9 Jan 2017

Sarah Caney examines ways to identify causes of this condition to assign the correct treatment and management options.

Figure 1. Living in a multi-cat household, especially one where there is tension between the feline lower urinary tract disease cat and other housemate/s, is a known risk factor for feline idiopathic cystitis.

Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) affects up to 10 per cent of pet cats worldwide and is most often characterised by episodes of cystitis. Affected cats typically pass small amounts of bloody urine, often showing pain and difficulty when doing so.

FLUTD can be caused by many conditions, including urolithiasis, bacterial urinary tract infection, bladder neoplasia and idiopathic cystitis. Successful treatment depends on identifying and treating the cause of the problem. However, the majority of affected cats suffer from idiopathic FLUTD, also known as feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC).

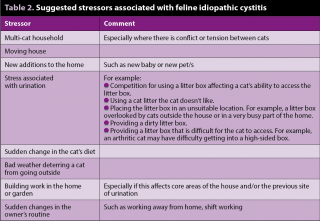

Management of FIC cases requires a multimodal approach with attention to identifying and addressing sources of stress to the cat, encouraging water intake, good litter tray hygiene and other strategies that will be discussed in this article.

Optimal treatment of feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) depends on identifying the cause of the problem.

Feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC) can be obstructive or non-obstructive. Male cats are most vulnerable to obstructive disease and need emergency treatment. Clinical signs of non-obstructive FIC are usually self-limiting, although most affected cats suffer from repeated episodes of clinical signs that can be very distressing to both cat and owner. In general, the frequency and severity of these episodes gradually decreases with time.

Successful management depends on a long-term commitment and team approach between the cat’s care provider and the veterinary professional. Studies have shown it is possible to greatly reduce the frequency and severity of episodes of FIC for the vast majority of affected cats through:

Synthetic pheromone preparations, such as a facial pheromone and a cat-appeasing pheromone. The facial pheromone acts as a confirmatory signal the environment is safe and, therefore, must be used in conjunction with other environmental managements, such as ensuring adequate litter boxes exist. The cat-appeasing pheromone is referred to as the “harmony marker” and has been proven to decrease the frequency and intensity of conflict and tension in multi-cat households. Both can be used simultaneously or individually, according to the situation.

A behavioural consultation may be of value in cases not responding to the measures previously described.

Uroliths in the bladder and/or urethra are an important cause of FLUTD. Uroliths can cause inflammation through irritating the lining of the bladder. Struvite and oxalate stones are most common in cats. Persian and ragdoll breeds are more vulnerable to oxalate stones and these are more common in cats with idiopathic hypercalcaemia and older cats.

Nutritional dissolution is well established as a treatment for struvite urolithiasis. A randomised, controlled, double-blinded clinical trial has advanced our knowledge by evaluating the efficacy of two commercially available dry foods for struvite stone dissolution (Lulich et al, 2013).

The test diets were a dissolution formula and a preventive/maintenance food for cats with FLUTD. The cats were monitored via weekly abdominal radiography. Both diets were 100% effective in dissolving struvite stones, although the rate of dissolution differed. The mean time for dissolution was 27 days for cats receiving the dissolution formula versus 13 days for cats receiving maintenance food.

The authors reported that calculation of percentage dissolution at 2 weeks was helpful, since all struvite stones had decreased in size by 35% to 100% at this time point, for both diets. Minimal or no stone reduction at two weeks would be consistent with a different form of urolith, such as calcium oxalate. Although dissolution is slower with the maintenance food, it has the advantage of being a suitable long-term food that can be fed to all healthy cats in the household.

Compliance to the foods was high, with all cats reportedly accepting a sudden change in their diet.

Oxalate stones cannot be treated medically; therefore, oxalate stones need to be removed surgically. Urethral oxalate stones can be flushed back to the bladder for surgical removal from here or they can be expelled from the body using voiding hydropulsion.

Cats that have suffered from urinary stones are vulnerable to repeat episodes of this problem. Fortunately, several specially formulated diets are available that help reduce the risk of recurrence of stones. However, the type of diet will depend on the type of stone the cat suffered from, and other medical and lifestyle requirements. Where possible, the cat should be fed a moist diet or a diet designed to promote urine dilution and encouraged to drink as much as possible (Figure 2; Table 3).

Urethral plugs account for about 20% of FLUTD cases in cats less than 10 years of age and are a potential cause of life-threatening urethral obstruction. The plugs are made up of a protein matrix with some crystals (usually struvite). The matrix is formed from protein that has leaked through the bladder wall as a result of inflammation of the bladder lining.

Urethral plugs are often associated with FIC and most clinicians believe this is a subset of FIC. Rarely, urethral plugs can occur as a result of bladder stones, tumours or infections. The protein matrix can also cause a urethral obstruction even when no crystals are present. However, when crystals are present, these can become trapped in the matrix and make it more likely to cause an obstruction.

Urethral obstruction can be caused by the plug itself, but also can be caused by urethral spasm associated with the pain caused by the presence of FIC and/or a plug.

If a bacterial urinary tract infection is diagnosed then a course of antibiotics is indicated. The type of antibiotic and length of course depends on certain factors, including the type of infection, regardless of complicating factors such as urolithiasis, which also needs to be treated, and the results of the bacterial culture and sensitivity test.

Where concurrent systemic disease, such as chronic kidney disease, is also present, a course of antibiotics lasting several weeks may be needed to eliminate the infection.

Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC), adenocarcinoma, leiomyoma, and other tumours, have been reported in cat bladders. However, TCC are seen most frequently – either as isolated tumours, or arising secondary to chronic inflammation.

Where possible, the recommended treatment for bladder tumours is surgical removal. Unfortunately, the disease is often very advanced by the time many of these cancers are diagnosed and surgical removal may not be possible due to metastasis or infiltration of the trigone and/or ureters.

In cats where surgery cannot be done and in those where it has not been possible to completely remove the cancer, palliative treatment may be helpful. Some success has been reported with palliative meloxicam (Bommer et al, 2012).

FLUTD is an important cause of illness in cats and can be a distressing condition for both cat and carer. The best success rates are achieved by making an accurate diagnosis so the most appropriate treatment can be prescribed.

FIC is the most common cause of FLUTD and is best treated using a multimodal approach taking consideration of all of the factors discussed in this article.