13 Feb 2017

Ariane Neuber looks at factors involved in canine ear disease, approach to investigation and therapy, and importance of early intervention.

Ear disease is commonly encountered in pet dogs and can be very frustrating to treat and extremely painful for the patient.

Each episode of otitis leaves the affected dog with tissue changes that make a future relapse more likely. The patient’s quality of life can be severely impaired. Owners can get very frustrated, as can the attending vet; ear disease is also a common reason clients change veterinary practice. It is, therefore, important to get it right from the beginning.

Just as pruritus is not a diagnosis, but merely a clinical sign, otitis is exactly that – a clinical sign and not a diagnosis. It is important to get to the bottom of all the factors involved and address as many of them as possible to achieve a long-term positive outcome, and gain the client’s trust and loyalty in the process.

Ongoing management will be needed for the majority of cases to achieve good quality of life and avoid surgery in more severe cases.

Otitis externa is inflammation of the ear canal. This is the most common form of otitis seen in dogs; however, if the inflammatory process is severe, or if traumatic rupture of the tympanic membrane occurs, the disease can extend in to the middle ear, leading to otitis media.

Primary otitis media is rare in dogs. The exception is primary secretory otitis media in cavalier King Charles spaniels. With this exception, most cases of otitis are an extension of severe otitis externa and there is quite an

Many factors are involved in the pathogenesis of otitis (Table 2). Essentially, these are divided into predisposing, primary and perpetuating factors, as well as secondary causes.

Predisposing factors are defined as things that contribute to the development of the disease, but, on their own, do not lead to clinical disease. These could be the anatomical structure of the ear (for example, very stenotic, horizontal ear canals, as seen in some Shar Pei breeds), excessive hair growth in the ear canal (for example, in poodles) or pendulous pinnae restricting air flow to the ear canal (such as in spaniels; Figure 2).

The disease process in otitis – particularly if treated suboptimally – leads to secondary changes, such as ceruminous gland hyperplasia, stenosis of the ear canal, scarring hyperplasia of the ear canal, and calcification or ossification of the cartilage, among others. These changes make the patient more prone to further episodes of otitis in the future and a downward spiral can develop. It is, therefore, important to intervene early, decisively and successfully to prevent this from happening.

Microorganisms such as cocci, rods and yeast are secondary factors in the disease process. The skin, including the lining of the ear canal, is usually inhabited by a large number of different microorganisms, forming the microbiome of these structures. In acute otitis, overgrowth usually occurs of one or more of the resident or transient organisms. Increased numbers of microorganisms push the patient over the comfort threshold and lead to clearly visible signs of otitis.

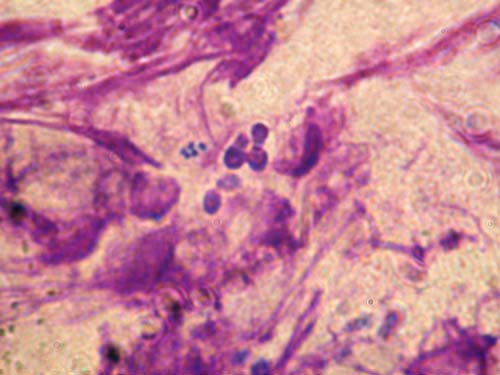

The most common microorganisms involved in cases of otitis are Malassezia species (Figure 4) and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. Streptococci, Pseudomonas (Figure 5), coliforms, Klebsiella, Proteus and Escherichia coli can also be found relatively frequently.

As staphylococci have a predictable pattern of antibiotic sensitivity and rods are more erratic in their antibiotic resistance pattern, it is important to identify the type of organisms involved in the infection. This will lead to a major difference in the treatment, prognosis and choice of further required tests. The most important test in the decision-making process for cases of otitis is, therefore, cytology.

With a bit of practice, cytology can be performed rapidly and without the need for expensive equipment in the practice – giving an answer to this important question straight away. When rods are seen on cytology, culture and sensitivity testing are indicated to make the most suitable antibiotic choice and give the client a more precise prognosis.

Otoscopy is another important part in the examination of patients with otitis. Due to the anatomy of the ear canal – with the bend separating the horizontal and vertical canal – this form of examination is needed to visualise the deeper structures of the ear. Due to the severity of the pain in many patients with otitis, this procedure may need to be delayed to a point when the affected animal is more comfortable.

Stenosis of the ear canal due to the inflammation in acute otitis can also be a prohibitive factor. A short course of glucocorticoids will help control the inflammation and “open up” the ear canal – making the patient more comfortable – and, hopefully, more readily allowing this kind of examination to take place. A good light source is important to visualise the deeper structures of the ear, including the tympanic membrane, on examination.

Medical and surgical otoscopes are available, as are video otoscopes (Figure 6) and digital otoscopes, which can be used to document changes in the ear canal. This can be an important tool for client education. Prior to performing otoscopy, it is important to warm up the ear cone to ensure best possible patient comfort during the procedure. Pulling the pinna up to stretch the ear canal during the examination facilitates reaching the vertical canal as comfortably as possible for the patient. Good restraint of the dog is also important to prevent causing damage to the lining of the ear canal during the procedure.

The ear canal should be smooth – possibly with a small amount of ear wax and some hair growth (with extensive breed variation) – and the tympanic membrane smooth, glistening and translucent in appearance. In dogs that have become head-shy due to painful ears, this type of examination may not be possible in aggressive animals and very painful patients with stenotic ear canals, so may have to be performed after a course of glucocorticoids or, in some cases, under sedation or general anaesthetic.

Cytology is probably the most important test in the investigation of ear disease. It is relatively easy and quick (with practice), cheap to perform in-house and gives an almost instant update of the state of each ear. With slight modifications, it can usually even be performed in the most fractious and aggressive animals.

In amenable patients, a cotton bud is gently introduced into the ear canal to obtain a sample of the otic discharge. This is then carefully rolled out on to a glass slide and prepared for microscopic examination. To save slides and time it is possible to use the same slide for samples from both ears by using the side next to the frosted end for the right ear and the opposite end for the left ear (or vice versa).

Romanowsky staining sets are most commonly used in practice. This type of stain cannot distinguish between Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms; however, the shape of the bacteria is very suggestive of this variable (with the exception of Corynebacterium, which is rod-shaped, yet a Gram-positive organism). Various methods have been described and, to some degree, reflect personal preference. Waxy samples can be heat fixed, but more purulent samples are air dried and fixed with the fixing solution before being immersed into the eosin red stain followed by methylene blue stain.

Many dermatologists will simply use a drop of methylene blue on the sample, rinse, dry and examine the slide microscopically. This will result in visibly less cell detail; however, for most ear samples, it is time saving and perfectly adequate. Once the sample has been stained and dried, a drop of immersion oil is applied, followed by a cover slip to reduce light beam scatter – resulting in a blurry picture – and the slide is examined microscopically.

The sample should first be examined under low magnification to get an overview and find a good site to examine more closely. An area with a good amount of purple-stained structures is then chosen for further examination. Higher magnification lenses are then used, perhaps up to a magnification that requires the addition of immersion oil on top of the cover slip. The most important details to note are the type and number of cells (for example, keratinocytes and neutrophils) and microorganisms (Figure 7). If rod-shaped bacteria are found, culture and sensitivity testing is indicated.

Ear cleaning is a very important aspect of otitis management. Debris harbours microorganisms. Certain antibiotics are inactivated by purulent material (for example, polymyxin B). Cleaning ears acts in a similar way to using a shampoo on the rest of the body in that it removes allergens from the ear, reduces the number of microorganisms mechanically and, depending on the chosen cleaner, actively works as an antiseptic.

Healthy ears are self-cleaning by a process called epithelial migration. This is the outward growth of keratinocytes from the tympanic membrane to the opening of the ear canal, which effectively removes the small amounts of debris present. This mechanism fails in otitis as it is overwhelmed by large amounts of otic discharge formed in a diseased ear. Without removing the debris it is not possible to examine the deeper portions of the ear canal.

The method is chosen in any given patient (home cleaning versus in-practice cleaning, conscious or under general anaesthetic) depends very much on the temperament of the patient, severity of the disease, ability of the owner to effectively clean the ears at home and nature of the infection. Small amounts of ear wax can be removed at home in an amenable dog with capable owners. Severely painful ears – for example, in cases of Pseudomonas otitis – require in-practice cleaning under general anaesthetic with very good analgesia, followed by top-up flushes at home. Cleaning is usually combined with ear drops containing antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agents. Follow-up appointments are vital to ensure successful therapy.

Topical therapy is able to achieve much higher concentrations of active ingredients than systemic therapy ever can. In the interest of antibiotic stewardship it is far preferable to expose only a small proportion of the patient’s microbiome to an antibiotic agent. This form of therapy should, therefore, be used whenever possible.

The vast majority of patients do not need systemic therapy, although it can be helpful in very select cases of otitis. For example, in cases of ear mite infestation, systemic preparations, such as selamectin or moxidectin spot-on, are useful. Some cases of otitis media can benefit from systemic antimicrobial therapy, but topical therapy can reach far higher concentration and should always be tried first in amenable cases of otitis externa. Patients with severe inflammation usually require systemic glucocorticoids to provide analgesia and reduce the swelling, as well as having an otoprotective effect.

Ototoxicity is possible whenever any substance reaches the middle and/or inner ear. This could be an ear cleaner, ear drops, inflammatory cells and their by-products, microorganisms and any of their secretions, or flushing solution to name but a few. However, in a clinical situation, ototoxicity is relatively uncommon. It is worth warning the owner of this risk – particularly if in-practice cleaning is carried out and if the integrity of the tympanic membrane is unknown. Clinicians need to be aware of substances that are more likely to cause problems and those that are deemed safe in the middle ear.

Fluoroquinolones, squalene, TrisEDTA, clotrimazole, miconazole and dexamethasone are deemed to be relatively safe in the middle ear, but no ear preparation is licensed for use in case the tympanic membrane is compromised and only anecdotal evidence exists to support this. Ticarcillin, polymyxin B, neomycin, tobramycin and amikacin are potentially ototoxic in dogs with a ruptured tympanic membrane.

Regular follow-ups are vital for successful long-term management of otitis cases. After a bout of acute otitis treated with a course of ear drops and regular cleaning, it is important to monitor progress with a clinical examination and follow-up cytology. In addition, the underlying primary disease needs to be investigated and managed.

Further tests, such as advanced imaging or allergy testing, may be indicated. A long-term strategy needs to be put in place to address the primary disease to prevent relapses. This often includes regular use of ear cleaners.

An integrated approach to deal with acute otitis and address the secondary factors – as well as investigate the primary disease and treat the perpetuating factors – is essential in all cases of otitis. Follow-up appointments should be performed to monitor progress and a long-term strategy needs to be put in place to achieve the best possible outcome.

Many cases of otitis benefit from referral – particularly cases of Pseudomonas otitis – as a deep flush under general anaesthetic with a video otoscope is extremely useful to help resolve the otitis, and a thorough investigation of the primary disease is needed to formulate a long-term plan and increase the quality of life in affected dogs.