9 Apr 2021

Ariane Neuber DrMedVet, CertVD, DipECVD, MRCVS looks at causes, complications, clinical signs, diagnosis protocols, treatment and compliance in canine patients.

A dog with pinnal erythema as a hallmark of otitis externa.

Otitis is a very common clinical presentation. Analogue to pruritus, otitis is just a clinical sign and not a diagnosis.

Anyone who has suffered from ear disease themselves will know otitis is also a very painful condition. This is probably often underestimated, as many dogs do not show how much pain they are in. Due to the pain, otitis can severely impact dogs’ quality of life.

Many cases of otitis are recurrent and can become chronic. This is equally frustrating for the pet carer, the affected patient and the attending vet. A thorough approach is needed to deal with this presenting sign and it is better to avoid recurrence than constantly having to treat it.

Ear disease is multifactorial. What we actually see are the consequences of the real reason behind the issue: the primary disease. This can be one or several of the following:

The above condition leads to changes such as aural humidity, temperature, immunity and/or secretion of glands located in the ear canal, thereby altering the microbial flora and fauna, leading to a dysbiosis. This in turn leads to a further increase in glandular secretion and an altered immune response, which can be seen macroscopically by an increase of the ear wax and potentially a purulent discharge.

Due to their multifactorial nature, otitides are best approached in a very structured manner and examined with the primary, predisposing, secondary and perpetuating factors (PPSP) system described by JR August in the 1980s in mind. By evaluating all of the different facets of the issue, they can each be treated and followed systematically.

The primary factors have been named above.

Predisposing factors are conditions that already exist prior to the onset of disease. This can be anatomical features, such as pendulous pinnae, hairy ear canals or naturally narrow ear canals (for example, in Shar Peis) or lifestyle choices, such as swimming on a regular basis or plucking hairs out of the ear canal.

Microbial overgrowth by bacteria or yeast organisms constitutes the secondary factor. These organisms are usually part of the normal or transient flora in the ear canals, forming the ear microbiome. However, they usually exist in small quantities as part of a diverse mixed population, and in the diseased state one or few organisms multiply excessively and disturb the balance.

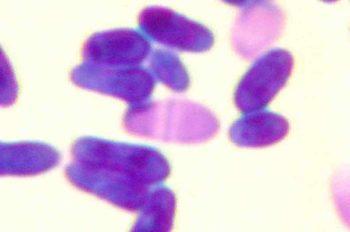

Organisms most currently encountered are Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (cocci) and Malassezia pachydermatis (yeast). Other organisms that can also be found relatively frequently include Streptococci, Pseudomonas, coliforms, Klebsiella, Proteus and Escherichia coli.

Perpetuating factors are defined as conditions that result from ear disease and make further episodes of otitis more likely to happen. This includes things like ear canal stenosis, hyperplasia of the ceruminous glands, scarring of the ear canals, otitis media (if caused by otitis externa) and in extreme cases calcification or even ossification of the ear structures.

To achieve lasting resolution of the clinical sign otitis, rather than performing a constant firefighting exercise, all the factors found when assessing the patient based on the PPSP system need to be rectified. A thorough work‑up needs to be performed and a long‑term management plan should be put in place.

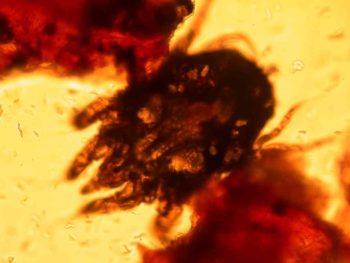

The workup starts with a thorough examination. This should ideally include a detailed history and a general, dermatological and otic examination, including otoscopy, cytology and potentially further tests. Clues in the history, or found during the general or dermatological examination, can sometimes help establish the primary factor. In some cases the otic examination reveals the primary factor – for example, a foreign body or ear mites.

Otoscopy can be quite painful if not done very gently – particularly if the ear is already inflamed and potentially stenosed, and the patient is potentially head shy due to previous negative experiences. In some cases, otoscopy is best delayed until the ear is more comfortable, perhaps after a short course of steroids.

For maximum patient comfort, the specula should be warmed to body temperature prior to using them in the ear canal. The right size for the patient must be chosen and the pinna should be stretched slightly upwards to ease examination of the bent ear canal. A good light source must be used to allow the deep structures of the ear to be seen – for example, the tympanic membrane.

Good patient restraint is important for this procedure, as sudden movements can result in pain and a negative experience for the patient.

On examination, the ear canal lining is normally smooth and a small amount of cerumen is normal. Wide breed variation exists as to the amount of hair growing down the ear canal, with breeds such as poodles often having very hairy ears. The normal tympanic membrane is also smooth and shiny, and should have a glistening, translucent appearance.

Usually, the manubrium of the stapes and an associated blood vessel can be seen; often a hair is coming from the level of the tympanic membrane.

Whereas otoscopy gives an overview of pathological changes caused by ear disease, cytology examines the nature of the infection and inflammation. This is one of the most important factors when following the progress of ear disease in canine patients.

As it is a relatively quick and cheap test to run if done in-house, it is a very useful tool in the assessment of cases of otitis. In most cases, sampling with a cotton bud is very well tolerated; however, head shy and aggressive dogs can usually still be sampled by gently inserting a gloved finger in each ear while massaging the ear canal.

The sample obtained is then dabbed on to a glass slide for staining and microscopic examination. Samples taken with a cotton bud are transferred to the slide by gently rolling the cotton bud over the glass slide surface a couple of times to achieve transfer of the material.

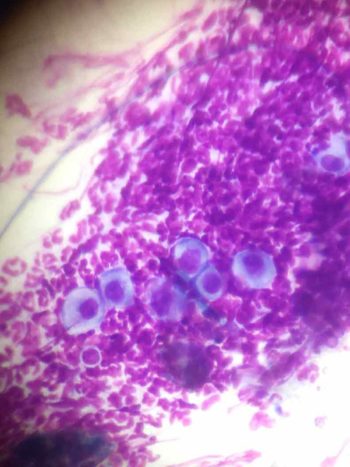

For cases where ear mites are suspected, a sample should be examined prior to staining; all other slides are stained with a modified Romanovsky-type stain system. For most applications, methylene blue staining alone is sufficient for the clinical application. Methylene blue stains bacteria, yeast organisms and DNA material, thereby making the major secondary factors and the inflammatory cells visible. If eosinophils or neoplasia are suspected, using all three stains is the better option.

As ear samples are very often heavily contaminated and a lot of organic material is present, which could be transferred into the staining jars, many people simply use a pipette to apply a drop of the stain solution on to the slide and rinse this off after a few seconds.

This type of stain cannot distinguish between Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria; however, the shape of bacteria is already very suggestive, as round bacteria (=cocci) are usually S pseudintermedius and rod-shaped bacteria are less predictable – so if this finding is made, a bacterial culture and sensitivity testing should be performed.

After fixing – if necessary – staining and drying, the slides are examined under the microscope. It is advisable to get an overview on low magnification first, and later go to successively higher magnifications under the microscope to examine the slide for organisms and inflammatory cells.

Find an area with plenty of purple staining on low magnification first and go up to 1,000× magnification under oil immersion. The author usually uses a drop of oil on the sample, followed by a cover slip prior to using the microscope. Another drop of immersion oil is needed when using the oil immersion lens. Of note are details such as which type of organisms and inflammatory cells are seen, and how many of each variety are present.

Many rods, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are less predictable in terms of the antibiotic sensitivity, and it is therefore advisable to identify if Pseudomonas is present. However, break points for sensitivity and resistance testing are derived from serum levels – and, therefore, if an organism is resistant in the laboratory test that does not automatically mean that it is a bad choice in a particular case.

Topical therapy can achieve far higher doses of antibiotic than can ever be achieved in the serum. In addition, certain compounds can be used in the ear to enhance the antibiotic action of the chosen medication. More important are factors such as amount, patency of the tympanic membrane and type of organisms.

Reducing the amount of debris, organisms and inflammatory cells in the ear canal is a very important aspect of managing ear disease. Using disinfectants rather than antibiotics is also an important part of antibiotic stewardship.

In cases with severe clinical signs and marked pain, and for certain types of organism as secondary factors, ear cleaning is best done under general anaesthetic in the first instance.

Performing an ear flush in an already very inflamed ear is exquisitely painful and very good analgesia should be provided. Using an endoscopic video-otoscope instead of a hand-held otoscope to examine the deeper portions of the ear canal and the tympanic membrane – as well as the middle ear if the tympanic membrane is defect – gives a far better view of the structures and enables the attending vet to perform a thorough flush.

The debris harbours microorganisms, allergens and inflammatory cell by-products, and almost shields the infective organisms from the antimicrobial therapy. Certain bacteria and yeasts have the potential to form a biofilm, affording further protection for the microorganisms. After a flush under general anaesthetic, most of the debris is absent, and this step is part treatment and part further examination.

In less severely affected cases, home cleaning may be sufficient. The frequency needs to be adapted to the type of infection and the amount of debris. Long-term preventive cleaning is often done once a week, but severe cases may require far more frequent cleaning – often up to twice a day.

Some cases require systemic therapy – particularly if extensive stenosis exists. A course of glucocorticoids helps reduce pain, “opens” up the ear canal and temporarily treats allergic skin disease, which is one of the most common primary factors.

Cases of ear disease caused by Otodectes benefit from treatment with selamectin, moxidectin or an isoxazoline.

If otitis media is present, systemic antibiotics or antifungals may be required.

However, the vast majority of ear cases can be treated with topical therapy alone.

Using topical agents in cases of otitis helps avoid use of systemic agents – particularly antibiotics – so is good for antibiotic stewardship. The ear is usually very accessible, and topical therapy can achieve high concentrations of medication, even overcoming resistance in some cases.

Main limiting factors are dogs with a lot of pain, that are aggressive or do not tolerate this way of medicating, and owners who are non-compliant. Non-compliance can be greatly reduced with thorough information about what the owner needs to do and why it needs to be done. Giving the pet carer a choice in what kind of treatment is appropriate and doable in that particular pet also helps increase compliance.

Building up a relationship of trust with the pet carer is very important. Many drops need to be given twice daily; however, products also exist that can be given once a day, once a week or one dose only. This obviously greatly increases compliance; however, long-acting ear gels are not suitable for every case.

If copious amounts of discharge are present this may reduce efficacy, despite cleaning prior to their use. Also, long-acting gels can find their way to the middle ear if the tympanic membrane is damaged, and can be difficult to remove from there, so can prove more harmful in such cases.

Certain types of infection do not usually respond well to the antibiotic in those gels. However, they are a good option for anxious pets and avoid the owner-pet bind from being disrupted by potentially painful treatments.

Most proprietary drops contain an antibiotic, a glucocorticoid and an antifungal component, and are polypharmacy. In many cases this is not needed.

Some cases benefit from long-term topical glucocorticoid administration alongside cleaning alone. The preparation should be chosen based on the organism involved, compliance and the clinical situation.

A multitude of cleaners are commercially available and they all have different properties. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss all ingredients in detail. However, each cleaner is very good at dealing with a specific clinical situation and must be chosen carefully with the patient in mind.

The nature of the discharge in particular and the infectious agent present are important factors for the choice of cleaner.

It is important to perform regular check-up consultations to monitor success and avoid just treating reactively. The primary disease must be identified and treated if prevention of ear disease – rather than a continuous cycle of otitis-treatment-remission-otitis and so on – is desired.

Cytology should always be a part of the re-examination routine, as the nature of the infection may well change and medication that was useful a week before may no longer be appropriate.

Many cases require more involved testing – for example, elimination diets, environmental allergy testing, or, in some cases, advanced imaging.

A long-term cleaning plan is also useful as part of the management plan. Choosing the right ear cleaner for the current situation is important in this context.