18 May 2020

Diego Rodrigo Mocholi DVM, MSc, PhD, MRCVS discusses the nerve blocks that can be administered to companion animal patients in the thoracic and pelvic regions, as well as techniques and considerations.

Locoregional anaesthesia techniques have evolved in veterinary medicine in the past decades.

The benefit of their use lies in focusing on the specific target nerve responsible for the pain sensation, and the decrease of systemic drug administration. Therefore, not only are they useful techniques for perioperative analgesia, they are also useful as methods to control postoperative and chronic pain.

Locoregional techniques have been shown to produce a desirable and positive effect on economics. A recent study demonstrated the decrease in cost for perioperative analgesia in dogs heavier than 15kg using a femoral and sciatic nerve blockade – compared to fentanyl systemic administration – when undergoing tibial plateau‑levelling osteotomy (Palomba et al, 2020).

This article will focus on locoregional anaesthesia techniques in line with reducing costs during daily veterinary practice and with no investment in specific equipment. Nevertheless, the author would always recommend performing ultrasound and nerve stimulator‑guided nerve blockade techniques to reduce the risk of complications, which are well described in the recommended literature.

The ventral roots of the sixth, seventh and eighth cervical (C6, C7 and C8, respectively) – and the first thoracic (T1) – nerves leave the intervertebral foramen to converge into the brachial plexus. A few authors have also mentioned occasional contribution from the fifth cervical (C5) and second thoracic (T2) nerves.

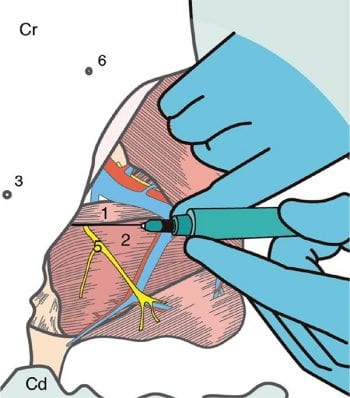

After placing the patient in lateral recumbency, with the thoracic limb to be blocked in the uppermost position, the scapula is shifted caudally until the transverse process of the C6 vertebra and the head of the first rib are easily palpated.

An index finger is placed on the ventral wing of the transverse process, which is an important anatomic landmark and covers the jugular groove to prevent inadvertent injection of local anaesthetic near the jugular vein, carotid artery and vagosympathetic trunk.

The ventral roots of C6 and C7 are relatively superficial and dorsal to the cranial and caudal margins of the transverse process, respectively.

The needle is inserted at a 45° angle to a horizontal plane, and directed dorsomedially towards both the cranial and caudal margins of the transverse process.

The ventral roots of C8 and T1 are located dorsally to the cranial and caudal margins of the head of the first rib, respectively. The placement of an index finger ventrally to the head of the first rib helps protect the thoracic inlet, and prevents inadvertent injection of local anaesthetic near major vessels and the vertebral ganglion, or within the pleural space.

The C8 ventral root nerve was targeted by directing the needle ventrally towards the cranial aspect of the head of the first rib. The T1 ventral root nerve was targeted by directing the needle ventrally and caudal to the rib, with the intention of placing the tip of the needle at the perceived level of the vertebral column.

For the purpose of being at the level of the intervertebral foramen, some authors have described a “walked off” technique in which the articular processes overlying the intervertebral foramen is identified with the tip of the needle, then the needle is “walked off” the cranial aspect of the process and directed 1.5cm further distally.

A modified technique for the nerve blockade of the C8 and T1 ventral roots has been described. The ventral roots of C8 and T1 converge 1cm to 2cm dorsally to the axillary artery and costochondral junction, along the cranial margin of the first rib. Therefore, the axillary artery and the costochondral junction of the first rib are identified, and the needle is directed along the cranial margin of the rib at either one or two sites.

This technique is useful for patients undergoing forelimb amputation, and surgical orthopaedic procedures of the shoulder and brachium.

A canine cadaveric study showed a low (33%) success rate to stain the four nerves, but a higher staining rate (66%) if only three of the four nerves were assessed (Hofmeister et al, 2007).

Although the paravertebral technique seems to be relatively easy, it is not exempt of complications. Clinicians should avoid performing the technique if the patient is obese or has heavy cervical musculature, due to the difficulty to palpate the anatomical landmarks. Also, patients with compromised respiratory function are not good candidates.

Anatomically, the phrenic nerve originates from the ventral roots of C5, C6 and C7, and runs medial to the brachial plexus. Although blockade of the phrenic nerve in conscious or anaesthetised dogs is either absent or showed not to affect the respiratory system, the fact of C6 and C7 ventral roots nerve blockade may produce hemidiaphragmatic paresis.

The patient is placed in lateral recumbency, with the thoracic limb to be blocked in the uppermost position.

Before performing the technique, it is mandatory to palpate the axillary artery at the level of the axillary region. Some authors have recommended applying slight pressure on the artery in this location, then moving the digit cranially until the pulse disappears, to ensure the correct location of the axillary artery in the thoracic region.

Then, the needle is inserted cranial to the first rib and lateral to the finger positioned over the axillary artery in the thoracic region near the costochondral junction.

This is an old technique that requires a large amount of anaesthetic solution, and it is most likely that structures proximal to the elbow are not anaesthetised.

A potential high risk exists of inadvertent puncture of the brachial artery and pneumothorax.

As a recommendation of the author, the measurement of the distance between the injection site and first rib may reduce intravascular and intrapleural injections, because the axillary vessels normally lie cranial to the first rib.

Also, it is relatively common to incompletely blockade the brachial plexus.

Radial nerve block

The patient is positioned in lateral recumbency, with the limb to be blocked in the uppermost position and the elbow flexed 90°.

The length of the humerus is measured along a line between the most prominent craniodorsal point of the greater tubercle and the most prominent point of the lateral epicondyle. The radial nerve tends to be located at the junction of the middle and distal thirds of the described line – slightly caudal to this line, and lying between the lateral head of the triceps and brachialis muscles.

A craniomedial pressure is applied with the thumb to cranially move the brachialis muscle away from the lateral head of the triceps.

The needle is inserted at a 45° angle, caudal to the thumb and perpendicular to the long axis of the humerus. The needle penetrates the lateral head of the triceps muscle and is directed until contacting the caudolateral aspect of the humeral shaft at the location of the radial nerve.

Ulnar, median and musculocutaneous nerve block

The dog is positioned in lateral recumbency, but the limb to be blocked is down, with the elbow flexed 90°. The uppermost limb has to be pulled caudally.

A line between the most prominent craniodorsal point of the greater tubercle and medial epicondyle determines the length of the medial aspect of the humerus. The ulnar, median and musculocutaneous (UMM) nerves are close to one another, approximately half the distance along this line from the medial epicondyle at the most proximal point at which the humeral shaft can be palpated. At this point, the humerus is palpated by digital pressure applied to the medial aspect of the limb.

The needle is inserted at a 45° angle from a caudal direction and perpendicular to the long axis of the humerus. The needle is directed caudally to the finger applying pressure, until the caudomedial aspect of the humerus is contacted.

The radial UMM nerve block is an easy technique to perform for procedures distal to the elbow, including the antebrachium (carpus, manus and digits).

Disadvantages exist, such as the need for an assistant (uppermost limb during UMM nerve block technique) and it is necessary to change the patient’s position. The risk for complications is lower, but inadvertent intravascular injection and nerve injury may be related.

Radial nerve block

The lateral and medial superficial branches of the radial nerve are blocked by inserting the needle between the first and second metacarpals, at the dorsomedial aspect of the carpus and proximal to the carpal joint. The needle is directed proximally.

Ulnar nerve block

The dorsal branch of the ulnar nerve runs laterally to the fifth metacarpal. The nerve is blocked by inserting the needle from the dorsolateral aspect of the carpus and distal to the carpal joint.

The superficial and deep palmar branches of the ulnar nerve run along the lateral aspect of the superficial digital flexor tendon at the palmar aspect of the paw. The needle is inserted lateral to the accessory carpal pad.

Median nerve block

The median nerve is blocked by inserting the needle medial to the superficial digital flexor tendon, and between the accessory carpal pad and first digital pad.

The described nerve blockade is a safe technique for the provision of analgesia for elective onychectomy and for procedures on the distal forelimb.

The dorsal cutaneous sensation is covered by the superficial branches of the radial nerve and the dorsal branch of the ulnar nerve. The palmar branches of the ulnar nerve and the median nerve are responsible for the palmar cutaneous sensation.

Also, the nerve blockade of the superficial and deep palmar branches of the ulnar nerve provides analgesia for the digital points.

The lumbar plexus is formed by the ventral roots of the third, fourth, fifth and sixth lumbar vertebrae (L3, L4, L5 and L6, respectively).

The ventral roots of the sixth and seventh lumbar (L7) – and first and second sacral vertebrae (S1 and S2, respectively) – converge to form the sacral plexus (Table 2).

The vertebral cavity (vertebral canal, spinal cavity or spinal canal) is formed by each vertebra from the foramen magnum to the sixth coccygeal vertebra. The dorsal part of the vertebral canal is formed by the vertebral laminae and the ligamentum flavum (interarcuate or yellow ligament).

The intervertebral pedicles and foramina conform the lateral walls of the canal. The floor of the vertebral canal is formed by the dorsal longitudinal ligament. The epidural space and intrathecal structures (spinal cord, meninges and CSF) are enclosed within the vertebral canal.

The spinal cord is a tubular structure of nervous tissue that extends from the medulla oblongata in the brainstem to the lumbar area of the vertebral column. The function of the spinal cord is the transmission of information from the brain to the peripheral nervous system. Nerve roots emerge from the spinal cord to merge into bilaterally symmetrical pairs of spinal nerves.

The meninges are three membranes responsible for the protection of the spinal cord:

Pia mater: the innermost membrane associated to the spinal cord. The subarachnoid space is the space surrounding the pia mater, and where the CSF remains. Also, the subarachnoid space contains the bunch of vessels that supply the spinal cord and separates the pia mater from the arachnoid mater.

Arachnoid mater: the middle protective membrane, which is closely adhered to the dura mater.

Dura mater: the outermost membrane. The dura mater contains the dorsoventral roots and spinal nerves, which leave the vertebral canal laterally through the intervertebral foramina.

The epidural space is the annular space that separates the boundaries of the vertebral canal and dura mater. The space is delimited dorsally by the ligamentum flavum, the capsule of the facet joints and laminae. The pedicles and the intervertebral foramina are the lateral walls.

Ventral delimitation is formed by the dorsal longitudinal ligament, vertebral bodies and discs. The epidural space contains fat (provides protection against mechanical trauma), the dural sac (contains the spinal cord and cauda equina), spinal nerves, blood vessels and connective tissue.

The animal is placed in sternal position over the table, with the pelvic limbs extended cranially. The patient may also be placed in lateral recumbency, depending on either the patient’s medical condition (fracture/s) or the clinician’s preference (heavy patient and difficult to position on the table).

Tuohy needles are recommended for epidural injections for the following reasons:

Clinicians should always wear sterile gloves when performing this technique. After clipping and surgically scrubbing, the epidural technique can be performed in a few areas:

Lumbosacral space: the most widely used in veterinary medicine. The space is located by palpation with the index finger of the spinous process of the L7 vertebra (it is recommended to also palpate L6 and S1 due to the difficulty to palpate L7). Both wings of the ilium are palpated with the thumb and middle finger. Then, the index finger moves caudally until a depression between the L7 and S1 vertebrae, which is the area for the lumbosacral puncture.

Sacrococcygeal or intercoccygeal: Space is localised by palpation of the anatomical landmarks.

The correct positioning of the needle is assessed by the following techniques:

Visualisation: visualisation of the needle head and the aspiration prior to the injection of the drugs is highly recommended. Presence of blood or CSF will indicate improper positioning or positioning in the subarachnoid space, respectively.

“Hanging drop”: once the skin has been pierced, and after removing the stylet, a drop (0.9% sodium chloride [NaCl], free of preservatives) is placed on the needle head. Once the interacted ligament has passed through and the bevel or tip of the needle is in the epidural space, the drop will be aspirated thanks to negative pressure.

Baraka: suitable to perform in dogs. After piercing the skin, the stylet is removed and the needle connected to an infusion system (0.9% NaCl, free of preservatives) elevated 60cm above the spinous or transverse process. When leaving the system open, the dripping will be slow (dorsal ligament) or null. After passing through the interacted ligament flavum, a continuous drip will confirm the bevel is in the epidural space.

Loss of resistance: a 5ml syringe with either a 1ml air bubble, or loaded with 0.9% NaCl and 1ml air, is connected to the epidural needle. As it is being passed through the tissues, the plunger of the syringe will be gently depressed. The air bubble will compress if it is outside the epidural space. However, a lack of resistance, compression and greater ease of injection will indicate correct positioning.

A successful epidural technique is reliable for any surgical procedure in the pelvic area.

Visualisation of the hub of the needle is mandatory to avoid administration, either in the subarachnoid space (consequences are sympathetic block, total spinal anaesthesia or death) or in the systemic circulation (high risk for local anaesthesia toxicity). Epidural should be avoided in the following situations:

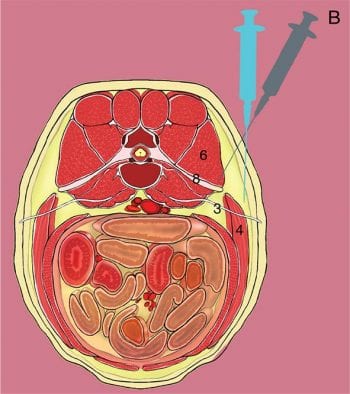

The patient is placed in lateral recumbency, with the pelvic limb to be blocked in the uppermost position. The end of the transverse process of the L7 vertebra is palpated with the index finger of the non-dominant hand.

The needle is inserted until contacting the end of the L7 transverse process. Then, the needle is “walked off”,and redirected laterally and advanced 1.5cm to 2cm distally (Figure 1).

Combination with other nerve blockade (femoral and/or obturator nerves) techniques can contribute to the analgesia for patients undergoing procedures involving the hip joint or femur.

The patient is placed in dorsal recumbency. Maximal abduction position (the femur is at 90° in relation to the vertebral column) of the pelvic limb to be blocked is required.

The location of the depression – between the adductor and pectineus muscles – is palpated with the finger of the non‑dominant hand. The needle is inserted at 30° in relation to the table, then advanced up to 3cm (Figure 2).

Although the obturator nerve has mainly motor innervation for the adductor (medial) muscles, few authors have described a sensory innervation for the hip joint and stifle in dogs.

The patient is placed in dorsal recumbency. As aforementioned for the obturator nerve block, a maximal abduction position (the femur is at 90° in relation to the vertebral column) of the pelvic limb to be blocked is required. Three techniques are described in the veterinary literature:

The saphenous nerve blockade is useful for procedures for the cranial and medial aspect of the stifle.

Additionally, a combination with a sciatic nerve block will have the advantage of preserving the motor function of the quadriceps muscle.

The patient is placed in lateral recumbency, with the leg to be blocked positioned uppermost and extended naturally.

The needle is inserted distally, a third of the distance along an imaginary line between the femoral greater trochanter and ischiatic tuberosity.

The combined use of femoral and sciatic nerve blockade techniques is reliable in patients undergoing stifle surgery.

The patient is placed in lateral recumbency, with the pelvic limb to be blocked in the uppermost position.

Two techniques are described in veterinary literature:

The needle is inserted between the lateral and medial heads of the gastrocnemius to block the tibial nerve. Also, the tibial nerve blockade can be performed by inserting the needle below the stifle, and between the superficial flexor tendons and the long digital extensor tendon distal to the lateral saphenous vein. The common peroneal nerve is blocked by inserting the needle dorsal and posterior to the head of the fibula.

The clinician places the thumb of his or her non‑dominant hand caudally in the groove between the biceps femoris and semimembranosus/semitendinosus muscles. The rest of the fingers grasp and lift the cranial edge of the biceps femoris muscle, the body of the biceps femoris muscle at the midpoint between the patella and greater trochanter. The thumb is caudocranially advanced into the groove until palpation of the caudal aspect of the femur. The needle is injected perpendicular to the long axis of the femur and parallel to the table. The needle is then advanced caudocranially adjacent to the thumb until the caudal aspect of the femur is contacted. Finally, the needle is walked off 1cm.

Both nerve blockade techniques contribute to analgesia in patients undergoing procedures involving the stifle joint, tarsus and digits. A small risk exists of vascular puncture.