14 May 2024

Philip Witte discusses surgical management of stenosis and a case example of its use to treat obstipation.

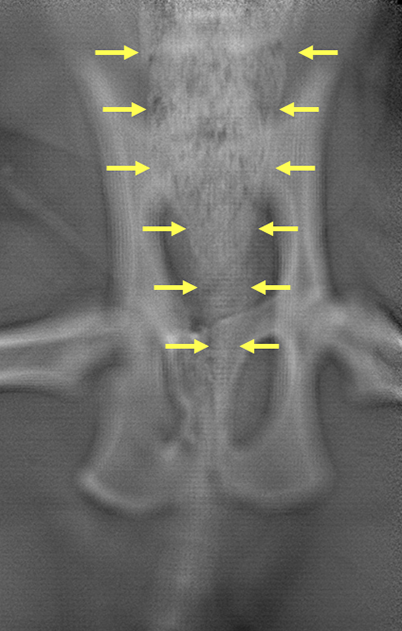

Figure 2. Lateral and ventrodorsal radiographic projections of the pelvis demonstrating malunion of the right ischium and pubis.

Pelvic fractures account for 20% of all fractures in cats (Bookbinder and Flanders, 1992). Malunion is the term applied to fractures that have healed without restoration of normal anatomy.

Malunion affecting the pubis or ischium in cats is rarely considered a concern, so orthopaedic surgeons typically do not address these fractures surgically. However, pelvic fractures affecting the “weight bearing axis” – the sacroiliac joint, ilium and acetabulum – should be addressed surgically. In the absence of fixation at these sites, as healing takes place, attempts made by the cat to load the hindlimbs will act to displace the caudal aspect of the loose portion of pelvis medially.

Following conservative management, pelvic fractures and sacroiliac luxations therefore often result in pelvic canal stenosis. In the worst cases, pelvic malunion and stenosis can result in dystocia, where the birth canal is affected in entire queens, or obstipation, in which chronic or repeated bouts of constipation are observed.

Management of obstipation secondary to pelvic fracture malunion may involve dietary changes including stool softeners and the occasional enema.

However, megacolon is one possible sequel to chronic obstipation. Megacolon is defined as a colonic diameter greater than 1.5 times the length of the seventh lumbar vertebra.

Although megacolon is usually idiopathic in cats, up to 25% of cases occur as a result of chronic untreated obstipation (White, 2002).

Surgical management of pelvic canal stenosis associated with pelvic fracture malunion has been reported in the literature. Typically in these reports, the healed injuries affect the sacroiliac joint or ilium and are often bilateral in nature, resulting in bilateral stenosis.

Techniques for surgical management include various ostectomies and osteotomies. Reported ostectomies include internal and external hemipelvectomy (Schrader, 1992; Liptak, 1998; DeGroot et al, 2016). Descriptive terminology of hemipelvectomy includes total hemipelvectomy, mid-to-cranial hemipelvectomy (removal of the ilium and acetabulum), mid-to-caudal hemipelvectomy (removal of the ischium and acetabulum) and caudal partial hemipelvectomy (removal of the ischium alone).

Terminology also divides hemipelvectomies into external and internal, in which the ipsilateral hindlimb is either amputated or preserved, respectively.

Hemipelvectomy is used for resecting neoplastic lesions, in which case limb amputation is sometimes necessary to achieve margin resection. However, for the purposes of treatment of pelvic canal stenosis, internal hemipelvectomy may be achieved alongside femoral head and neck ostectomy to preserve the limb despite removal of the acetabulum (DeGroot et al, 2016).

Descriptions of osteotomies for treating feline obstipation often involve modifications of the triple pelvic osteotomy (TPO) procedure, which is more familiar as a surgical option for young dogs with hip dysplasia. In the case of hip dysplasia treatment, the ilium, ischium and pubis are osteotomised.

The isolated acetabular segment of the pelvis is then rotated such that the acetabulum occupies a location more dorsal to the femoral head, therefore capturing it and reducing coxofemoral subluxation during the cycle of loading and unloading.

In the case of cats with pelvic stenosis, TPO is used to isolate the site at which the majority of the stenosis is likely to be present and to translate the implicated bone laterally. Reported fixation methods include plates and screws (Schrader, 1992; Ferguson, 1996) and lag screws following overlap of the cranial and caudal portions of ilium (Cinti et al, 2020).

One other technique described for widening the pelvic canal following stenosis is a symphyseal splitting approach. A ventral approach is made to the pubic symphysis, which is osteotomised along the midline and prised apart. Fixation of such a technique has been reported using ulnar autograft (McKee and Wong, 1994) and custom-made metal springs (Prassinos et al, 2007).

Outcomes for cats in these various studies following pelvic canal widening have overall been favourable. However, the data suggests that the prognosis for resolution of obstipation is superior in cases in which signs have been present for less than six months.

In one study reporting TPO in five cats with obstipation (Cinti et al, 2020), a measure of pelvic canal diameter was employed in pre-operative and postoperative radiographic images to quantify the success of the technique. This measure had been reported previously by Hamilton et al (2009) in a study documenting techniques for pelvic fracture fixation.

The measure is termed the sacral index. The sacral index is the ratio between the width of the sacrum at its cranial border and the distance between the medial acetabular walls made in ventrodorsal radiographic projections of the pelvis (it answers the question, “How wide is the pelvis at the level of the hips compared with at the level of the sacrum?”). Where the sacral index was below 45%, a high risk of obstipation existed (Hamilton et al, 2009).

However, this index is only a two-dimensional measurement, and obstipation will not necessarily follow in every case where the sacral index is below 45%. Consider, for example, a situation in which severe medial and ventral displacement of one hemipelvis is present. The sacral index would suggest significant narrowing of the pelvic canal, but it is possible that a wily rectum might find a way to snake through, without being compressed.

The pelvis is a three-dimensional structure. Two-dimensional imaging is no substitute for checking the pelvic canal diameter through digital per-rectum palpation. However, digital palpation only gives an estimate of the pelvic canal dimensions caudal to the point at which the finger can progress no further.

The extent of stenosis cranial to this point cannot be determined. In the interests of surgical planning, it may be useful for the surgeon to be aware of the cranial extent of stenosis.

Three-dimensional imaging, such as CT and MRI, has not been reported for evaluating disrupted pelvic canal dimensions in cats. Digital tomosynthesis (DT) is an imaging modality that has recently become available on the veterinary market (the Adaptix 3D veterinary imaging system), but is routinely used in human imaging for various clinical applications, including vascular imaging, dental imaging and mammography. As is the case for CT, DT produces images by combining data derived from standard digital radiographic imaging from multiple angles. However, in CT the source and detector usually rotate 360° about the subject, while in DT the source moves about horizontally, above the patient, achieving beam angles of up to 40°.

Processing of the DT data produces images not dissimilar to CT with a limited depth of field. In comparison with conventional CT, a significant reduction exists in the required number of projections, radiation exposure and cost (Dobbins and Godfrey, 2003).

The use of DT in human orthopaedics has been reported (Ha et al, 2015), and soft tissue DT information may be comparable to conventional CT, with detection of pulmonary metastatic disease for CT and DT having been shown to be comparable (Gomi et al, 2013). Use of DT is in its infancy in the field of veterinary medicine and its use for assessing the feline pelvis has not been reported.

In summary, three methods for determining the site and severity of pelvic canal stenosis exist: digital palpation per rectum, two-dimensional imaging (plain radiography) and three-dimensional imaging. For the surgeon to be fully prepared for surgery, three-dimensional imaging may be used.

The following case report documents use of DT to assess the pelvic canal and for planning of surgery (TPO) in a cat with obstipation as a sequel to complicated pelvic fracture malunion.

A four-year-old male, neutered British shorthair was examined for constipation. The cat had been acquired by the owners approximately 12 months previously and had initially demonstrated loose stools, which had been occasionally haemorrhagic – the passing of which frequently involved excessive straining.

Management changes including regular anthelmintic therapy and frequent small meals had resulted in a reduction in these signs, although the clients reported that the faeces remained soft and were never normally formed.

At almost five years of age, the client reported worsening of the signs, with the cat straining frequently to defecate, but only small volumes of faeces being passed. Abdominal palpation revealed large volumes of firm faeces in the descending colon and rectum. An enema was scheduled under general anaesthesia and when digital palpation revealed a stenotic pelvic canal, plain radiographs were acquired.

Radiography of the abdomen (Figure 1) revealed a full and severely distended colon. The seventh lumbar vertebra measured 17mm and the colon at its widest part measured 30mm, confirming megacolon. Views of the pelvis (Figure 2) revealed deformities consistent with malunion of the right ischium caudal to the acetabulum and of the pubis on the right side. The sacral index measured 71%, suggesting a low risk of constipation.

DT was used to identify the site of most significant pelvic canal diameter loss to determine the optimal approach for surgical widening of the pelvis. In addition to confirming pelvic fracture malunions (Figure 3), the DT image stacks demonstrated the exact site of severe narrowing of the colon and rectum at the level of the narrowing in the pelvis (Figure 4).

Somewhat surprisingly, the majority of pelvic canal stenosis, as identified by colon and rectum narrowing, did not appear to be associated with bone deformities.

Stenosis was largely associated with non-mineralised material within the pelvic canal. A generous mass of fibrocartilaginous callus within the pelvis was suspected. Additionally, surgical planning was aided by the appearance of a right obturator foramen, which was almost entirely occluded by the presence of the cranial aspect of the right ischium (Figure 5).

The obturator foramen is an important landmark in TPO, since two of the osteotomies (that of the pubis and the ischium) extend into this foramen. The narrowing of the pelvic canal and the level at which this was most severe was more clearly appreciable from the DT stack.

To address megacolon associated with pelvic stenosis refractory to non-surgical management, surgery was performed by triple pelvic osteotomy. Transverse osteotomies of the right pubis and ischium were performed through standard approaches. Performance of these osteotomies was complicated by both bones demonstrating remodelling, resulting in inadvertent release of a portion of the right ischium (including the ischiatic tuberosity) and a rather laterally located pubic osteotomy, close to, but not penetrating, the ventral acetabulum.

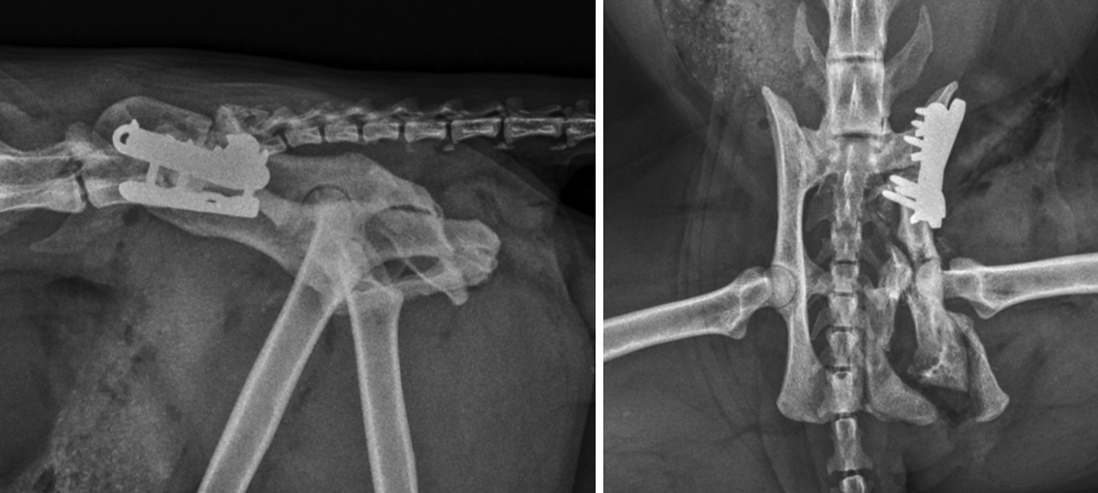

A transverse osteotomy of the right ilium was performed just caudal to the sacroiliac joint, and the right hemipelvis was translated abaxially. Fixation of the ilial osteotomy was with a laterally positioned 2.4mm locking tibial plateau-levelling osteotomy plate and screws – as previously described for fixation of ilial fractures by Guthrie and Kalff, 2018 – and a second parallel 2mm locking plate and screws. Postoperative plain radiographs were acquired after digital rectal palpation of the pelvic canal confirmed a significant increase in the pelvic canal diameter (Figure 6).

The patient was re-examined periodically up to 12 weeks following surgery. Lactulose was administered daily for the initial four weeks. Moderate right hindlimb lameness was present on examination after four weeks. Discontinuation of oral lactulose was commenced at this stage and progressed to completion over the following two weeks.

Eight weeks following surgery, right hindlimb lameness was mild with no resentment on examination. The clients reported that faeces were being passed on a daily basis and though the consistency was somewhat soft, no diarrhoea and no straining were present. Palpation of the abdomen failed to reveal distension of the colon or rectum. No evidence of a return of the clinical signs of obstipation existed 12 months following surgery.

Cats with pelvic malunion can develop obstipation. Identification of a narrow pelvic canal is typically performed by digital palpation. Plain two-dimensional radiography is often useful for assessing pelvic canal stenosis and surgical planning.

In the reported case, fractures were rather modest compared with previously reported cases and two-dimensional radiography was poor at identifying a cause for obstipation.

Three-dimensional imaging (DT; Adaptix 3D Vet Unit) was used in this report to identify the site of greatest pelvic canal stenosis and associated colon/rectal constriction. Following triple pelvic osteotomy involving fixation with two locking plates, the cat showed resolution of the signs of stenosis.