30 Apr 2018

Victoria Robinson and Hilary Jackson discuss various ways of preventing and managing this condition, plus systemic and topical treatments available.

Atopic dermatitis is a genetically predisposed inflammatory and pruritic skin disease associated with the production of IgE antibodies, usually to environmental allergens (Halliwell, 2006).

It is a diagnosis of exclusion based on characteristic clinical signs and ruling out diseases with a similar clinical presentation, most notably ectoparasites, secondary infection and food sensitisation. Heritability contributes to almost 50% of the incredibly complex pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis, with environmental factors, skin barrier alterations, changes in the skin microbiome and parasitic exposure contributing the remaining 50% (Shaw et al, 2004; Marsella and DeBenetto, 2017).

Initial clinical signs of atopic dermatitis in dogs are frequently recognised in those aged between six months and five years. Pruritus is the primary clinical sign and typically involves the ears (canals and concave pinnae), periorbital skin, muzzle, axillae, antebrachial flexures, carpi and tarsi, ventral abdomen and perineum. Pruritus may be seasonal.

Cats, ever keen to prove they are not small dogs, present with clinical signs associated with one or more reaction patterns, including bilateral symmetrical alopecia, eosinophilic granuloma complex, head and neck pruritus, and miliary dermatitis. The role of IgE in feline hypersensitivity reactions is not as well documented as in dogs.

As such ”atopic dermatitis” in cats is known as hypersensitivity dermatitis, with flea, food and non-flea, non-food the most commonly used terms.

This article will focus on multimodal treatment and the reader is directed elsewhere to other articles on the pathogenesis and investigation of atopic dermatitis.

Atopic dermatitis is largely thought to be associated with a Th2 to Th1 imbalance. Langerhans cells capture allergens before migrating through the lymphatics to the lymph node.

Here, naive CD4+ T cells differentiate into Th2 helper cells, which produce IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-13 and IL-31 and stimulate B cells to produce IgE, as well as IgA and IgG. IgE binds to circulating mast cells, resulting in release of inflammatory mediators, and clinical signs of inflammation and pruritus on subsequent allergen exposure (Saridomichelakis and Olivry, 2016).

Optimal management requires time to assess the individual patient and discuss options with the client. Financial or time constraints may be considered. Management can also vary seasonally, with many pets requiring more treatment during the summer months when the environmental allergen burden is greater.

The skin barrier is an area under research in canine atopic dermatitis and no studies have been reported in cats. Topical spot-on agents have been designed to restore the normal lipid balance and organisation in the defective stratum corneum.

Preliminary studies suggest the use of these agents results in ultrastructural and functional improvement. The omega-6 essential fatty acid (EFA) linoleic acid is also an important component of epidermal lipids, and oral supplementation can increase the concentration of this EFA in the stratum corneum (Popa et al, 2011).

Recommendations are to use a combination of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. It should be noted the optimum ratio is not known. Most premium dog foods are well fortified with these fatty acids.

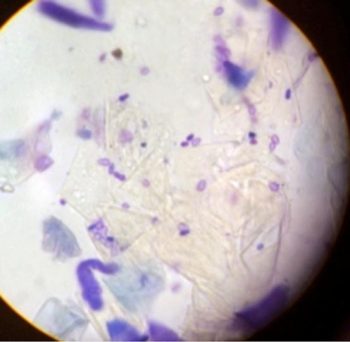

Secondary infections are common and can cause a flare in pruritus. This can be more extreme in patients with microbial hypersensitivity. Prompt recognition and identification of the offending organism (bacteria Malassezia) is imperative to determine appropriate treatment.

Cytology is particularly useful in this setting. Patients can present with similar clinical lesions at separate body locations associated with different infections (Figures 1 and 2). This patient responded excellently to topical management using twice-weekly shampoo and daily foam chlorhexidine-containing treatments.

Treatment choices are based on type of infection/overgrowth present, surface, superficial or deep infection, extent of lesions, and compliance of patient and owner. In many circumstances the use of topical treatment is effective and should be encouraged over systemic antimicrobials. Patients prone to microbial infections require long-term topical management, such as weekly antimicrobial bathing, foam or wipes to reduce the risk or rate of development of secondary infections. Topical treatment may not be possible in all patients or owners; therefore, a frank discussion is imperative to reduce the risk of ineffective treatment.

As ectoparasite infestations can mimic allergic dermatitis, this must be ruled out during the workup. Both infestation and hypersensitivity to ectoparasites can be a source of flare in patients with allergic dermatitis.

Excellent long-term ectoparasite control is required of not only the patient, but in-contact animals, too. This can be problematic with patients that attend day care, kennel facilities or go out with dog walkers, as it may be difficult to ascertain frequency of treatment with other in-contact pets. Demodicosis can develop in patients on long-term immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive treatment.

Assessment for ectoparasites should be considered in patients with previously well-controlled disease. A discussion into the mechanism of action, attributes and drawbacks of different products is beyond the scope of this article.

Cutaneous adverse food reaction can result in pruritic skin disease, and response to an elimination diet and provocation are warranted as part of initial workup. Patients with allergic dermatitis can also develop additional sensitisations during the course of their disease, which can include food.

Previously well-controlled patients with recurrent flares may require repeat elimination diets. Dogs or cats with confirmed food allergy may flare after ingestion of an allergenic food stuff, either through indiscretion or changes in the components of their diet.

Studies have shown presence of undeclared foodstuffs in several single protein commercial diets designed for the diagnosis and management of adverse food reactions. (Ricci et al, 2013; Horvath-Ungerboeck et al, 2017). Therefore, vets and owners should be aware of these potential pitfalls when choosing either elimination or maintenance diets in patients suspected to have food allergy (Olivry and Mueller, 2018). Owners should be guided on the suitable diets for their patients and changes to the recipe should be monitored.

Stress acts as flare factor in eczema in humans and it is possible stress management may be beneficial in veterinary patients with allergic dermatitis (Virga, 2004).

It should be borne in mind very few pruritic skin diseases have been found to be purely psychogenic in origin and a thorough workup is required to rule out all other possible pruritic skin diseases (Waisglass et al, 2006). Consultation with a behaviourist may prove beneficial in these cases where stress is suspected to be a component of disease.

Atopic dermatitis is a lifelong disease and treatment is aimed at keeping the animal comfortable and preventing secondary changes in the skin from occurring. Monotherapy is rarely effective.

Manifestation of atopic dermatitis varies, and treatment should be tailored to the patient’s needs and the owner’s expectations. A combination of systemic and topical treatments is generally required.

Allergen-specific immunotherapy is the only treatment shown to modulate the individual’s response to environmental allergens. Intradermal allergen testing or serology should be performed to help identify allergens that can be selected for bespoke immunotherapy. A careful history, knowledge of the environment the patient frequents as well as seasonal or non-seasonal occurrence of clinical signs should be ascertained to allow appropriate allergen selection.

It is very rarely possible or practical to employ allergen avoidance as part of management. Allergy testing should only be performed if treatment with immunotherapy can be undertaken and this may depend on patient, owner and financial factors.

Immunotherapy is usually considered a lifelong treatment and should be trialled for at least one year to assess the efficacy. It provides at least a 50% reduction in clinical signs in around 60% of patients (Nuttall et al, 1998; Lowenstein and Mueller, 2009). It is available in injectable and sublingual forms. It is well tolerated and severe adverse effects are rare. Other antipruritic agents can be safely used alongside allergen-specific immunotherapy. This is often necessary during the induction phase of the treatment to control pruritus.

Glucocorticoid (GC) treatment, systemic or topical, remains the mainstay of management of atopic dermatitis for many patients. Despite widespread use, the mode of action of glucocorticoids has not been fully elucidated. Treatment results in a reduction in production of inflammatory cells and mediators, and, thus, effectively controlling inflammation and pruritus (Saridomichelakis and Olivry, 2016).

GCs are fast acting and inexpensive. However, adverse effects include polyuria/polydipsia, polyphagia, behaviour change, muscle wastage, weight gain and skin atrophy. An increased risk of secondary microbial infection exists and the development of demodicosis. GCs can be considered for initial and long-term management of atopic dermatitis, as well as short-term treatment of flares. If long-term GC treatment is to be considered then tapering to determine the most effective dose should be performed (Olivry et al, 2015).

Ciclosporin is a systemic calcineurin inhibitor licensed for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in dogs and hypersensitivity dermatitis in cats. It acts to prevent gene transcription in T cells, which results in a reduction in cytokines, primarily IL-2, IL-4 and interferon-gamma, as well as reducing the number and activity of antigen presenting cells and mast cells (Forsythe and Paterson, 2014). This also results in an indirect reduction in proliferation of IgE producing B cells. The maximal effects of ciclosporin take several weeks of therapy.

For the very pruritic animal, additional initial treatment with oral GCs or oclacitinib for two weeks may be necessary. The combination, however, should not be continued long term. Ciclosporin should be considered for long-term management of allergic dermatitis and is not optimal for treating acute flares (Olivry et al, 2015). Although ciclosporin is generally considered safe, short-term side effects include vomiting and diarrhoea, which is often self limiting. Gingival hyperplasia and excessive hair growth are long-term side effects (Figure 3). Opportunistic infections can rarely occur.

Interactions with other drugs can occur and data sheets should be consulted if other medications are prescribed (Nuttall et al, 2014; Forsythe and Paterson, 2014). It is contraindicated in patients with neoplasia and serious infection.

Ciclosporin is available in several different licensed products in the UK, including capsule and liquid forms – which allows flexibility in product choice between patients. Daily doses can be tapered after two-to-three months of therapy in some individuals. The cost can be prohibitive for some clients.

Oclacitinib is a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor licensed for the control of pruritus associated with allergic dermatitis and atopic dermatitis in dogs above 12 months of age. It acts to block the JAK-signal transducers and activators of the transcription pathway, resulting in a decrease in cytokine production and receptor expression, chemokine production, lymphocyte proliferation and IgE production. This acts on cytokines IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-13 and IL-31, with the latter cytokine thought to be a key pruritogenic cytokine.

It is fast acting (as fast acting as a GC), effective and has a good safety profile. It is intermediary in cost between GCs and ciclosporin treatment (Saridomichelakis and Olivry, 2016). Common side effects include vomiting, diarrhoea, otitis, lethargy, weight gain and pyoderma (Cosgrove et al, 2015), and it is contraindicated in patients with neoplasia, generalised demodicosis and serious infection.

Routine monitoring of biochemistry, haematology and urinalysis is advised as haematological and biochemistry disturbances, and proteinuria have been reported (Cosgrove et al, 2015; Simpson et al, 2017). Furthermore, an increase occurred in reported histiocytomas in patients on long-term oclacitinib compared to treatment with ciclosporin (2.6% versus 0.6%; High et al, 2017).

Oclacitinib has been trialled in cats with hypersensitivity dermatitis. The results of these small-scale studies have shown limited efficacy for oclacitinib treatment in cats, except at considerably high doses in a small subset of patients. Furthermore, in one study, a mild increase occurred in the urea in 50% and creatinine in 25% of treated cats (Noli et al, 2017). As such, other licensed treatment modalities should be trialled before considering oclacitinib.

Oclacitinib can be used for the initial control of atopic dermatitis, acute flares and management of chronic cases in dogs. It can be used to control pruritus as required during elimination diets, as well as during the induction phase of immunotherapy.

Lokivetmab is a recent addition to the arsenal of treatments available for the management of canine atopic dermatitis. It is a caninised IL-31 monoclonal antibody that acts to bind IL-31, which is thought to be a major pruritogenic cytokine. It is licensed in Europe at a dose range of 1mg/kg to 3.3mg/kg to be given SC every four weeks. It has been reported to reduce pruritus by 60% and lesion score by around 45% (Michels et al, 2016).

It is not effective in all atopic dogs and the duration of action can vary between individuals. Side effects can include vomiting, diarrhoea and lethargy. Secondary microbial infections can be a complication of treatment as seen by the authors. If the first treatment is ineffective a second injection can be given a month later. If this second injection is ineffective then further treatment is not advised.

As this treatment is caninised treatment, it will not be effective in cats and should not be used. Lokivetmab can be used for short or long-term management of the atopic dog and as a relatively new treatment, long-term side effects are unknown. Lokivetmab generally sits between oclacitinib and ciclosporin in terms of cost.

Antihistamine treatment is very rarely effective as a sole treatment to control pruritus in patients already displaying clinical signs. However, proactive treatment with type I antihistamines, such as chloramphenamine, clemastine and hydroxyzine, may provide relief in patients with mild atopic dermatitis (Olivry et al, 2015). They will not be effective for treating acute flares, but may be useful as an adjunctive treatment for long-term management.

Topical agents are useful for treating focal areas of the skin, such as the paws or abdomen. They can be combined with systemic treatment and used either on a regular basis or intermittently as required. The main advantage is to minimise adverse side effects of treatment.

GCs are available as sole agents (hydrocortisone aceponate) or in combination with antibiotics (fucidic acid, dexamethasone). Proactive use of hydrocortisone aceponate applied to the skin on two consecutive days in patients with controlled atopic dermatitis was found to significantly reduce the length of time to flare (Lourenco et al, 2016).

Hydrocortisone aceponate is largely metabolised in the skin. No alteration occurred in ACTH stimulation, biochemistry or haematology when hydrocortisone aceponate was applied daily for 70 days (Nuttall et al, 2009). It should be noted local side effects, such as skin atrophy and calcinosis cutis (Figure 4), are possible with chronic use of topical GCs and patients should be monitored for such side effects. Topical application will not be possible in some patients with long hair coats.

The efficacy of hydrocortisone aceponate has been investigated in 10 cats with hypersensitivity dermatitis. A reduction in both pruritus and clinical lesion scores was seen when used either once daily or every other day during the two-month study (Schmidt et al, 2012). No adverse effects were noted with use over this period of time, but longer-term studies would be required. Furthermore, it may be possible to taper the frequency of application once patients are in remission.

Tacrolimus is a topical calcineurin inhibitor and has a similar mode of action to ciclosporin without the systemic effects. It is as effective as topical GCs; however, it is expensive and application to haired skin is difficult (Saridomichelakis and Olivry, 2016). As such, its use is likely to be limited to those patients that display unacceptable adverse effects to topical GCs, such as skin atrophy.

Allergen-specific immunotherapy and intermittent proactive topical GC are the only interventions for which sufficient evidence is available to prevent or delay flares (Olivry et al, 2015). A good strength of evidence exists for the use of systemic and topical GCs, ciclosporin and oclacitinib (Olivry et al, 2015).

A systematic review of the literature of the efficacy of lokivetmab has yet to occur given its recent addition to the market and paucity of independent studies. Finally, minimal sufficient evidence exists on the efficacy of antihistamines to manage flares (Saridomichalakis and Olivry, 2016).

Many well-controlled patients have periodic flares in their disease. This may be associated with the cyclical nature of atopic dermatitis and variable levels of allergen in the environment.

Secondary infections are a common consequence of flares, and consideration should also be given to acquired ectoparasite infestation or recent changes in diet (Panel 1). The history should focus on the owner’s current management plan, which might not always reflect your treatment plan. Often an answer to acute flare will become apparent during the history taking. A thorough examination of the skin, followed by cytology or further sampling techniques such as hair plucks or skin scrapes, is also advised.

For patients where flare is solely attributable to atopic dermatitis then short-term antipruritic agents, such as oclacitinib, prednisolone or topical GCs, can be prescribed (Panel 2). The authors usually find three to five days on these agents is sufficient to control a flare uncomplicated by secondary infections. Where acute flares are occurring frequently then the global disease management should be reassessed.

Around 20% of atopic patients present with erythematous, pruritic otitis as their only clinical sign. Management of these cases often differs from patients that present with additional clinical signs such as axillary or pedal pruritus. Systemic treatment, including ciclosporin and oclacitinib, is infrequently successful in the management of these cases.

Systemic or topical treatment with GCs is effective for the management of acute otitis externa. It aids pain, pruritus, inflammation and reduces cerumen production. Once infection is controlled, patients with erythematous otitis require long-term management specific to the otitis.

Use of topical or systemic GCs is often warranted. Long-term systemic treatment is often undesirable for a localised area. Furthermore, almost all available otic products licensed for use in the UK are polypharmacy products, including antibiotic and antifungal treatment. Use of these products for long-term management is not advisable given the concerns of antimicrobial resistance.

Inflammation associated with both erythematous otitis and acute otitis externa not only leads to increased cerumen production, but is also suspected to result in dysfunction of normal epithelial migration, which aids the ear’s self cleaning mechanism (Forsythe, 2016). Frequent topical ear cleaning will aid in removal of ceruminous build up and should be used in management of these cases. Ear cleaning should be performed every one to two weeks and care taken to not overly wet the ear canal, resulting in maceration of the lining and increased risk of otitis.

Erythematous otitis externa (Figure 5) can often be treated with local GC, either in a preventive manner or more often, depending on frequency of otitis and pruritus. Hydrocortisone aceponate has been found to be effective at controlling erythema when applied daily for 7 to 14 days then used proactively on 2 consecutive days per week (Bergvall et al, 2017). A triamcinolone product is marketed for the control of otitis externa and seborrhoea of the auricle when absence of infection is observed. This is a moderately potent GC and should be used with care.

Use of frequent ear cleaning, topical GCs and allergen-specific immunotherapy should aid with control of patients presenting with erythematous otitis. This will hopefully prevent progressive disease, such as stenosis, ceruminal gland hyperplasia and proliferative tissue, that can lead to the need for surgical intervention.

Allergic dermatitis in companion animals has a multifactorial aetiology and successful treatment requires identification and appropriate management of these contributing elements. It is unlikely the majority of patients will have controlled disease on a single treatment.

An in-depth discussion should be held with the pet owner so he or she is aware of the complexity of treatment and lifelong nature of the disease. Expectations for control of atopic dermatitis should be realistic, and the treatment plan should be manageable within time and financial constraints for the individual client.