13 May 2019

Deirdre Mullowney discusses this haematological condition in a feline patient, including diagnoses and treatment.

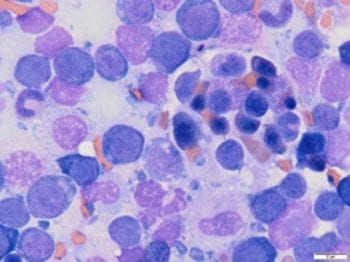

Rubriphagocytosis on cytology of a bone marrow core biopsy.

Cilla – a 10-year-old, female, neutered domestic shorthair – presented with a two-day history of anorexia and lethargy.

On physical examination she was quiet, but alert and responsive. Her heart rate was 204 beats per minute, with strong synchronous pulses. Her mucous membranes were pale. Abdominal palpation was comfortable and unremarkable. Peripheral lymph node palpation and oral examination were unremarkable. The cat was normothermic, with a rectal temperature of 38.3°C, and had a PCV of 9% and a total protein of 86g/L.

How can you diagnose precursor targeted immune mediated haemolytic anaemia (IMHA) in cats?

The main differentials to consider in an anaemic patient are haemorrhage, haemolysis and decreased production. In total, 10% to 20% of anaemic cats are diagnosed with IMHA1,2.

Blood smear examination is vital in the diagnostic work-up of anaemic patients. Signs of regeneration include anisocytosis, macrocytosis and polychromasia. Spherocytosis is a common finding in dogs with IMHA, but is difficult to identify in feline blood smears because their healthy red blood cells lack central pallor. Samples should also be assessed for evidence of macroscopic or microscopic autoagglutination, which is a simple in-house test that can help confirm a diagnosis of IMHA.

A positive direct agglutination (Coombs) test can be used to confirm the diagnosis of IMHA. Intracellular parasites, such as Mycoplasma haemofelis, may be seen on blood smear examination, although PCR testing is more sensitive.

Cilla’s blood smear showed little evidence of regeneration, with positive in saline agglutination test. She received a blood transfusion and her PCV increased to 16%. Treatment with immunosuppressive doses of steroids, ciclosporin and doxycycline, while awaiting M haemofelis PCR results, was started.

Primary IMHA is more common in dogs, whereas IMHA in cats is more often secondary. For this reason, it is important to look for causes of secondary IMHA, such as infectious diseases, neoplasia or drug reactions.

Cilla had a dental and was treated with meloxicam one month prior to presentation. PCR testing for Mycoplasma turicensis, Mycoplasma haemominutum and M haemofelis was negative. She was negative for FIV and had a weak positive result for FeLV. FeLV PCR testing on bone marrow samples was negative. Thoracic radiographs revealed no abnormalities. Abdominal ultrasound was performed, which showed a diffusely heterogeneous spleen. Urine obtained via cystocentesis had a negative culture.

Fine-needle aspirates of the spleen showed phagocytosis of polychromatophils and rubricytes, indicating precursor targeted destruction (PIMA).

After six days of immunosuppressive therapy, evidence of regeneration on blood smear evaluation was minimal. Bone marrow core biopsy and aspirates were obtained, and showed no evidence of neoplasia or myelodysplasia. Erythrophagocytosis was identified on the core biopsy.

Cilla remained bright throughout her stay in hospital and, once confident of a diagnosis of precursor targeted IMHA, Cilla’s owner was advised of the relatively good prognosis.

The reported mortality rate for PIMA is 27% and it can take at least six weeks before remission is observed3.

Cilla went home on ciclosporin and prednisolone 4mg/kg every 24 hours. Haematology was rechecked every two weeks to monitor for signs of relapse and the dose of prednisolone was gradually tapered by 25% every two to four weeks.