7 Nov 2023

Francesco Cian delves into the case of a seven-year-old Maine coon with a 24-hour history of severe dyspnoea in the latest “diagnostic dilemmas”.

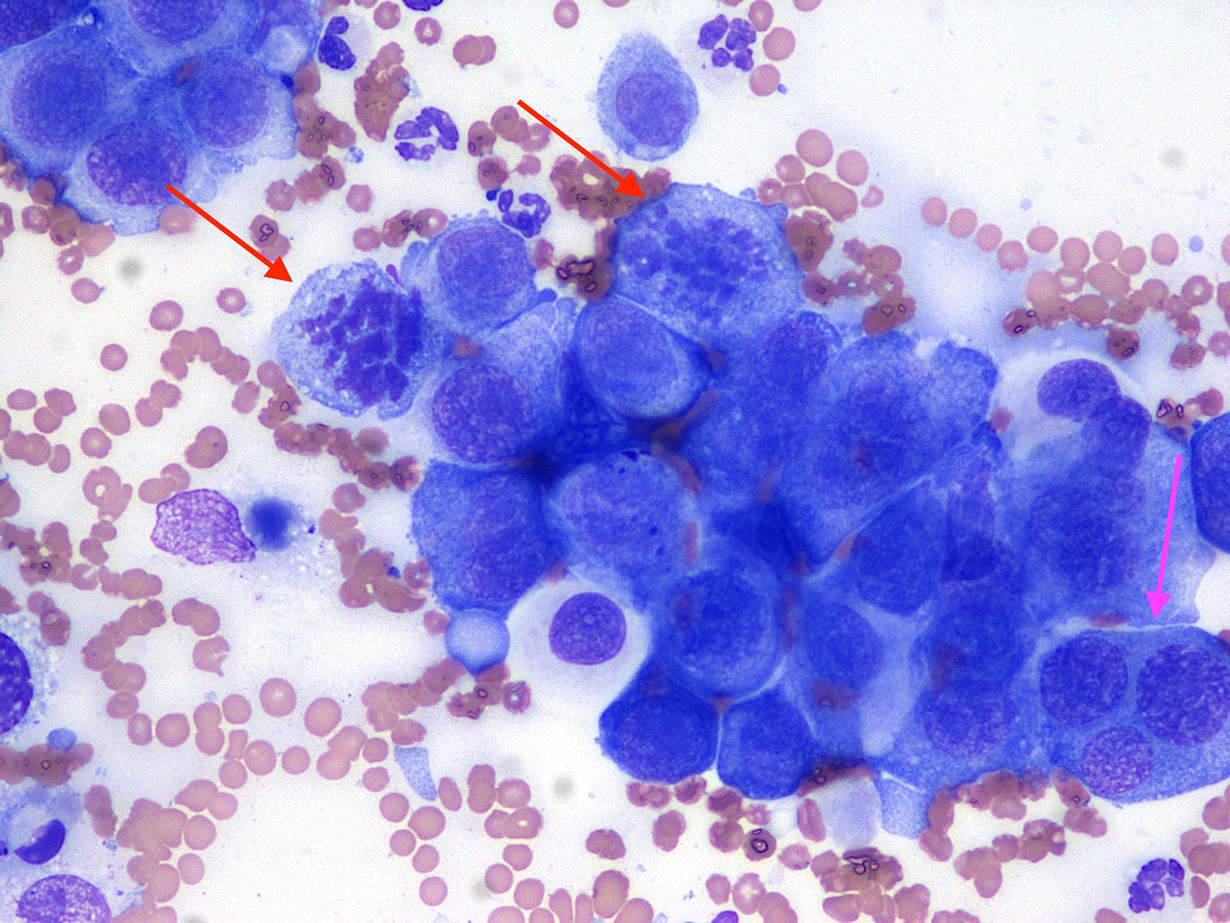

Figure 1. Pleural effusion (concentrated preparation; Wright-Giemsa, 50×).

A seven-year-old female Maine coon presented to the referring veterinarian with a 24-hour history of severe dyspnoea. Clinical examination and abdominal ultrasound demonstrated the presence of pleural effusion, which was drained for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, and submitted to an external laboratory for analysis (Figure 1).

Three months before, the cat was diagnosed with high-grade mammary adenocarcinoma with vascular infiltration and local lymph node metastasis. At that time, imaging studies did not show signs of distant metastases and the cat had a full-chain (radical) mastectomy.

The fluid appeared highly cellular with high protein content. A concentrated preparation obtained from the submitted fluid was examined. The background was clear with frequent red blood cells and a few segmented neutrophils, at least partially blood derived.

A population of round to polygonal cells was present, mostly arranged in variably sized clusters. These cells showed marked cytological features of atypia, including moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, prominent nucleoli, frequent mitotic figures (red arrows) and bi-trinucleation (pink arrow).

| Table 1. Cavitary effusion | |

|---|---|

| Thoracic fluid | Results |

| Macroscopic appearance | Slightly turbid and yellow fluid |

| Nucleated cells count | 24,310cc/uL |

| Red blood cells count | 28,000cc/uL |

| Total protein | 45g/L |

A diagnosis of carcinomatosis was determined.

Imaging studies were repeated after the fluid was drained. Thoracic radiographs revealed a diffuse, miliary nodular pattern throughout all lung fields consistent with pulmonary metastatic disease. The owners declined further investigations and treatment, and the cat was humanely euthanised.

Carcinomatosis is defined as evidence of seeding of neoplastic epithelial cells on any pleural/peritoneal surface and requires microscopic examination for confirmation.

Based on a retrospective study on more than 400 body cavity effusions in dogs and cats, carcinomas (including mammary tumours) and round cell tumours were the neoplasms most commonly encountered; sarcomas usually do not exfoliate.

The sensitivity and specificity of cytology for the detection of malignant tumours in body cavity effusions were 64% and 100%, respectively. This indicates that neoplasia can be missed by cytologic evaluation – usually because the tumour is not shedding cells – but neoplasia is rarely falsely diagnosed if the cytologist is experienced.

However, neoplastic epithelial cells can sometimes be difficult to distinguish from reactive or neoplastic mesothelial cells – in particular when they do not form clusters, which were seen here, but exfoliate as individual elements.

In those cases, further diagnostic investigations (for example, immunocytochemistry and histopathology) may be needed to confirm the origin of these cells.

Cytology is crucial for the interpretation of cavitary effusions, and diagnosis should not rely on total cell count and fluid protein only. Based on these data only, for example, this effusion could have been wrongly interpreted as an exudate – possibly part of an inflammatory process. On the contrary, it was mainly composed of atypical cells of epithelial origin; hence the diagnosis of carcinomatosis.