4 Feb 2019

Matthew Best discusses thoracic respiratory disease, including immune-mediated and infectious aetiologies.

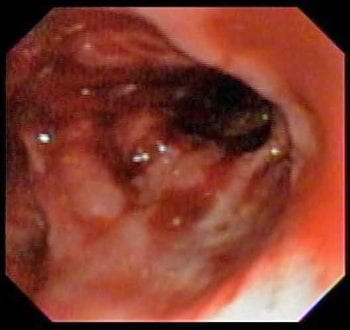

Figure 1a. This object was removed endoscopically and despite a visibly marked airway injury after removal, the dog’s clinical signs resolved almost immediately.

Allergic, immune-mediated, hypersensitivity and infectious airway diseases of the dog and cat are a varied and very common cause for patients to present to a vet. The clinical signs and significance of the disease vary greatly depending on the location and severity of the inflammation. While airway diseases account for the majority of cases, significant inflammatory diseases also exist of the parenchyma, interstitium and pleura for the clinician to be aware of. Correct diagnosis is key and careful attention to the presenting signs will often help direct the appropriate tests for each patient. Symptomatic treatment, such as oxygen therapy, sedation and bronchodilators can be useful for acute and chronic management, but it is very important not to neglect treatment of the primary disease, whether that is with anti-inflammatories/immunosuppressants or antimicrobials.

The respiratory system is physiologically incredible in dogs and cats, with a large built-in redundancy. Many inflammatory diseases exist, both acute/chronic and infectious/sterile, which can affect this system, each of which tends to localise to a specific part of the respiratory anatomy.

Clinical signs can range from mild and irritating, to severe and life-threatening. It is important to note, if the respiratory reserve is compromised to the point of respiratory difficulty, the disease must be highly advanced and patient status should be considered critical.

This article works through the respiratory system – starting in the airways and ending in the pleural space. Along the way, the author discusses the main inflammatory diseases occurring at each site in dogs and cats, including typical clinical signs, appropriate diagnostic testing and treatment approaches, with some discussion of their evidence base.

Significant diseases:

In dogs, inflammatory disease of the airways most significantly cause coughing. The duration of clinical signs and the presence of other concurrent clinical signs, such as fever in kennel cough, can be very useful at narrowing down the differentials. Chronic airway disease can sometimes cause pulmonary hypertension and alterations to vagal tone, which can be seen as syncope – cough and drop.

In cats, the clinical signs can be more diverse, with acute feline asthma, an allergic airway disease, presenting with bronchoconstriction – causing increased respiratory effort (expiratory push) and dyspnoea. In chronic asthma and feline bronchitis – a hypersensitivity disease – coughing is the prominent feature.

A thorough history-taking and examination are important for all respiratory diseases. Clues from the history might include seasonality or fluctuation with environmental changes. On examination, observation of breathing, auscultation of the chest and testing tracheal sensitivity can all be helpful.

As we rarely perform functional testing of the respiratory system in veterinary medicine, the diagnostics hinge around imaging for structural disease and sampling to define the nature of any underlying inflammation.

Three-view thoracic radiographs are an excellent initial test at relatively low cost and widely available. Where appropriate, thoracic CT should also be considered as an alternative option, which is significantly more sensitive for structural disease. The purpose of imaging is to look for features of airway disease, such as a bronchial pattern, hyperinflation (feline asthma only) or right-sided cardiomegaly, as well as to exclude other potential causes of respiratory signs, such as pneumonia, neoplasia, congestive heart failure and pleural effusion. Where appropriate, cardiac disease can also be assessed with echocardiography or biomarkers.

The next test for structural disease is bronchoscopy. This method allows visualisation of the airways, while features of airway inflammation can be seen, such as irregular mucosa and mucus accumulation. However, the main purposes of bronchoscopy in inflammatory airway disease are to exclude other structural disease, including airway collapse, foreign material (Figure 1) and mass lesions, and to facilitate airway sampling. Be aware of the risk of complications with bronchoscopy, particularly in asthmatic cats1,2. The administration of terbutaline prior to the procedure might help reduce the risk of bronchospasm1.

Sampling the airways – whether by tracheal/transtracheal wash or bronchoalveolar lavage – is key to the ultimate diagnosis of all airway diseases. This test allows the demonstration of airway inflammation, the identification of prominent cell type (neutrophil in bronchitis/tracheitis of all types and eosinophils in asthma) and assessment for infectious disease through microscopy, culture and PCR panels.

In all cases of inflammatory airway disease the treatment has three goals:

Definitive treatment requires improving the underlying stimulus of inflammation and involves treating any infection present, where possible, and reducing environmental exposure to any triggers (hypoallergenic bedding, air conditioning filters, regular vacuuming, reducing smoke exposure, reducing exposure to other irritants – such as diffusers and cleaning products – weight loss, preventing excessive barking or switching from a collar to a harness).

Anti-inflammatory therapy is indicated in all cases of non-infectious airway inflammation, as chronic inflammation will eventually cause irreparable airway remodelling, such as bronchiectasis, even if the symptoms were being relatively well-controlled. The mainstay is corticosteroids, either orally or inhalational. While the latter is off-label, the benefit of reduced systemic exposure3 is clear, particularly where weight gain is undesirable. For the same reason the lowest effective dose should be used. It should be noted that in veterinary medicine we very rarely monitor for subclinical inflammation, which has been well demonstrated in human medicine to cause airway remodelling in asymptomatic patients4.

Symptomatic treatment can be life-saving in acute crises and can also reduce inflammation by breaking the cough-inflammation cycle. In cats with respiratory distress, acute bronchodilation with terbutaline or inhaled salbutamol is indicated alongside sedation – for example, butorphanol.

Owners can have bronchodilators on hand for home use, but regular maintenance use is not encouraged as the S-enantiomer of salbutamol can be proinflammatory with chronic use5, and chronic use of terbutaline is likely to result in tolerance.

For chronic coughing, antitussive agents can produce marked improvements in quality of life for dogs and cats, and many owners will also thank you for a good night’s sleep where nocturnal coughing is a problem. Opiates compose the mainstay of this therapy, with (off-label) oral diphenoxylate the most potent option, when this is available, but codeine is also effective. Where required, and owners can comply, low-dose parenteral butorphanol can be extremely effective.

Significant diseases:

Clinical signs of parenchymal inflammatory disease are frequently non-specific. In severe cases, increased respiratory rate and effort can be seen. This can be accompanied by secondary signs, including cough, pyrexia and lethargy, but these are not always present.

Classic auscultation findings are crackles, but take care as these are not always clearly audible – particularly where significant lung consolidation is present – and are not specific to paren-chymal disease.

Blood testing can show non-specific changes, such as increased or decreased neutrophils with a left shift or increases in C-reactive protein (CRP), which are commonly seen in cases with severe pneumonia6. Angiostrongylus antigen tests and faecal parasitology can also be useful where parasitic inflammatory disease is possible.

Thoracic radiographs can be very helpful with parenchymal disease classically showing alveolar pattern. The distribution of this pattern can also be helpful – for example, aspiration pneumonia typically showing a ventral distribution and most commonly affecting the right-middle lung lobe7.

Thoracic ultrasound can also be a very useful test – being easy to perform, even in unstable patients, and providing immediate information. In broad terms, lung surface ultrasound can show “dry” or “wet” lung. In dry lung, horizontal A-lines dominate, while, in wet lung, increasing numbers of vertical B-lines (also called lung rockets) appear with consolidated lung having an appearance not dissimilar to liver (Figure 2)8. As with radiographs, both the appearance and distribution of these patterns are useful8.

Thoracic CT can provide the same information as the aforementioned modalities, but with a higher sensitivity and a better ability to detect underlying causes, such as migrating foreign bodies and bronchiectasis9.

Ultimately, sampling of the parenchymal fluid is required to make a definitive diagnosis. Typically, sampling is achieved through a bronchoalveolar lavage, but lung aspiration should also be

considered in unstable patients or those where costs limit the diagnostic approach. Any samples collected should be examined cytologically for the presence of inflammation, foreign material and microorganisms. Where microorganisms are on the differential list, bacterial culture is indicated.

The recent explosion of available PCR options has also opened the door to diagnoses of difficult-to-culture bacteria, such as mycoplasma and Bordetella, as well as non-bacterial organisms, such as helminths, protozoa, viruses and Pneumocystis.

The approach to treatment is very variable and depends on the underlying disease. In most cases the appropriate therapy is targeted at the underlying cause, which usually involves antimicrobials, while providing supportive care in the form of oxygen therapy, nebulisation, fluid therapy and time.

Historically, the treatment recommendations for pneumonia were to treat for four to six weeks10. This is at odds with human guidelines for pneumonia, where low severity pneumonia is treated for five days with amoxicillin and high severity pneumonia is treated for 7 to 10 days11. The use of CRP to guide the duration of antibiotic use might be a comfortable alternative for veterinary medicine12.

Significant diseases:

Interstitial inflammatory diseases are very rare in the dog and cat, with the exception of eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy.

Eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy can affect any dog, but primarily affects adult dogs, particularly arctic breeds and Rottweilers. Most patients present with coughing and frequently a peripheral eosinophilia exists to further increase suspicion.

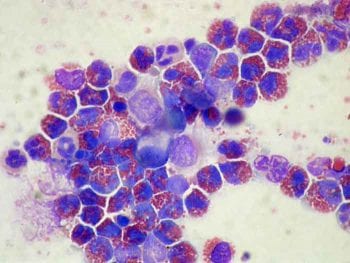

Radiographs can show an interstitial or nodular pattern. The final diagnosis relies on demonstrating an eosinophilic airway inflammation (Figure 3), while excluding fungal disease, heartworm, lungworm or neoplasia.

Immunosuppressive corticosteroids are an effective treatment with a good response expected in most dogs13.

Significant diseases:

Pyothorax has fairly distinctive clinical signs, with inspiratory dyspnoea and pyrexia highly suggestive of this condition (though not always present). In cats presenting with respiratory compromise and pyrexia, this should be the main differential14. Signs can be chronic and careful history taking might reveal a reducing appetite over time.

Radiographs, sonography or thoracocentesis will all reveal a pleural effusion. Cytology and culture of the fluid will confirm a pyothorax.

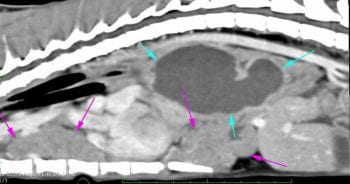

Advanced imaging should be considered to look for foreign body tracts or penetrating wounds, as well as to rule out abscess formation, which would make a good response to medical management unlikely (Figure 4).

Treatment options vary with the severity of signs and likelihood of a foreign body or abscess. Single drainage and oral antibiotics have been shown to be effective, but some patients require more intensive therapy, such as chest drain placement and lavage, or surgical exploration and lavage15.

Potentiated amoxicillin is a reasonable initial choice while cultures are pending. The course should be continued for four to six weeks – and beyond demonstrated resolution of the effusion.