2 Aug 2021

Sarah Caney BVSc, PhD, DSAM(Feline), MRCVS describes how the cause of this issue is diagnosed, as well as the management of patients affected by the condition.

Figure 1. Straining unproductively to pass urine is a medical emergency.

FLUTD is a term used to encompass a number of conditions that affect the bladder and urethra. FLUTD typically affects one per cent of cats and is characterised by clinical signs of cystitis. FLUTD is most common in young and middle-aged cats.

Several important medical causes of FLUTD exist, but idiopathic FLUTD – also known as feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC) – is the most common by far. Other causes include urolithiasis, urethral plugs, urinary tract infections and neoplasia.

The best outcome is achieved through confirming the precise diagnosis so that appropriate management strategies can be implemented. All cats with lower urinary tract disorders likely benefit from increasing their water intake, access to an “optimal” toileting facility and strategies to reduce stress in the home.

This independent article is sponsored and supported online by Vetark.

FLUTD is subdivided into obstructive and non‑obstructive disease. Cats with obstructive disease are unable to pass urine, often referred to as “blocked” cats (Figure 1).

Urethral obstruction is a veterinary emergency – cats with this condition may die within two to three days if not treated.

Cats with non-obstructive disease are able to pass urine and typically strain to pass small amounts of urine on a very frequent basis. The urine may appear abnormal (for example, bloody), the cat may show signs of pain when straining and periuria may be present due to the cat’s urgency to urinate. Causes are summarised in Table 1.

Diagnosis may require a full behavioural and clinical history, physical examination, blood and urinalysis, imaging (including contrast radiography) and possibly biopsy.

Typical clinical signs of FLUTD include dysuria, haematuria, pollakiuria and periuria. Acute episodes of FLUTD can be very distressing for cat and carer.

Feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC), the most common cause of FLUTD in cats, is currently considered to be an “anxiopathy” – a disorder related to chronic activation of the central threat response system (CTRS). It is thought this may develop as a result of genetic, familial and developmental factors.

For example, a traumatic experience to the queen when the kitten is in utero may sensitise the CTRS, leaving the newborn kitten susceptible to problems in the future.

A susceptible cat is one with a chronic perception of threat impacting on its nervous, endocrine and immune systems, with the end result of clinical signs related to a number of organ systems including the bladder and lower urinary tract (Westropp et al, 2019).

The clinical signs of FLUTD are interpreted to be the bladder’s response to stress in these cats. Stress, therefore, plays an important role in triggering and/or exacerbating signs of FIC.

Chronic and inescapable stresses are thought to be most important. Characteristics of a cat with FIC often include a cat that is asymptomatic when in a “stress-free” environment, but which suffers from relapses of clinical signs when stressed.

Obese cats and those with a less active lifestyle are often over-represented. The history in these cases may therefore reveal:

A behavioural history is important to look for evidence of tension with other cats in the household/neighbourhood and other causes of stress in the home that may be exacerbating clinical signs. If identified, these represent a key target for intervention.

Of key importance in the cat with FLUTD is establishing whether the urinary bladder is empty or full.

A cat with urethral obstruction and a full bladder needs emergency treatment.

Many cats with FLUTD will have an empty, possibly painful bladder on palpation and the remainder of the clinical examination may be unrewarding.

In older cats, signs of FLUTD may be associated with illnesses such as diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism and chronic kidney disease, so routine blood profiles are helpful in making an accurate diagnosis.

Urinalysis is a key component of investigations in all cats with FLUTD. Urine should be observed, and its colour, clarity and presence of gross contamination determined.

The urine specific gravity (USG) should be assessed using a refractometer. Urine may be defined as isosthenuric (USG = 1.007-1.015, same as glomerular filtrate), hyposthenuric (USG lower than 1.007) or hypersthenuric (USG higher than 1.015). A 5ml urine sample can be centrifuged, and the sediment stained and examined by light microscopy. Normal findings are summarised in Table 2.

Of prime importance for chronic/repeat cases are:

Monitoring litter boxes for occult haematuria: this can be helpful in detecting recurrence of problems at an earlier stage than otherwise might be possible (Figure 2).

Imaging via radiography and ultrasonography is recommended for cats suffering from repeated/persistent clinical signs.

FIC is a diagnosis of elimination – the role of imaging is to rule out other causes of the clinical signs, such as urolithiasis and neoplasia (Table 1). Positive contrast urethrography can be helpful in identifying urethral disease.

Advanced imaging, such as CT, is now being performed more frequently in cats with FLUTD, and excretory urography CT is now a recommended technique for ectopic ureter investigation.

In a small number of cases, a biopsy of the bladder or other associated lower urinary tract tissues may be indicated to confirm a diagnosis.

Management of FLUTD depends on the diagnosis made.

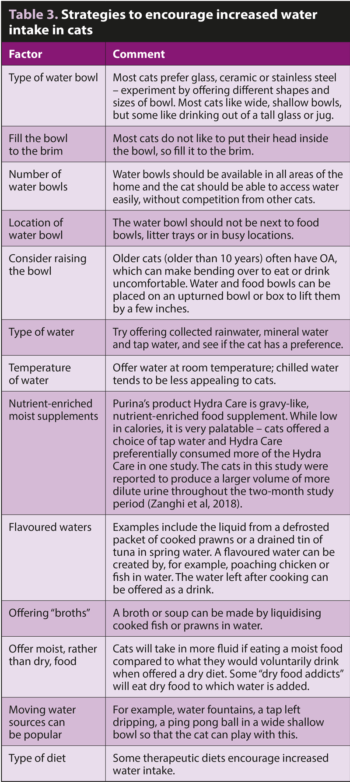

Almost all causes of FLUTD benefit from measures that increase water intake (Table 3). Success of these strategies can be measured through USG assessment (ideal is a USG lower than 1.035) and/or monitoring size of urine clumps if a clumping cat litter is used (Figure 3).

Providing an “optimal” toileting facility and adequate key resources for all social groups within the household is also vital.

Cats with FLUTD should have access to a litter box. This should be:

Dietary management is often a pivotal component of management in cats with FLUTD.

Specially designed urinary diets are effective in struvite urolith dissolution, reduction of crystalluria (relevant in cats susceptible to urethral plugs), and struvite and oxalate urolith prevention. Several maintenance urinary diets have now shown to be effective in struvite dissolution, meaning that a strict dissolution diet, which is typically very acidifying, is not needed.

For example, a Hill’s study indicated that while a dissolution diet (Hill’s s/d) took on average 13 days to result in stone dissolution, its maintenance urinary diet (Hill’s c/d) took a mean of 27 days (Lulich et al, 2013).

A more recent study involving a different maintenance urinary diet (Purina St/Ox) for cats with urolithiasis resulted in dissolution of struvite stones within two weeks (Torres‑Henderson et al, 2017).

Advantages of feeding a maintenance urinary diet include owner reassurance that the food is also safe for other cats in the household to eat. Unlike the situation in dogs, most struvite uroliths in cats are sterile and, therefore, antibiotic therapy is not usually required. Nonetheless, bacterial urinary culture is recommended in all patients with struvite stones, where possible, and is especially important in older cats where bacterial UTIs are more common.

General strategies useful in stone prevention include encouraging water intake with the aim of reducing relative supersaturation (RSS), a measure of the risk of crystallisation. Specially designed “urinary diets” are typically RSS tested with a formula that reduces the risk of stone and crystal formation.

In general, fluid intake is higher when a moist diet is fed, reducing the risk of stone formation, so this approach is preferred where possible. Additional dietary vitamin B6, glycosaminoglycans and long‑chain polyunsaturated fatty acids – commonly included in therapeutic urinary diets – are also thought to assist in reducing oxalate and struvite stone formation (Hall et al, 2017).

Successful long-term treatment of cats that have suffered from urethral plugs involves use of nutritional strategies aimed at reducing the number of crystals in the urine. Although it is normal for cats to produce crystals in their urine, especially if they are fed a standard dry diet, reduction of crystal numbers can help to reduce the formation of plugs. Specially formulated therapeutics diets, such as maintenance diets, designed for cats with FLUTD are recommended.

Dietary management is also of benefit in some cats with idiopathic cystitis. For example, feeding both dry or wet formulations of Hill’s Prescription Diet c/d Multicare Feline reduced the rate of recurrent episodes of FIC signs by 89 per cent in one study (Kruger et al, 2015).

Adding “stress‑alleviating” compounds – such as alpha‑casozepine and L-tryptophan – to therapeutic urinary diets has been reported to benefit some cats with FIC (Meyer and Bečvářová, 2016; Naarden and Corbee, 2020).

One study involving 31 cats with acute non‑obstructive FIC reported that feeding a therapeutic urinary stress diet (Hill’s c/d stress) was associated with a significantly lower recurrence rate compared to cats fed a variety of commercial diets. Again, in this study no significant difference existed between cats receiving wet versus dry formulations of food, although the numbers of cats involved was low (Naarden and Corbee, 2020).

Some dry formulations of therapeutic urinary diets contain increased salt (sodium chloride) levels which have been shown to encourage thirst and production of more dilute urine (Hawthorne and Markwell, 2004), therefore potentially benefiting many cats with FLUTD – especially those resistant to transitioning to a wet food.

FLUTD is commonly encountered in clinical practice. The best outcome is associated with an accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.

Providing an optimal litter box is important and where possible, monitoring urination can be useful in detecting recurrence at an earlier stage.

Dietary management is often helpful in management of cats with FLUTD, including cats with urolithiasis, urethral plugs and idiopathic cystitis.