5 Feb 2021

Fernando Freitas DVM, MSc discusses initial steps, examination and treatment for breaks or dislocations of the spine in canine and feline patients.

The spinal cord is the specialised part of the CNS that controls most body movements. A spinal fracture/luxation (SFL) can be devastating since the nervous system is made of very delicate tissue with limited regeneration and multiplication capability.

Damage control on spinal trauma has two fronts: treating the primary and minimising the secondary lesion1.

The primary lesion happens at the time of trauma and depends on the amount of energy that hits the spinal cord2,3, the severity of the compression (if any) and the time this compression operates on the spinal cord4. Among the three factors, the vet can only act in the final one (timing). So spinal trauma must be treated as fast as possible, respecting the priority of the ABCD trauma guideline.

The secondary lesion is a consequence of biochemical activities that perpetuate and worsen the lesion, such as oxygen or lipid free radicals. These factors are responsible for up to 10% of the damage5; however, since small animals need just 5% to 10% of spinal neurons to present a voluntary gait6, simple measures can make great differences in the prognosis1.

Many attempts to find a drug that may assuage this biochemical phenomenon have failed and only one drug showed a very small benefit in humans (high dose of methylprednisolone sodium succinate)7-10, but it failed to show any benefits in small animal patients11.

Steroids may still be used in some multiple trauma patients12, but currently no evidence suggests a benefit when used in high doses for spinal trauma11.

SFL should be initially treated with support treatment to maintain the blood pressure and perfusion towards spinal tissue that may be already presenting hypoxic areas. Additionally, treatment should include immobilisation to avoid worsening of mechanical trauma.

SFL patients that have intact deep pain perception have a prognosis of recovering locomotion similar to disk diseases1 (90%)13,14. However, if the dog or cat loses the deep pain perception due to an SFL, it drops to 12%15, which is much different from the prognosis for disc disease without pain perception (47% to 69%)13,16,17.

Excessive movements, such as postural reactions or full gait analysis, should be replaced with observation of the patient limb movements or mechanical stimulation to predict voluntary movements. A history of pelvic limbs dragging after the trauma or not being able to walk with all four limbs and recumbency are important information as well.

Spinal shock, Schiff-Sherrington syndrome or multiple fractures sites may mask the neurological examination1,18. Giving analgesics after the neurological exam will add just a few minutes between the medication and evaluation1. However, due to the high euthanasia rate of SFL patients without deep pain perception19,20 because of poor prognosis on gait recovery associated with patient home care and faecal/urinary incontinence, a precise predicted prognosis based on pain perception is paramount for the owner’s decision to pursue further treatment.

Radiographs have the sensitivity of 72% for fracture/luxation – especially in the vertebra’s dorsal or middle compartments21. A full radiograph spinal study is recommended and may help, but never replace the neurological exam, to find the accurate lesion localisation and undercover lesions1.

A CT scan is the gold standard for a full assessment of the bone lesion21, and to check for spinal compression secondary to bone fragments or mineralised disc into the vertebral canal19.

In addition, MRI is the gold standard to evaluate spinal cord compression, inflammation, haemorrhages and assess the disc; however, it may not be as useful for bone structure full assessment22. Ideally, both should be considered23, but a CT scan should have priority.

The decision regarding surgical treatment rather than medical should be considered when the animal is paretic, or has a deteriorating neurological status with spinal compression (secondary to bone, mineralised disc or spinal canal deviation) or an unstable spinal column lesion1.

Long-term patient care, including faecal/urinary incontinence, should be taken into account by the owner when deciding to pursue further treatment – especially in animals with no deep pain perception where the surgical procedure is performed to provide comfort for the patient, without an expectation of functional recovery of the limbs1.

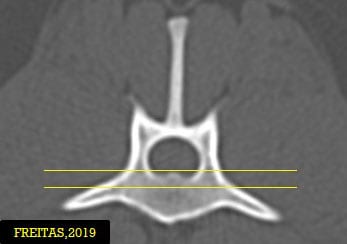

Based on the three compartments theory, a spinal lesion is unstable when two or more compartments are compromised24 (Figure 1). It is the author’s opinion that this theory should be considered – besides, it has never been deeply studied or proven – but the ultimate decision should be individualised case by case together with the owner.

Medical treatment consists of cage rest for four to eight weeks, pain management and patient care (including faecal and bladder management)1,22. Surgical treatment consists of the realignment of the spinal canal; removal of debris, bone fragments or mineralised disk material; and stabilisation. The main component of decompression is achieved through realignment of the spinal canal1.

Since 1971, eight major techniques were described, with some modified later. Currently, no clinical study exists comparing them, so biomechanical studies should be considered when choosing the stabilisation technique.

Pins/screws and bone cement (polymethyl methacrylate) are the most used worldwide and they are the author’s choice due to their good biomechanical properties, material feasibility, low cost and low complication rate (Figures 2 to 4). The major complication is the risk of infection, which is mostly solved with antibiotic treatment and can be added into the bone cement22.

However, in the past few years pedicle screws (the gold standard implant used in humans) are becoming commercially available in smaller sizes (3.5mm and 2.7mm) for the veterinary market and the cost is dropping, which could be game-changing for small animal SFL treatment in the next few years.

Overall, the most important goal of SFL treatment is to stabilise the primary and minimise the secondary lesion. The first one can be achieved by surgical stabilisation or cage rest. Support treatment may help to address the second, but a specific treatment, such as free radical scavengers, is still an unsolved question.