20 Feb 2017

Kelly Bowlt Blacklock in the second of this two-part article, discusses different techniques to close wounds in canine and feline patients.

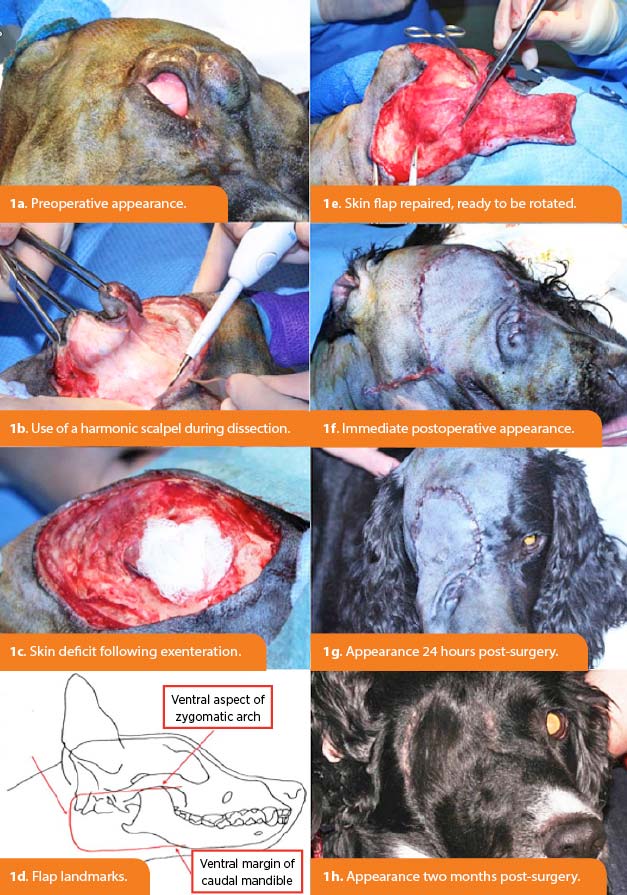

Figure 1. Resection of an intermediate grade soft tissue sarcoma of the right upper eyelid in a spaniel21. Exenteration of the right globe and orbital contents was performed, along with a wide skin excision (3cm lateral margins and a deep fascial place). A complex facial skin flap, involving the inferior and superior labial arteries and the angularis oris artery was raised. As described by Yates et al22, flap landmarks were the ventral aspect of the zygomatic arch, the ventral margin of the caudal mandible and the wing of the atlas (1d and 1e). The flap was rotated and sutured into position, while the donor site was closed primarily and without tension (1f and 1g). Image: AHT.

This two-part article looks at some reported advances in companion animal wound care, with part one (VT47.02) having covered negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT). This second part will look at some of the other topical therapies available and options for wound closure.

Regardless of the treatment used, it is imperative generous, multimodal analgesia should be provided to every patient, discussion of which is outside of the scope of this article. Additionally, clinicians should also be mindful novel treatments are not always superior treatments – evidence-based medicine should be practised wherever possible.

Knotless barbed sutures are available in various sizes and polymers, and contain regular unidirectional or bidirectional barbs that reportedly allow tension to be distributed uniformly across the suture length1. Elimination of knots achieves a reduction in surgical time and foreign material, and barbed sutures have been used in many human tissues1-3.

The author uses barbed sutures regularly to achieve skin closure in companion animals, with excellent cosmetic results, and similar anecdotal information exists from other clinicians. Reported successful use in small animals mainly involves the gastrointestinal tract4-6, although a small number of patients have undergone successful midline coeliotomy closure using barbed sutures7. Cadaveric or in vitro studies have been completed with variable results for conditions such as diaphragmatic herniorrhaphy8, tendon repair9, cystopexy10 and cholecystoduodenostomy11.

Antibacterial-impregnated (for example, triclosan) suture materials are available and are reported to result in an inhibition of bacterial colonisation of the suture, and a reduction in surgical site infections by up to 30% in humans12-14. Unfortunately, a paucity of similar studies exist assessing the use of such sutures in the canine or feline species.

In one study, no significant difference in surgical site infection was seen following tibial-plateau-levelling osteotomy surgery after use of conventional or triclosan-impregnated sutures15, while, in a separate experimental study, use of triclosan-impregnated sutures in patients with established urinary bladder infections resulted in a reduction of the bacterial numbers on and around the suture material, along with improved wound healing16. Larger clinical studies are desperately required to investigate use of barbed and antibacterial-impregnated sutures in veterinary species.

In veterinary species, we are fortunate to have a wealth of local and axial pattern flaps available for closure of skin defects, all of which have been beautifully described elsewhere17.

Several papers have explored less commonly used flaps, or novel flaps entirely, including:

Honey is increasingly used in vet practice. It:

Honey’s antibacterial property is a result of its high osmolarity and acidity (pH 3.6 to 3.7), with manuka honey being uniquely effective in a catalase environment24.

In vitro susceptibility to manuka honey has been demonstrated with Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, Serratia marcescens, Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus (including meticillin-resistant strains) and, interestingly, Candida albicans25,26.

A Cochrane review concluded: “Honey appears to heal partial thickness burns more quickly than conventional treatment (which included polyurethane film, paraffin gauze, soframycin-impregnated gauze, sterile linen and leaving the burns exposed) and infected postoperative wounds more quickly than antiseptics and gauze. Beyond these comparisons, any evidence for differences in the effects of honey and comparators is of low or very low quality and does not form a robust basis for decision making34.” Larger clinical studies are required in veterinary medicine to investigate the use of honey in wound healing.

Nanocrystalline silver dressings (NSDs) offer a slower release of silver ions into the wound compared with traditional silver dressings and creams (that is, silver sulphadiazine), which results in a longer acting, broad-spectrum bactericidal effect35. NSDs can be changed up to every three days, which is an improvement over the two-to-three times a day application required for silver sulfadiazine cream36.

Veterinary reports of NSDs are few, but include treatment of dogs and a cat (following burns, surgical wounds and necrotising fasciitis) using NSD with NPWT36,39,40. Large-scale veterinary studies are required to further corroborate the initially promising results for NSDs.

Additional novel techniques have been described in humans for treatment of open wounds, but little comparable veterinary data are available at this stage.

Explored modalities include: