26 Aug 2022

Katie McCallum BVM&S, PGCertSAM, AFHEA, DipECIM-CA, MRCVS outlines the clinical signs of cobalamin deficiency and shares a unique example of a patient with this condition.

Patient before (left) and after (right) cobalamin supplementation.

Cobalamin, or vitamin B12 , is a key water-soluble vitamin responsible for multiple functions in the body. As an essential enzyme co-factor, it is involved with cellular energy production, DNA synthesis, nervous system function, amino acid and lipid metabolism, and in erythrocytosis.

Cobalamin is found in foods of animal origin and, when ingested, forms a complex with intrinsic factor (IF), released from the exocrine pancreas, in the duodenum. This complex is then absorbed via cubam receptor-mediated endocytosis, in the ileum.

It is also now thought that in dogs and cats, 1% of dietary cobalamin is absorbed by passive diffusion, throughout the whole gastrointestinal tract1,2. This route of absorption is independent of IF.

Hypocobalaminaemia is becoming increasingly recognised in small animal medicine, as it can be caused by a multitude of diseases.

Disorders that alter either intestinal cobalamin concentrations, IF production or the uptake of cobalamin-IF-complex will result in low serum cobalamin concentration.

The specific diseases include exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI), dysbiosis, chronic enteropathies, intestinal neoplasia and inherited disorders of cobalamin absorption1,3.

Breeds in which these inherited disorders can be seen include the border collie, giant schnauzer, Shar Pei and beagle3. It is, therefore, recommended to monitor serum cobalamin concentration in patients with EPI and chronic gastrointestinal disease.

Patients with hypocobalaminaemia often do not respond to treatment of their underlying GI disorder if low cobalamin concentrations are not corrected4. This is due to the effects of hypocobalaminaemia on mucosal inflammation and villous atrophy3.

The clinical signs of hypocobalaminaemia in dogs and cats can be vague and non-specific, including:

Various studies have investigated the prevalence of low B12 concentrations in different disease processes.

Furthermore, hypocobalaminaemia has been shown to be a negative prognostic indicator in dogs with EPI and chronic enteropathies8,9.

It is recommended to supplement B12 in patients with associated clinical signs and low-normal cobalamin concentrations (250ng/L to 350ng/L)10,11.

Oral dosing of vitamin B12 has been found to be very effective at increasing cobalamin concentrations in dogs and cats1,2,12. One recent study, in dogs with EPI specifically, where a lack of IF synthesis and secretion was found, demonstrated that oral supplementation could correct hypocobalaminaemia13.

Some evidence suggests oral supplementation may be more effective in the long-term, with significantly higher cobalamin concentrations noted following 90 days of treatment, compared to parenteral administration1.

Studies have shown that the effective dose of cobalamin is1,2,12-14:

A one-year-old, male neutered border collie was referred to The Queen’s Veterinary School Hospital for investigation into an eight-month history of failure to gain weight, lethargy and intermittent gastrointestinal symptoms.

Leukopenia, borderline anaemia and hypocobalaminaemia (less than 150ng/L; 200–) were identified prior to referral. Faecal analysis and abdominal ultrasound were both unremarkable, with clinical improvement seen on a low-fat diet, alongside metronidazole. No cobalamin or multivitamin supplementation was given prior to referral.

Haematology was unremarkable. Urinalysis showed a mild proteinuria, bilirubinuria and haematuria with a negative culture. Cobalamin was within the normal reference range (286ng/L).

On biochemistry, hypoproteinaemia and hypocholesterolaemia were noted, alongside elevated alkaline phosphatase (211IU/L; normal 26IU/L to 107IU/L) and 1,2-o-dilauryl-rac-glycero-3-glutaric acid lipase (525IU/L; 0IU/L to 200IU/L).

The trypsin-like immunoreactivity result was above 50μg/L, which is consistent with pancreatic inflammation.

Abdominal ultrasound also identified changes within the pancreas that were suggestive of pancreatic inflammation (Figure 1).

The dog was hospitalised and treated for pancreatitis with maropitant, buprenorphine, ranitidine, and paracetamol.

After six days of treatment the dog was discharged, and cobalamin was re-evaluated four weeks after initial presentation. At this point, despite clinical improvement, the serum concentration was subnormal (less than 150ng/L).

A urine sample was submitted to the metabolic genetic screening laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania for a methylmalonic acid (MMA) spot test, which was positive – consistent with methylmalonic aciduria, which is suggestive of a cobalamin deficiency at the cellular level.

Hypocobalaminaemia was treated with 0.5mg cyanocobalamin orally once daily. A DNA test (AHT, UK) showed that the patient was homozygous for the genetic mutation of the CUBN gene (a component of the cubam receptor responsible for ileal cobalamin absorption), consistent with a diagnosis of Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome.

Serum cobalamin concentration was remeasured 730 days after starting supplementation and found to be supranormal (974ng/L). Twenty-seven months after initial presentation, the dog was clinically well, with no recurrence of clinical signs.

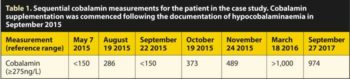

Table 1 shows the cobalamin measurements in the patient over the course of investigations and treatment.

This is the first report of pancreatitis associated with hereditary selective cobalamin malabsorption in a dog. In this case, the cobalamin concentration was initially documented as low by the referring vet, but was found to be normal at referral presentation.

Serum cobalamin concentration does not always correlate with body stores, and dogs with low-normal serum cobalamin and concurrently increased serum MMA have been previously reported, suggesting a cobalamin deficiency at the cellular level.

Hereditary cobalamin deficiency was confirmed in this case with the patient homozygous for mutation in the CUBN gene. The carrier frequency of this mutation in border collies is 6.2%. This case responded well to oral cobalamin supplementation.