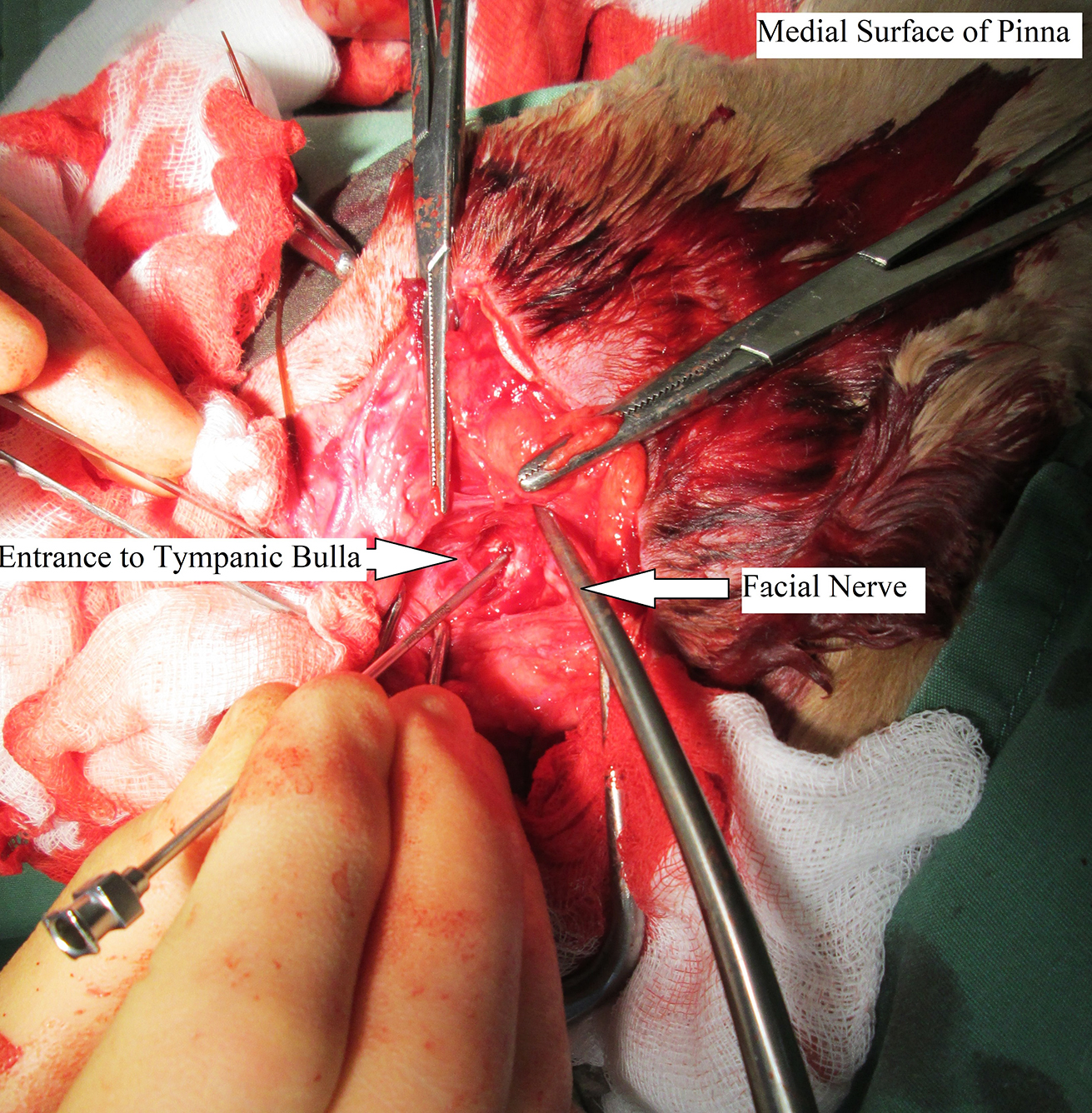

In both cats and dogs, the approach for a TECA is the same: a probe is inserted in the vertical canal and the skin incised over the probe from the external acoustic meatus to the level of the horizontal canal. A horizontal incision is then made at the top of the vertical incision and extended round the top of the external auditory meatus and to the base of the pinna cutting through the auricular cartilage. The soft tissue is then dissected around the vertical and horizontal canal to release the external ear from the surrounding musculature and lift it away from the head, taking care not to damage the facial nerve; the complete vertical and horizontal ear canal can then be severed at the level of the tympanum and removed.

It is important not to dissect too deeply around the ventral aspect of the tympanic bulla, as this is where the facial nerve and external carotid artery lie, and damaging these structures should be avoided.

In dogs, otitis media is usually an extension of otitis externa and the operation proceeds to a lateral bulla osteotomy. The ventrolateral surface of the tympanic bulla is removed with rongeurs to allow access for a small curette to scrape away the epithelial lining of the tympanic bulla, being careful to avoid the round window (mid-dorsal aspect) or oval window (craniodorsal aspect).

Some surgeons remove most of the lateral and ventral wall of the bulla to decrease the risk of para-aural abscessation, but a keyhole LBO can be carried out (Charlesworth, 2012) where the entrance to the bulla is widened sufficiently to allow curettage and flushing of the bulla but involves less trauma and potentially fewer complications. This is the technique used by the author (Figure 11) and provided the epithelial lining of the bulla is completely removed and any remaining debris thoroughly flushed away with saline, the chances of postoperative abscessation are reduced.

In the cat, a ventral bulla osteotomy is the more routine approach, as otitis media is often seen without involvement of the external ear. The surgery is relatively straightforward because the ventral surface of the tympanic bulla is easier to identify. A drill or Steinmann pin is used to create a ventral opening in the tympanic bulla for curettage and flushing; this provides better access to the tympanic cavity and a reduced risk of facial nerve injury.

In the cat, the tympanic bulla is divided into a smaller dorsolateral and larger ventromedial chamber by an incomplete bony septum. Care should be taken to minimise iatrogenic damage to the medial surface of the tympanic bulla where the round window of the cochlea and post-ganglionic fibres of the cervical sympathetic trunk lie. Damage to these structures leads to Horner’s syndrome, which arose in 57% of cases in one study (Adler and Booth, 1979).

In the dog, a ventral approach is more difficult and requires patient repositioning after the TECA has been performed and shown not to provide any advantage compared to a lateral approach (Sharp, 1990). Samples from the middle ear should be sent for bacterial culture and sensitivity, and it is helpful to leave a postoperative drain in place for two to three days when closing the wound to aid the discharge of postoperative fluid and reduce swelling (Devitt et al, 1997).

In some cases, a bilateral TECA and LBO will be necessary; it is recommended to operate on one ear at a time with a three to four-week gap between operations as postoperative pharyngeal swelling may be severe causing the need for a tracheostomy (Smeak and Kerpsack, 1993). Surprisingly, animals do not appear to be deaf after a bilateral TECA and LBO – some sense of hearing remains, possibly via vibrations through the skull.

The successful management of otitis depends on matching the patient with the right procedure and competent surgical technique (Lane and Little, 1986). Managing and treating otitis can be a complicated process, but by taking a methodical approach, identifying and treating the primary factors, resolving the secondary factors and identifying the perpetuating factors, successful management can be achieved.

Making a definitive diagnosis and addressing the cause of the otitis is essential, and attention to detail, gentle tissue handling and good haemostasis are important to minimise the complications of surgery.