13 Aug 2024

Cecilia Villaverde considers the part diet can play in preventing and managing these issues in cats and dogs.

Image © chendongshan / Adobe Stock

A number of conditions affect the renal and urinary systems in dogs and cats, and nutritional management plays a role in several of those1,2. The importance of this role varies depending on the specific disease and the location within the system. To decide on the best nutritional management, these patients must receive a nutritional assessment3.

The renal and urinary systems are quite different regarding their nutritional management. The dietetic pet foods (also called veterinary or therapeutic diets) formulated for the management of chronic kidney disease (CKD) are a distinct group to those formulated for the management of other diseases of the urinary tract. The latter mainly include diets formulated to prevent and/or dissolve uroliths.

Nutritional management is the cornerstone of the treatment of CKD, with long-term clinical studies showing that the use of diets formulated for this condition result in longer survival and lower risk of uraemic crises in both dogs4 and cats5,6 with azotemic CKD (diagnosed at International Renal Interest Society [IRIS] stage two or more advanced), which has also been noted in retrospective studies7,8. These diets have several characteristics2.

Phosphorus restriction is considered to be one of the most important dietary modifications.

The inability of the kidneys to excrete phosphorus can lead to hyperphosphataemia, renal secondary hyperparathyroidism and other endocrine derangements that can promote disease progression9.

Phosphorus-restricted diets can result in control of serum phosphorus and parathyroid hormone, as seen in cats10. Also in cats with CKD, feeding11 a phosphorus-restricted CKD diet resulted in decreased of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23, an important regulator of phosphorus metabolism) and decreased phosphate on those cats that were hyperphosphataemic. Measurement of FGF-23 in cats with early stage disease can help decide if the patient requires dietary phosphorus restriction.

Phosphorus restriction is, therefore, recommended for CKD patients; however, some risks might exist. In cats with this disease, provision of a phosphorus-restricted CKD diet can be associated with hypercalcaemia12,13. This can be normalised by attenuating the phosphorus restriction14.

Fortunately, the phosphorus content in CKD diets is variable among products, and some are marketed for early-stage disease and tend to be less aggressive in their restriction.

These diets can, therefore, be used to manage the development of hypercalcaemia associated with phosphorus restriction, while still getting the benefits of such diets. Other strategies to manage this hypercalcaemia, such as using CKD diets plus magnesium supplementation, are being investigated15.

“Nutritional management is the cornerstone of the treatment of chronic kidney disease.”

Protein moderation is considered important to reduce the formation of nitrogen waste products, while still meeting nitrogen and amino acid requirements. These diets, therefore, provide protein above the minimum requirements16, but are lower than average maintenance foods.

Discussion exists on what is the best protein provision in CKD patients – especially feline17 – due to worries about muscle mass loss. As such, dietary protein must be very high quality, with a good amino acid profile and digestibility to help meet these requirements, and maintain muscle mass.

A risk exists of inadequate protein intake in patients that are inappetent, so providing CKD diets that are palatable and rich in energy density18 can help maintain weight and muscle mass. Decreasing dietary protein can also help in renal proteinuria, which would be an indication to use a CKD diet in IRIS stage one.

One study in cats showed negative effects of low dietary sodium on glomerular filtration rate, kaliuresis and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis, without having any positive effect on arterial blood pressure19.

The sodium content in CKD diets tends to be less than average, but in some diets it is comparable to maintenance diets and, overall, is not restricted below requirements.

As for potassium, the content of this electrolyte varies from average to high. Feline CKD diets tend to be higher, as hypokalaemia is more common in this species20.

Hyperkalaemia can also be seen in some cases, and in this case, choosing a CKD diet lower in potassium than the current one is indicated. In dogs, potassium-reduced home-made diets can also help21.

Patients with CKD can be prone to water soluble vitamin deficiency associated with polyuria and inappetence.

Some research, mainly in dogs with experimental CKD, has shown that diets enriched in eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) can help slow down progression and degree of proteinuria22,23.

These fatty acids can be found in fatty fish and marine oils, and tend to be included in CKD diets in variable amounts. The recommended dosage in dogs with proteinuric CKD24 is 140mg EPA and DHA per kilogram of metabolic bodyweight (kg0.75), and supplementation can be considered if diet alone does not meet this value.

Supplements should be assessed for both potency and safety, as fish oil sources can have safety risks25.

Patients with CKD are prone to acidosis, given the important role of the kidney on acid-base balance.

Diets for CKD, therefore, tend to alkalinise, which makes them unique in the case of cats, where maintenance diets are mildly acidifying to prevent struvite urolithiasis. These diets tend to be higher in antioxidants and can also contain prebiotic fibre.

Last, but not least, is energy provision. Patients with CKD can be prone to weight loss, and together with inappetence and low body condition score, this has been linked to a shorter survival8,26-28.

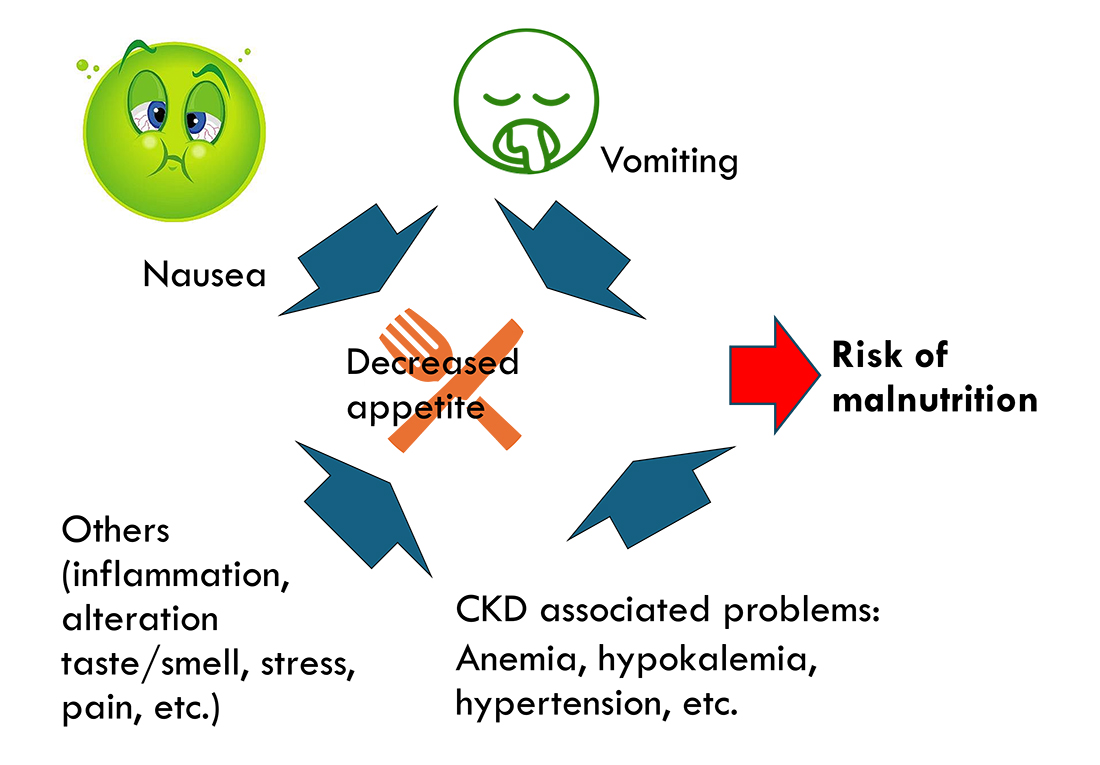

It is important to work up inappetent patients to identify the reason or reasons for the inappetence (Figure 1), as some are treatable. Appetite stimulants can also be considered29.

Additionally, calorie-dense diets can help provide the required energy in a smaller volume, which is beneficial in patients with poor appetite.

Palatability of the diet is also critical, and it is important to try different available options to identify the preferred ones by the patient. Rotating and mixing different CKD diets is also possible in many cases.

For later-stage disease, the use of feeding tubes might be required to meet energy needs with an adequate diet.

Offering other foods not formulated for CKD that might be more palatable for the patient can worsen azotaemia and accelerate progression, and this option should be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Dietary management is important in some types of urolithiasis1, together with other treatment modalities. The most common uroliths30 in dogs and cats are struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) and calcium oxalate, with urate-based uroliths in third place.

For a urolith to form, the urine must be supersaturated in the precursors, which must be in a specific chemical form to bond and crystallise. Other aspects – such as presence and concentration of inhibitors, urinary pH and urinary specific gravity (USG) – will also affect the process.

Methodologies such as the relative supersaturation (RSS) exist to assess those aspects globally. The RSS, which reflects the degree of urine supersaturation for a given crystal, has been used as a measure of stone risk in humans, dogs and cats31. While not practical for the clinical setting, companies can assess the RSS of their diets by feeding them to a group of dogs or cats, collecting their urine for a few days and analysing several parameters.

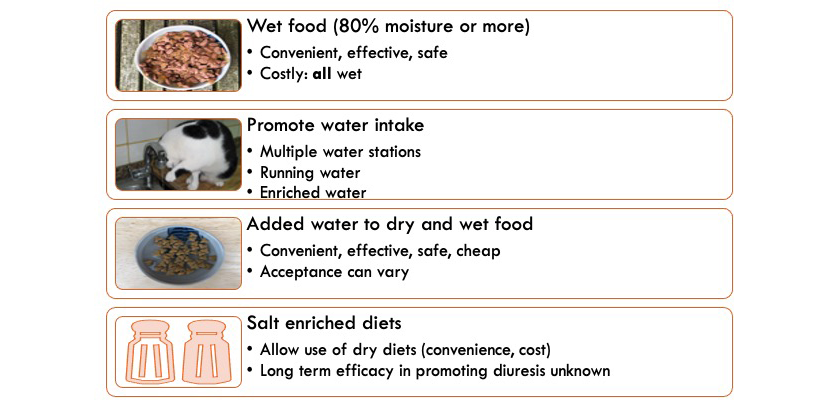

For all urolith types, promoting a dilute urine is potentially helpful, as it will reduce the concentration of crystallisation precursors and increase frequency of micturition, even though this is lacking in controlled studies. It is a common recommendation to aim for a USG of less than 1.03032. See Figure 2 for different methods to promote a dilute urine in dogs and cats.

Diet has been shown to dissolve struvite uroliths in cats and dogs33-35. Antibiotics will be needed in cases associated with urinary tract infections, which are the majority in dogs. Overall, diets for dissolution provide moderate amounts of the precursors (magnesium, phosphate, protein), promote low USG and acidify the urine – the latter being the most critical characteristic. As such, these diets must be fed exclusively, as the use of treats or other foods can alter the urinary pH and interfere with treatment.

Dietary dissolution is preferred to surgery, as it is less invasive32, but it can fail if the uroliths are not struvite or are of mixed composition.

Preventive diets have similar strategies, and dietetic pet foods exist that are formulated for both dissolution and prevention (and in several cases, also for calcium oxalate prevention). These are not needed in infection-induced cases, where prevention should focus on such infections.

Calcium oxalate uroliths cannot be dissolved with diet; its main role is in prevention. However, a lack of research exists backing up specific strategies to prevent calcium oxalate in cats and dogs.

Several epidemiological studies have been undertaken trying to identify dietary (and other) risk factors for calcium oxalate36-39.

One study in dogs36 found an association of higher risk with excessive calcium supplementation or excessive calcium restriction, excessive oxalic acid, high protein, high sodium, restricted phosphorus, restricted potassium and restricted moisture. Another one in cats39 noted that diets low in sodium or potassium, or formulated to maximise urine acidity, were associated with a higher risk of calcium oxalate, whereas diets with the highest moisture or protein contents, and with moderate magnesium, phosphorus or calcium contents, were associated with a lower risk. However, a lack of prospective data exists on how diet affects the formation of these uroliths.

While some studies exist supporting a positive effect of certain diets on calcium oxalate RSS and decreasing calciuria and oxaluria in healthy dogs40,41 and cats42-45, no good data exists on their effects on rates of recurrence. One study noted a urinary diet reduced calciuria in dog stone formers, but not to levels of healthy dogs46.

Another study47 in dog stone formers did not see a clear effect of a urinary diet on recurrence.

The effect of pH on prevention is controversial, and diets marketed for calcium oxalate prevention vary in their approach, with more classical recommendations focusing on urinary alkalinisation. However, diets marketed for the prevention of both calcium oxalate and struvite promote acidification, as pH is critical for struvite calculi. A common recommendation is to at least avoid “excessive” acidification32.

Diets formulated for calcium oxalate focus on promoting a dilute USG, providing moderate (but not deficient) calcium and vitamin D, using low oxalate ingredients and low precursors of oxalate, such as vitamin C.

High oxalate ingredients to avoid include potatoes, spinach and other vegetables. Some amino acids rich in collagen are metabolised into oxalate, and their intake can result in oxaluria, noted in cats48. Collagen-rich (chewy) treats should be avoided.

In cases of comorbidities, some brands have dietetic pet food formulated for struvite and calcium oxalate prevention and other conditions, such as obesity management, which is very interesting, as being overweight has been associated to urinary disease49,50.