13 Sept 2022

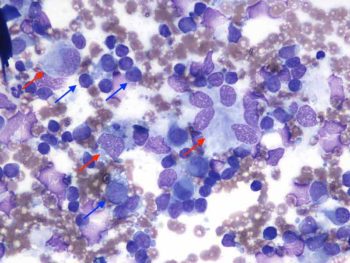

Figure 2. Fine needle aspirates from the left prescapular lymph node in an adult English springer spaniel dog (Wright-Giemsa, 50×).

A five-year-old male English springer spaniel presented for recent onset of lethargy. On clinical examination, the dog was pyrexic and showed a mild enlargement of submandibular and prescapular lymph nodes, and mild ventral cervical swelling. Fine needle aspirates from the lymph nodes were collected and submitted to an external laboratory for examination (Figures 1 and 2).

Both lymph node aspirates were highly cellular and well preserved. The background appeared clear to lightly basophilic with variable numbers of red blood cells.

A main population of lymphoid cells was observed – mostly small lymphocytes (blue arrows) with lower percentages of intermediate to large lymphoid cells, admixed with variable numbers of histiocytic-macrophagic elements (red arrows).

These cells were either individualised or arranged in small groups. They ranged from round/mononuclear to slightly elongated and had moderate amounts of lightly basophilic cytoplasm, slightly vacuolated with irregular, often wispy borders. Nuclei were round to oval, with coarse granular chromatin and visible nucleoli.

A diagnosis of histiocytic/macrophagic lymphadenitis was made.

Complete blood count showed mild leukocytosis with neutrophilia, biochemistry was overall unremarkable. Bacterial culture from lymph node was negative and so was PCR for Borrelia burgdorferi. Thorax x-rays and abdominal ultrasound were both unremarkable. The dog received glucocorticoids and showed remission of symptoms and lymphadenomegaly within a week.

The term lymphadenitis refers to lymph node inflammation and is characterised by leukocyte infiltration; this is often, but not always, accompanied by reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (as seen here). When histiocytes/macrophages are in increased numbers, lymphadenitis is referred as macrophagic or histiocytic. This type of inflammatory response is often triggered by stimuli such as infectious agents (for example, selected bacteria, fungi and protozoa) or foreign material.

However, cases of sterile lymphadenitis with prevalence of neutrophils and/or macrophages have been described in young and adult dogs – often associated with cutaneous lesions sharing similar morphological features.

Idiopathic pyogranulomatous lymphadenitis has been recently described in a retrospective and multi-institutional study involving 64 springer spaniel dogs, but has been recognised for years in several breeds.

This disease presents as enlargement of more than one peripheral and/or internal lymph nodes, which are characterised by neutrophilic and/or macrophagic inflammation.

Diagnosis is made by exclusion of other infectious, inflammatory or neoplastic causes.

The aetiology is poorly understood and screening for infectious causes is usually unrewarding.

An immune-mediated aetiology has been postulated because most dogs have a good clinical response to glucocorticoids or other immunosuppressive treatment. This condition may selectively involve lymph nodes, or it may be a more systemic or multi-organ inflammatory process, including onset of inflammatory skin lesions.

In dogs, idiopathic pyogranulomatous lymphadenitis is a diagnosis of exclusion and, therefore, other causes of pyogranulomatous lymphadenitis must be ruled out first.

In particular, infectious aetiologies must be excluded before immunosuppressive treatment is started.