9 Apr 2024

Jack Reece discusses this condition that is being seen more frequently in the UK among imported dogs.

Image © Stock Footage, Inc. / Adobe Stock

In the past few years, an increase has occurred in dogs – especially young dogs – imported from Europe. These can be so-called “rescued” dogs coming from the eastern fringes of Europe or young dogs imported to satisfy the UK demand for puppies, which, again, may come from the eastern fringes, such as the Baltic states.

These increased numbers bring more risk of introducing exotic diseases into the UK.

Defra has indicated that the risk of the importation of rabies is very low, but has increased recently with the likely importation of animals due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Its assessment was carried out in 2011 and made the assumption that 100% compliance existed with relevant European rules.

While EU states in Europe have successfully controlled rabies by the use of oral vaccination baits for wildlife hosts (foxes and raccoon dogs), the Ukraine, Russia and Belarus still have large numbers of rabies cases, and these countries’ land borders with European countries, allowing for the possibility of spillover into countries from which dogs are imported into the UK. Other concerns are of the number of animals possibly smuggled into southern Europe from north Africa.

Defra was concerned enough about the possibility of rabies cases among imported animals that last year it held a webinar on rabies1. Rabies no doubt holds a particular horror for people, but especially in these islands2 where we have been free from indigenous animal cases for a century, had very few cases in quarantine and had only 29 imported human cases since 1902.

Rabies is an RNA Lyssavirus that causes an encephalitis – almost invariably fatal once symptomatic. Most (90%-plus) of the 50,000 human rabies deaths worldwide are caught from infected dogs, although the virus infects all mammals. The virus is carried in saliva.

Bites, licks or saliva contacts with mucous membranes and damaged skin cause deposition of the virus into the tissues. A period of viral replication follows in muscles. The virus is neurotropic and gains access to the host nerve tissue either directly or following replication in muscle. It then is transported by retrograde axoplasmic flow to the CNS and thence the brain.

Further multiplication follows, after which the virus moves outwards to the salivary glands, to eyes and other organs, and to peripheral sites. The incubation period of rabies is variable since it depends on the distance of the inoculating bite from the CNS and brain (the virus can travel at between 50mm/day to 100mm/day up axons).

Incubation period also depends on other factors, such as viral load, vaccination and health status. Typically, it is between 20 and 90 days. The infectious period, once the virus has reached the CNS, is 4 to 7 days and death follows within 7 days, but often, in the author’s experience, rather quicker. A dog may be infectious before it is symptomatic, which in endemic areas poses considerable difficulties since every potentially infected animal must be assumed to be infectious for rabies.

Rabies in dogs typically presents as either furious or dumb, though the distinction may be less clear than texts suggest. In the initial symptomatic stages, the changes can be subtle and non-specific. Pets may have a change in character; free-roaming dogs may become friendlier. Wildlife may lose its fear of man. Symptoms progress rapidly.

In the “furious” form, strange vocalisation, attacking objects and hyperaesthesia all occur, followed by ataxia and paralysis, coma and death. Some animals may self-mutilate. In the dumb form the animal may be subdued. A well-reported presentation is of a dog that behaves as if it has a bone stuck in its throat or mouth. Some rabid dogs are aerophobic and will react excessively if air is blown on their face; this mirrors similar symptoms in man.

Many rabid dogs show a thwarted keenness to eat, chewing and playing with food that ultimately drops from the mouth. Differential diagnoses in dogs include the neurological form of canine distemper, other encephalitides, neoplasia and trauma.

In cattle, the symptoms of rabies resemble those of BSE (S Watson, personal communication), and in the author’s experience, infected cattle may have a “tide mark” up the muzzle as the animal immerses its head in the water trough frustrated by an inability to swallow water. Equids can resemble a severe bowel torsion in behaviour and may attack and bite inanimate objects.

The strength of equids and the violence of the rabies symptoms can make control in these species challenging. Generally, rabies infection in large animals is considered to be a “dead end”. Certainly the author has seen a rabid horse bite a foal severely on the neck multiple times, yet the foal never developed the disease.

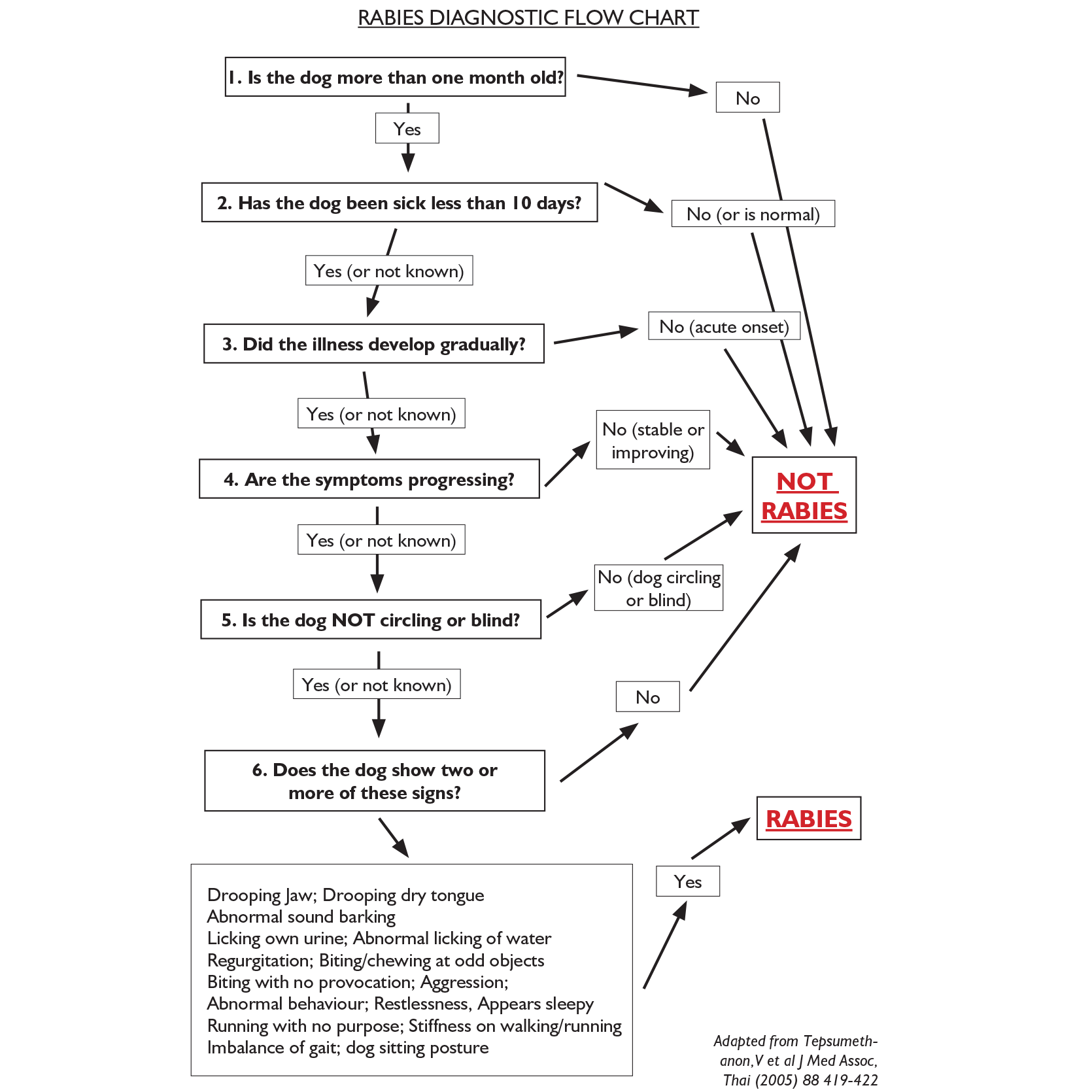

Laboratory diagnosis of rabies is possible only at postmortem. The clinician in practice is therefore presented with something of a diagnostic challenge, given the urgent need to identify potential cases of rabies. In charity practice in India, where rabies is endemic and free-roaming dogs are the largest class of patients, we use a diagnostic flow chart (pictured below) developed from research, to which the author was referred by leading rabies virologist Alex Wandeler.

Tepsumethanon et al3 determined the predictive value of clinical signs in rabid dogs and correlated these with the definitive “gold standard” postmortem diagnostic test of fluorescent antibody test on brain smears. This study showed that the use of the six identified clinical criteria was accurate, with 90.2% sensitivity, 96.2% specificity and 94.6% accuracy.

Laboratory diagnosis of rabies from brain smears using the fluorescent antibody test is a relatively simple procedure to perform, but a challenging test to read, and requires a fluorescent microscope, which is expensive and requires a dark room.

To overcome these difficulties in the developing world, where most rabies cases occur, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the US developed an immunohistochemical stain for brain smears. This involved multiple staining stages, but was easy to read. It does not seem to have caught on.

Recently, a snap test for use on suspect rabid brains has been developed, which identifies the presence of antigen. Sampling suspect brains can be done fairly easily in practice, but requires near complete decapitation of the suspect animal to gain access to the foramen magnum.

In the UK, such matters are, of course, academic. Rabies is a notifiable disease and, therefore, anyone with suspicions of a diagnosis of rabies must, by law, contact the APHA, which – along with Defra and multiple other agencies – will take over the management of the case, including diagnosis.

Although rabies in man is 100% fatal once symptoms have developed, it is entirely preventable through vaccination. Pre-exposure prophylaxis is recommended for veterinary professionals who may be exposed occupationally. This is a course of three injections on days 0, 7 and 21 to 28. Vaccination, together with wound toilet, is effective after exposure.

Rabies virus is fragile and thorough wound cleansing with soap will reduce the potential viral load (any soap will do for this purpose). If no soap is available then thorough irrigation with water will reduce the viral load in a bite. In certain classes of wound, if rabies immunoglobulins are available, these should be infiltrated in and around the wound, and rabies vaccination given.

Contrary to popular misconception, the post-exposure vaccination course is no longer multiple painful injections of Semple vaccine into the abdominal tissues around the umbilicus.

Modern cell-culture vaccines are more effective and very much safer, though up to five vaccine doses may be needed in the days following exposure. In the UK, the decisions on all human post-exposure treatments are vested with the UK Health Security Agency.

Colleagues – particularly those dealing with imported dogs or at ports – should consider rabies when examining dogs with strange behaviour or neurological symptoms.