18 Jan 2010

Anna Jennings details effective methodologies for the treatment of liquefactive stromal necrosis, and explains how it can be rewarding to treat.

A melting ulcer. Note the mushy appearance of this dog’s cornea, typical of liquefactive stromal necrosis. This dog had already received several days of treatment – hence the infection is under control and it appears comfortable.

Liquefactive stromal necrosis (melting ulcers) may present acutely, or as progression from a previously diagnosed corneal ulcer.

These ulcers are most frequently seen in dogs, but also occur sporadically in cats. Animals with brachycephalic conformation are over-represented, and these ulcers are particularly frequent in breeds such as pugs and shih-tzus.

Corneal trauma is the most frequently suspected initiating cause with regards to subsequent bacterial infection. Chemical injury, particularly alkali burns to the cornea, can also result in melting ulcer development.

I have occasionally encountered progression of an indolent ulcer to liquefactive stromal necrosis following grid keratotomy. Matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) are enzymes usually responsible for the removal of dead cells and debris from the ocular surface. However, in melting ulcers, the number of these protease and collagenase enzymes becomes excessive, and can result in rapid destruction of the corneal stroma.

These enzymes may be released from certain bacteria, leukocytes or keratocytes. The bacteria most frequently responsible for these enzymes, and thus associated with these ulcers, are Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus species and Streptococcus species. Fungal organisms may also release these enzymes, but are rarely isolated from the corneas of small animals in the UK. However, climate change may mean keratomycosis becomes a more significant problem in the future.

Other risk factors in the development of liquefactive stromal necrosis include topical and systemic corticosteroid use, pre-existing keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) and the presence of systemic disease (diabetes mellitus or hyperadrenocorticism).

These cases are often presented due to the affected eye’s appearance. The cornea is oedematous (to a varying extent), and of gelatinous appearance. The ocular surface may also have a yellow or grey discolouration, and there is frequently a mucopurulent discharge. The position of the corneal ulcer is variable, but most frequently central. The depth of the ulcer should be assessed, with deep ulcers often exhibiting a crater-like appearance. The presence of a descemetocele is a concerning finding, and the possibility of corneal perforation should be considered.

The affected eye generally has intense episcleral congestion. Marked deep and superficial corneal vascular invasion often occurs in association with these ulcers. However, there is a lag period of at least 48 hours before this process begins. The degree of ocular pain apparent is variable, and brachycephalic dogs are often surprisingly comfortable due to their reduced corneal sensitivity. However, in some animals, there may be considerable pain and distress, limiting examination of the eye.

A Schirmer tear test value should be obtained from both eyes, unless the affected eye is very fragile or painful.

The reading in the ulcerated eye may not be representative due to reflex tearing, inflammation and use of medication. However, a low reading in either eye should arouse suspicion of underlying KCS. Intraocular examination may be limited due to an opaque cornea. However, it is important to establish whether there is an accompanying anterior uveitis.

Pupil size, the appearance of the iris and the presence of hypopyon or aqueous flare should be noted. Left untreated, melting ulcers can progress to corneal rupture, iris prolapse and panophthalmitis.

The clinical history and appearance of the eye is generally pathognomonic. A swab should be taken from the eye once corneal melting is present or suspected. This should be submitted for culture and sensitivity.

However, there is inevitably a time delay before these results are available, and treatment should be instituted immediately. In-house cytology is a straightforward technique, and possible in all practices that have a microscope.

This provides an indication of the number and morphology of the bacteria involved. The presence of significant numbers of cocci is suggestive of Streptococcus or Staphylococcus infection. However, if rod-shaped organisms are found, this should arouse suspicion of the involvement of P aeruginosa.

Most cases of liquefactive stromal necrosis should be hospitalised, providing 24-hour on-site nursing care is available.

Alternatively, with a competent owner and prior discussion, it may be possible to manage the situation from home and check the animal on a daily basis. In appropriate cases, initial cautious debridement of the cornea, under local anaesthesia and with a cotton bud, can be used to remove loose tissue and discharge. This reduces acterial load and allows improved contact of topical medication with the ocular surface.

However, this technique should not be used in cases with very deep ulcers or marked ocular pain. If indicated, self-trauma can be prevented with the use of an Elizabethan collar. In animals with significant periocular hair, trimming this area makes management easier.

In choosing a topical antibiotic, the causative organism should be considered. Gentamicin is most affective against gram-negative organisms, and is primarily used in Pseudomonas infections.

Topical fluoroquinolones such as ofloxacin have a more broad-spectrum activity. However, resistance of Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species to these antibiotics is an emerging problem. Accompanying use of systemic antibiosis is sensible, and suitable choices are amoxycillin/clavulanic acid or a fluoroquinolone.

MMP inhibitors should also be instituted to slow stromal destruction. Acetylcysteine can be used topically on an hourly basis. I have no personal experience of using this, but it is frequently cited in the literature. Alternatively, a topical EDTA solution can be used. I make this up by combining a bottle of hypromellose (10ml) with the contents of two large animal EDTA tubes, and apply it to the affected eye every two hours.

Autologous serum can also be used topically on a frequent basis, and combines anticollagenase activity with epitheliotrophic properties. The latter should be stored in the fridge and discarded after a few days’ use because it is potentially an excellent culture medium for bacterial growth. Tetracycline antibiotics are also reported to have anticollagenase properties, and oral oxytetracycline or doxycycline can be used as an alternative choice of systemic antibiosis.

Recommended regimes vary, but I generally advocate two-hourly topical antibiotics, alternated with two-hourly topical anticollagenase for 24 to 48 hours, depending on clinical improvement.

Pain relief is an important consideration, and is often overlooked. Systemic NSAIDs offer analgesia and address anterior uveitis. However, some ophthalmologists feel these can negatively affect corneal healing.

Topical NSAIDs should definitely be avoided, as these potentially retard re-epithelisation. Topical corticosteroids are contraindicated, as they potentiate MMPs.

Systemic corticosteroids should also be avoided unless essential for treating another preexisting condition. Using opiate analgesia should be considered in cases with significant ocular pain.

Topical atropine (1%) may be utilised in cases of anterior uveitis to effect. However, this should be used with caution in cases with reduced tear production.

Ocular lubricants may also be useful, particularly when reduced tear production is present. In cases where an underlying KCS is suspected, tear production should be closely monitored, and longer-term treatment with cyclosporine to stimulate tear production may be necessary. However, I would not usually start this therapy while an ulcer is present.

Local anaesthetics should not be used therapeutically, as they are epitheliotoxic and, therefore, retard the healing process.

Key points for topical treatment include:

Melting ulcer cases that improve with medical treatment alone can return home once the ulcer is stabilised. Ongoing medication is assessed on a case-by-case basis. These eyes should be regularly re-examined until the cornea is fluoresceinnegative.

A proportion of cases do not respond to medical treatment, and indications for surgical intervention include:

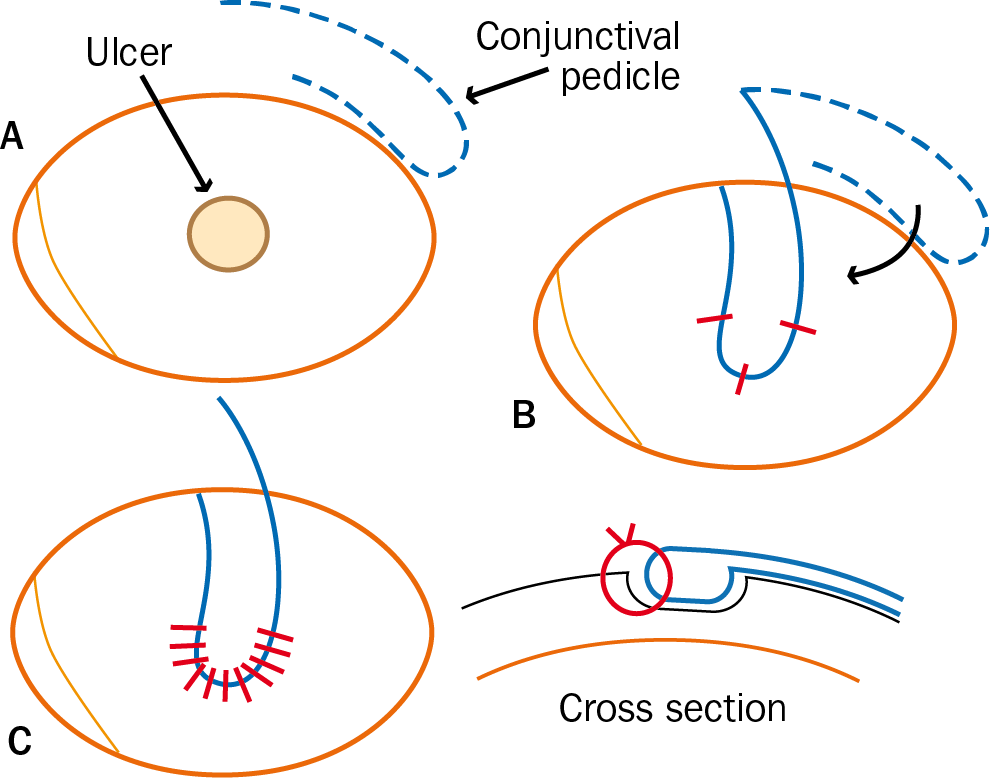

The most frequently used surgical procedure is a conjunctival pedicle flap. This provides structural support to the ulcerated area and a direct blood supply to accelerate healing.

Surgical intervention is generally carried out 24 to 48 hours after instituting intensive medical treatment. Prior to this, the infection present may be overwhelming and the cornea is often incapable of holding sutures, leading to a significantly increased chance of graft failure.

This is a fiddly procedure, and much easier with the assistance of an operating microscope. However, I do not think it is unreasonable to attempt this in general practice, when referral is not an option.

This surgery should be discussed with the owner in advance, as the postoperative appearance – particularly initially – can come as a shock. These grafts do permanently impair vision and can be associated with considerable corneal scarring, but they are an invaluable tool for treating deep ulcers.

This surgery has a reasonable prognosis, as the most common postoperative problem is graft failure if the sutures “cheesewire” through the cornea.

Pedicle grafts are usually sectioned three to eight weeks after surgery. This is often possible in conscious patients through the use of local anaesthesia, and leaves an “island” of conjunctival tissue, which becomes less prominent with time.

I feel the use of third eyelid flaps for treating melting ulcers is contraindicated. These impair contact of topical medications with the ocular surface and prevent visualisation of the cornea, meaning rapid deterioration can go unnoticed.

More sophisticated surgical techniques, such as corneoscleral lamellar transposition, are available and associated with significantly less scarring and visual impairment. However, this procedure is only appropriate in selected cases and requires considerable expertise.

Melting ulcers should be viewed as an ophthalmic emergency. Their prognosis is variable, and dependent on the time to presentation and the rapid institution of appropriate treatment. Unfortunately, in advanced cases, enucleation may be necessary, such as in the presence of panophthalmitis or a long-standing iris prolapse.

However, these cases can be extremely rewarding to treat, and once you have seen a melting ulcer, you will never forget it.

* Updated 15 June 2022.