6 Feb 2024

Luciana Santos de Assis discusses latest findings relating to this common canine problem.

Image © Eva / Adobe Stock

Canine separation-related problems (SRPs) are common and can affect dog welfare and human-dog relationships, where the animal can be relinquished or euthanised. These dogs are generally characterised by showing unwanted behaviours when left alone or separated from their owners at home.

SRPs is a syndrome with four presentations that reflect the strategies adopted by dogs when left alone, which can involve different emotions – especially frustration. Before establishing the dog has SRPs, the differential diagnosis for each sign needs to be performed by ensuring these behaviours only occur when the dog is alone. Afterwards, a detailed anamnesis, the use of the Lincoln Classification of Separation-related Problems Questionnaire, and recording the dog while it is alone are very important to help the team better understand and classify each case in one of the four forms.

Furthermore, the dog’s personality and relationship with its family should be assessed to evaluate the importance of indirect factors that may predispose the problem. Therefore, treatment should focus on both keeping the relationship between dogs and owners supportive and consistent, and the form of SRP presented to evaluate the potential importance of specific measures for managing the problem instead of using a generic treatment.

Keywords: separation anxiety, canine behaviour problems, emotions, attachment, frustration

Depending on the population studied, between 4% and 56% of dogs show unwanted behaviour when they are left alone or separated from their owners at home.

These problems can impact dogs’ welfare and dog-owner relationships, which might result in the animals’ relinquishment or euthanasia.

These dogs present signs of distress when separated from their owners, such as destructiveness, excessive vocalisation and house soiling. Additionally, they might present physiological signs; for example, excessive salivation, panting, trembling, repetitive behaviour (such as pacing), activity level changes and anorexia, which may also happen while the owner is preparing to leave (that is, pre-departure).

This behavioural problem has received many names, such as separation anxiety (SA), separation-related problems (SRPs), separation-related disorders and separation-related behaviours. The term SA is widely used, since dogs may look anxious in anticipation of being left. However, because not all dogs present anxiety, a general name is more appropriate.

Whatever the terminology used, it is important to appreciate that these refer to a syndrome with many causes that differ from case to case. This, together with the complex demands of a general treatment, means cases should not be approached as if a single treatment exists; therefore, delving deeper into the signs is important to aid understanding why the dog is displaying the behaviours of concern.

In the field of clinical animal behaviour, the importance of identifying specific emotions or motivations related to a problem behaviour has been increasingly recognised; for example, a dog can bark excessively when left alone at home because it is missing its owners, feeling frustrated for not being able to be outside, or reacting to something happening outside.

The author’s work (de Assis et al, 2020) has shown that SRP signs can be divided into seven groupings, which reflect a consistent part of the variation seen in different cases (Panel 1). These seem to come together to describe four behavioural profiles within SRPs, which involve different emotions/motivations.

The four forms of SRPs can be broadly described as follows.

This population is characterised by showing signs of exit frustration, attachment-related behaviours and redirected frustration at high levels.

These dogs may find being separated as aversive, and persistently try to follow their owners, but because they are unable to do so, they seem to struggle to find an alternative way of coping and, therefore, show redirected frustration.

These dogs seem to show low frustration tolerance.

All dogs show redirected frustration and reactive communication at high levels. Nearly all show attachment-related behaviours, and around 75% show signs of exit frustration (low level).

Although aggression towards their owners is a very rare phenomenon in SRPs, this is one of the groups that seems to feature it. These dogs seem to be reactive to external events, often trying to get at these stimuli, but because they are unable to do so, they remain highly aroused and struggle to find an alternative way of coping.

Accordingly, these dogs find being separated from their owners aversive, with the rare instances of aggression towards owners being indicative of a more general agonistic reactivity, which may explain why they are reacting to external events. Therefore, these dogs seem to have frustration and reactivity issues.

All dogs show signs of reactive communication (high levels) and nearly all show attachment-related behaviours (moderate levels). Signs of exit frustration are rare (less than 5% of dogs) and redirected frustration uncommon (about 20% – low level).

This is the other group that features aggression towards their owners. These dogs seem to be reactive to external events, but unlike the previous group, do not typically try to get at these stimuli. This may be, for example, because they are more generally anxious and avoidant.

This would be consistent with the absence of the owner being associated with a loss of social support, but the dogs perhaps finding some safety in the home, reducing their arousal. The rare instances of aggression towards owners may be indicative of a more extreme nervousness.

The boredom-related SRP population is characterised by a lack of consistency in signs across all dogs. Attachment-related behaviours are the most frequent signs (78.8%), although these are fewer than the other groups.

Redirected frustration and reactive communication are shown by most subjects, albeit the latter show friendly signs (wagging tails instead of barking).

Exit frustration is relatively rare (24% of dogs) and none show signs of aggression towards their owners. Therefore, these dogs may have learned that being alone is aversive due to a lack of stimulation, which leads them to destroy objects or attempt to escape.

Attachment is often discussed in relation to SRPs, but commonly misunderstood.

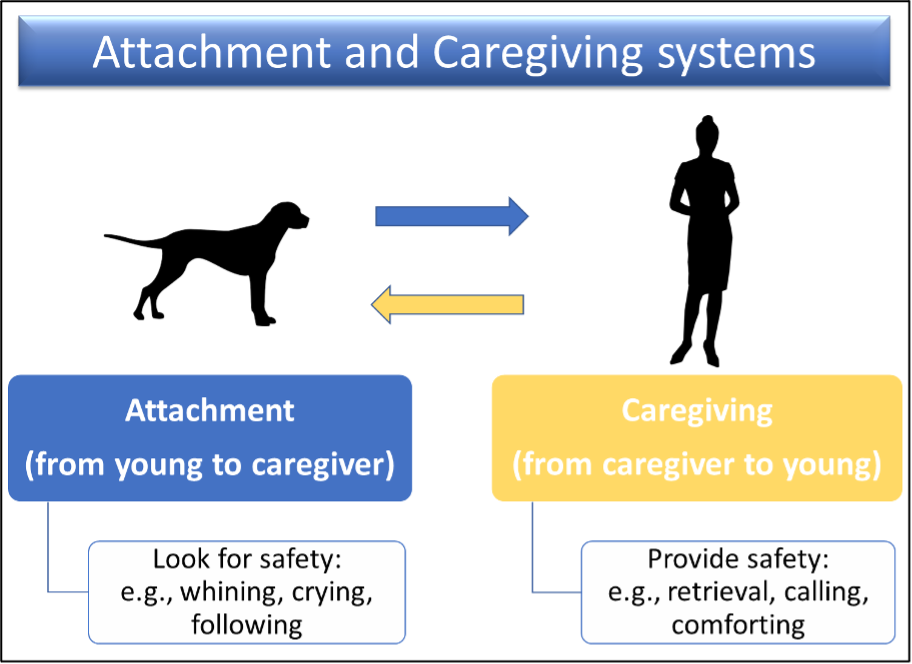

The attachment system has evolved to protect the young by maintaining proximity between the young and its caregiver. When the young animal needs to increase its proximity to its caregiver for safety and reassurance, it displays attachment behaviours such as vocalising, making eye contact and/or following.

Complementarily, the caregiving system aims to provide protection and stress reduction to the young through the maintenance of proximity between caregivers and them. The caring behaviours are reciprocal to the young’s attachment behaviours or are related to the caregiver’s perception of possible dangers; for example, retrieval, calling, seeking eye contact and/or comforting (Figure 1).

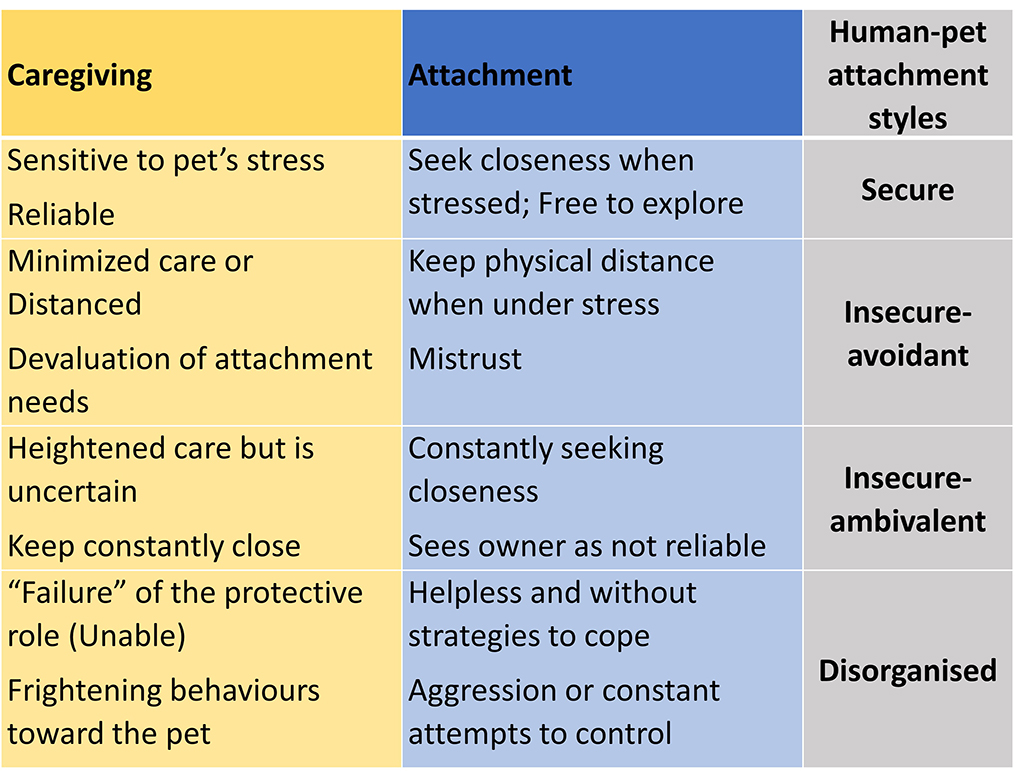

Dogs show signs of attachment towards their owners and, as with humans, can develop all four types of attachment: secure, insecure-avoidant, insecure-ambivalent and disorganised.

Accordingly, the attachment style of a dog depends on the caregiving style of its caregiver. Therefore, the secure style is when the caregiver is sensitive to, and addresses, the dog’s attachment needs who, in turn, trusts in the availability of its owner and seeks closeness and support in stressful situations.

The insecure-avoidant style is when the owner minimises care by keeping physical and/or emotional distance, and devalues the dog’s attachment needs. Consequently, dogs tend to not look for safety and reassurance from their owners under stress.

In the insecure-ambivalent style, owners exaggerate their care by keeping constantly close, but are uncertain. Therefore, dogs tend to constantly seek proximity to their owners because they are not sure safety will be provided.

The disorganised style is when owners do not feel able to look after their dogs – especially during stressful situations – and may give up on their protective role; therefore, dogs may not have strategies to cope, and may show aggression towards their owners (Figure 2).

SRPs may be related to how dogs perceive and react to their owners’ attitudes, which would vary according to owners’ caregiving style. Particularly, it might depend on dogs’ attachment differences and not some form of pathology in the dog relating to the intensity of their attachment (that is, hyper-attachment) as previously believed.

Hyper-attachment was thought to be similar to the attachment newborns show towards their caregivers, where they cannot survive without their mothers since they have no strategies to cope with being left alone (causing an intense negative emotion). Therefore, hyper-attached dogs would organise their lives around their owners so they could always be near them, by following and keeping close contact.

However, dogs with insecure-ambivalent attachment style would show similar behaviours towards their owners by constantly seeking closeness.

Although the term anxiety is often used in relation to these cases, frustration seems to play an important role in many of the four types described previously.

Frustrated animals can behave in different ways according to the context, including trying harder to achieve a desired goal, vocalising and showing aggressive behaviours. Many dogs with SRPs seem to become highly frustrated when left alone/separated from their owners. They can try to leave the house/room/crate and destroy it, destroy medium-sized objects as a redirected strategy to cope with their frustration, and they can bark or whine.

Dogs can become frustrated for different reasons in this situation, such as for not being able to follow their owners to reach what is happening outside, or to leave a place that they do not like. Understanding this is key to targeting appropriate treatment measures efficiently to manage a case.

Although it has been suggested that fear was an important cause of SRPs in dogs (for example, developing because of being left during a thunderstorm), it does not seem to be as common as thought, nor do SRPs originally triggered by this have a distinctive form.

Indeed, dogs showing noise phobias can be found in any of the four groups. This may be the case because SRPs seem to be more related to the lack of consistency and predictability of owners, which triggers frustration due to unmet expectations.

The differential diagnosis for SRPs needs to be performed by considering some of the following points:

After making sure the patient has problems only when left alone, a more detailed anamnesis is needed to identify the possible reasons. Additionally, the Lincoln classification of SRP questionnaire will help classify each dog into one of the four groups already discussed.

Recording when dogs are alone, as owners are preparing to leave and as owners return, is important to provide information about how the dog behaves, since some behaviours when left alone (for example, vocalisation) are more difficult for the owner to know of. Whether any other triggers are present, such as a noise from outside the house; analysing the dog’s body posture, which is more difficult for owners to identify; and how owners respond to their dogs are also possible.

Finally, based on assessment and which SRP type each dog fits, it is important to evaluate its behavioural tendencies, such as frustration tolerance and tendency to be anxious.

Additionally, understanding the relationship between patients and their owners (for example, the Lincoln Owner Caregiving Questionnaire) is important to understand the role of attachment in their SRPs.

Although the author’s aim is to focus on each group, general measures may still be recommended:

This group’s treatment should focus on increasing the frustration threshold by teaching dogs that waiting for the reward is worthy.

Desensitisation (and counter-conditioning) of being alone using a specific cue during the training sessions, and avoiding unpredictable departures, are important.

Teaching alternative behaviours for when dogs are left alone or giving them exercises to do in this period (for example, remote training) is very helpful.

Similarly, treatment for redirected reactive-related SRPs should focus on improving dogs’ frustration tolerance by specific exercises. Desensitise (with counter-conditioning) towards external stimuli and teach alternative behaviours according to the type of destruction performed (for example, using mouth or paws).

Although frustration is also involved in this group, the treatment could start focusing on teaching these dogs strategies for how to deal with stress, and increasing the dog’s independence and safety.

Desensitisation of external stimuli can also be helpful.

Focus on increasing exercises and play time so these dogs can spend their energy with their owners and not alone.

Adding activities for when the dog is left alone/separated, which should vary in type and difficulty level, is also important.