26 Aug 2019

Sarah Caney details how to diagnose this common disorder, which predominantly affects older felines.

Figure 1. A poor coat is commonly reported in cats with hyperthyroidism.

Hyperthyroidism – the clinical syndrome resulting from excessive circulating levels of thyroid hormones – is the most common endocrinopathy in cats and especially common in older cats. The median age at diagnosis is usually around 12 to 13 years old.

Clinical signs vary in severity, according to how long the cat has had hyperthyroidism and whether concurrent disease is present. History and physical examination often give clues of hyperthyroidism, but total thyroxine testing is required to confirm the diagnosis.

In most cases, diagnosis is straightforward, but in a small number of cats it can be very challenging, with additional tests/extended thyroid profiles needed to make the diagnosis.

Hyperthyroidism was first reported in the late 1970s and is known to affect around 10% of cats older than 10 years of age. It is unusual to diagnose hyperthyroidism in cats younger than 7 years of age – less than 5% of cases are diagnosed in this age group.

As with all illnesses, a diagnosis is based on history, clinical examination and the results of laboratory tests. The clinical signs of hyperthyroidism vary in severity, and are generally most severe in cats that have been suffering with the illness for longer and cats that have concurrent illnesses.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is one of the most common concurrent illnesses and this results in a worsening of many of the clinical signs.

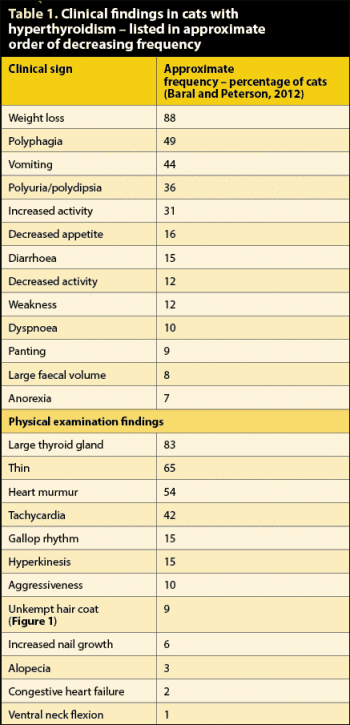

Common clinical signs of hyperthyroidism an owner may notice are listed in Table 1.

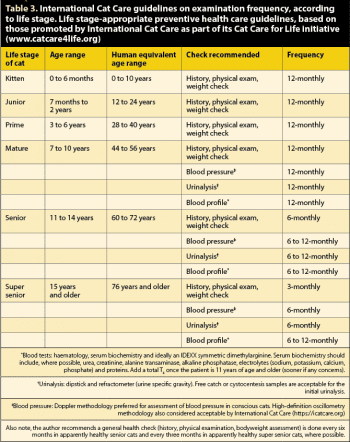

Often, clinical signs develop slowly, which can make it difficult for carers to spot signs of illness in their cat. This is one reason why preventive health care checks are so important in ageing cats – the charity International Cat Care recommends a total thyroxine (T4) test as part of 6-monthly to 12-monthly routine blood tests in cats aged 11 years and older.

Cats showing depression, lethargy and reduced appetite are often referred to as “apathetic” hyperthyroid cases. This has traditionally accounted for less than 10% of all hyperthyroid cats. Some of these cats are overweight, rather than thin. Most apathetic hyperthyroid cats are suffering from severe cardiac complications associated with their hyperthyroidism.

A veterinary clinical examination may find additional abnormalities in a hyperthyroid cat (Table 1). The patient may be difficult to examine through being more anxious or active in the consulting room. Even if weight loss has not been noticed by an owner or care provider, it’s important to check the cat’s weight and body condition score. Many cats are good at “hiding” weight loss, so it is sometimes only evident when they are placed on the scales.

The overwhelming majority of hyperthyroid cats have a palpable goitre. The goitre is usually palpated in the neck, just below the larynx, on one or both sides of the trachea (Figure 2).

The size of the goitre can vary enormously. In most cases, the goitre is not visible by eye and is the size of a garden pea. In rare cases, the goitre can be as large as a golf ball.

The goitre is usually mobile to a certain degree – in other words, it is possible to move it by a few millimetres under the surface of the skin. In most patients, both thyroid lobes are enlarged.

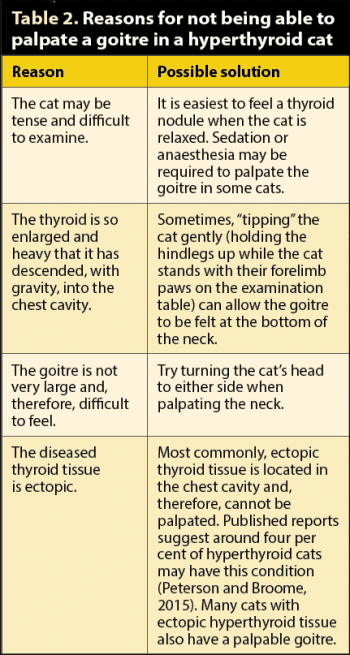

In some cats, more than two areas of enlarged thyroid can be felt due to disease affecting ectopic thyroid tissue. In a small number of hyperthyroid cats, the enlarged thyroid cannot be felt; this may be for several reasons (Table 2).

In the very small number of cats with thyroid adenocarcinomas, the thyroid may feel adherent to underlying tissues and/or the skin.

Occasionally, cats will have a goitre, but not be suffering from hyperthyroidism. This can be because the mass palpated is not thyroid tissue (for example, being parathyroid gland) or if the thyroid mass is non-functional.

Many euthyroid cats with a goitre are suffering from subclinical hyperthyroidism – it is thought most hyperthyroid cats pass through a one-year to three-year period of subclinical hyperthyroidism before developing overt hyperthyroidism.

During this period, the cat has total plasma T4 concentrations within the reference range, in combination with persistently low levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Many of these cats later go on to develop hyperthyroidism, so close monitoring of these patients is justified. For example, this may include a check-up (including bodyweight measurement) every 3 to 6 months and laboratory profiles (haematology, serum biochemistry, total T4) every 6 to 12 months.

Weight loss or development of other signs of overt hyperthyroidism should prompt immediate laboratory investigations.

Hyperthyroidism may be suspected on the basis of the aforementioned historical and clinical findings.

In most cats, the diagnosis can be confirmed by measuring resting serum total T4 levels. Changes found on routine blood profiles include elevated levels of liver enzymes (alanine transaminase and alkaline phosphatase), leukocytosis, eosinopenia and erythrocytosis. Mild hypokalaemia and/or hyperphosphataemia are seen in a small number of patients.

Hyperthyroid cats are reported to be more vulnerable to bacterial lower urinary tract infections; so, where possible, cystocentesis urinalysis and bacteriology is indicated. Urinalysis is also indicated as part of detailed screening for concurrent illnesses, such as CKD and diabetes mellitus (DM).

Although the majority of hyperthyroid patients are easy to diagnose with a single total T4 test, now we are becoming more adept at making this diagnosis, we are seeing more early and “occult” cases that can be difficult to diagnose. For example, in some patients showing clinical signs compatible with hyperthyroidism, a normal total T4 result may be received. Hyperthyroid cats may have total T4 results within the reference range for a number of reasons:

If the total T4 result is in the lower half of the reference range, hyperthyroidism is unlikely. However, if the total T4 result is in the upper half of the reference range, hyperthyroidism remains a potential differential diagnosis. In these patients, a simple and often effective method of confirming the hyperthyroidism is to repeat the total T4 measurement after a few weeks.

Free T4 measured by equilibrium dialysis can be another useful diagnostic tool, in combination with total T4 testing. This test is highly sensitive in diagnosing hyperthyroidism, although a small number of false-positive results can occur – meaning the free T4 test should not be used as a screening test for diagnosis of hyperthyroidism.

An elevated free T4 (greater than 40pmol/L) in addition to total T4 in the upper half of the reference range (greater than 30nmol/L) is consistent with a diagnosis of hyperthyroidism in cats with goitre and compatible clinical signs – especially if they are known to have additional concurrent disease.

Use of the canine TSH (cTSH) assay in cats has received attention in the diagnosis of both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. In patients with subclinical and occult hyperthyroidism, cTSH levels are low or undetectable. Unfortunately, cTSH levels may also be low in a significant proportion of apparently healthy older cats (Peterson et al, 2015), so this test is not recommended on its own as a screening test.

Combining the cTSH with total and free T4 tests can enhance the ability to diagnose hyperthyroidism in tricky cases (Peterson et al, 2015). Also, if cTSH levels are measurable then it is very unlikely your patient is suffering from hyperthyroidism, since only 2% of cats with hyperthyroidism fall into this category (Peterson et al, 2015).

Other options for diagnosis of difficult hyperthyroid cases include dynamic thyroid tests (T3 suppression, TSH/thyrotropin-releasing hormone; TRH stimulation test) and thyroid imaging (scintigraphy).

Dynamic thyroid tests are not always straightforward to interpret and are much less frequently performed nowadays, since they require multiple samples to be collected and may result in side effects (cats injected with TRH commonly vomit post-injection). Scintigraphy requires access to specialist facilities and is not routinely available.

A well-acknowledged side effect of managing hyperthyroidism is the possibility of a clinically significant deterioration in renal function following a return to euthyroidism. This occurs since the hyperthyroid condition increases renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

When the hyperthyroidism is treated, the increased cardiac output and renal blood flow to the kidneys decreases. This results in a decrease in GFR by up to 50 per cent of the pre-treatment level. For many hyperthyroid cats, this return to a euthyroid state is not associated with kidney problems. However, in a proportion of patients, this reduction in blood flow has the potential to unmask kidney disease that was not previously recognised, allowing the pre-existing kidney disease to manifest itself clinically.

The reported frequency of this complication has varied in publications. In one report, a third of patients developed this complication following treatment with radioiodine, while other reports have found even higher numbers of cats experiencing a crisis after treatment.

Affected cats become azotaemic and may start to show clinical signs of renal disease. Significant decreases in renal function are generally evident by four weeks post-treatment, after which time GFR stabilises with very little deterioration, depending on the degree or stage of renal disease.

The IDEXX symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) assay has received interest for its utility in early diagnosis of CKD in cats and now, in identifying cats that are more likely to develop renal complications following stabilisation of their hyperthyroidism.

Peterson et al (2018) showed that while non-azotaemic cats with elevated pre-treatment SDMA were more likely to develop renal complications following stabilisation of their thyroid disease, having a normal pre-treatment SDMA was no guarantee of protection from renal complications. In other words, assessment of pre-treatment SDMA had a poor sensitivity, but high specificity for predicting azotaemia following treatment of hyperthyroidism.

In the author’s experience, hyperthyroidism is still underdiagnosed in practice. Vigilant veterinary attention is essential to diagnose this condition in the early stages. Measures that enhance a prompt diagnosis of hyperthyroidism in all elderly cats include owner education (for example, clinical signs of hyperthyroidism) and following the International Cat Care recommendations for preventive health care checks (Table 3), which include annual urinalysis and blood pressure checks from the age of seven years upwards, and annual total T4 testing from the age of 11 years old.

Weight loss and other signs consistent with hyperthyroidism should not be ignored, but seen as an opportunity to perform further investigations, with the aim of starting appropriate interventions at the earliest opportunity.

Diagnosing hyperthyroidism is often straightforward – especially in cats that have been suffering for some time. Diagnosis of earlier cases can be more demanding, especially if concurrent disease is present. Diagnosis of hyperthyroidism is rarely an emergency as this is a slowly progressive illness. Therefore, if in doubt of the diagnosis, repeat assessment (a “watch and wait” approach) is sensible, rather than treating the cat.