5 Mar 2024

Sarah Caney provides an update regarding this syndrome, including ways of ensuring clients are on board.

Figure 1. Weight loss is the most common clinical sign associated with hyperthyroidism, and this diagnosis should be considered in any cat with unexplained weight loss, even if body condition is normal or overweight on examination.

One of the most common clinical signs of hyperthyroidism is weight loss, often in spite of a normal or even increased appetite (Table 1).

| Table 1. Clinical findings in cats with hyperthyroidism, listed in approximate order of decreasing frequency | |

|---|---|

| Clinical sign |

Approximate frequency, percentage of cats (Baral and Peterson, 2012) |

| Weight loss | 88 |

| Polyphagia | 49 |

| Vomiting | 44 |

| Polyuria/polydipsia | 36 |

| Increased activity | 31 |

| Decreased appetite | 16 |

| Diarrhoea | 15 |

| Decreased activity | 12 |

| Weakness | 12 |

| Dyspnoea | 10 |

| Panting | 9 |

| Large faecal volume | 8 |

| Anorexia | 7 |

| Physical examination findings | |

| Large thyroid gland | 83 |

| Thin | 65 |

| Heart murmur | 54 |

| Tachycardia | 42 |

| Gallop rhythm | 15 |

| Hyperkinesis | 15 |

| Aggressiveness | 10 |

| Unkempt hair coat (Figure 1) | 9 |

| Increased nail growth | 6 |

| Alopecia | 3 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2 |

| Ventral neck flexion | 1 |

Signs are generally most obvious in cats that have been suffering with the illness for longer and in those that have concurrent illnesses.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is the most common concurrent illness, estimated to affect up to one-third of patients (Carney et al, 2016). Many cats with hyperthyroidism can appear “healthy” to an owner – polyphagia and hyperactivity can be interpreted as a cat with “joie de vivre”, and weight loss often passes unnoticed.

Key findings on physical examination include weight loss, presence of a goitre (unilateral or bilateral palpable thyroid gland) and cardiac auscultation abnormalities such as tachycardia, new heart murmur and gallop rhythm (Figure 1).

In most cats, the diagnosis can be confirmed by measuring resting serum total thyroxine (T4) levels. Routine serum biochemistry often reveals elevated levels of liver enzymes (alanine aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase), leucocytosis, eosinopenia and erythrocytosis. Mild hypokalaemia and/or hyperphosphataemia are seen in a small number of patients.

Occasionally, a normal total T4 result is received in a cat suspected of having hyperthyroidism. This is especially common in cats that have concurrent disease, such as CKD, resulting in suppression of total T4 levels: the so-called sick euthyroid phenomenon.

Repeat total T4 testing at a reference laboratory and free T4 and thyroid-stimulating hormone assessment (TSH) can be helpful. Cats suffering from hyperthyroidism typically have elevated free and total T4, and low or undetectable levels of TSH (Peterson et al, 2015).

Diagnosis of hyperthyroidism is rarely an emergency, as this is a slowly progressive illness; therefore, if in doubt of the diagnosis, repeating assessment (a “watch and wait” approach) is sensible rather than treating the cat.

Two broad categories of treatment exist: potentially curative, permanent options such as radioiodine and surgical thyroidectomy, and reversible options, such as an iodine-restricted food or medication. Curative options are favoured by the author, where possible – especially when hyperthyroidism is diagnosed in a relatively young and otherwise healthy cat. Patients should be screened for presence of systemic hypertension, which is estimated to be present in 10% to 20% of cats suffering from hyperthyroidism.

Veterinary-licensed antithyroid medications include tablet forms of thiamazole (also known as methimazole), liquid thiamazole preparations and carbimazole sustained release tablets. These products block production of the thyroid hormones and, therefore, symptomatically manage the hyperthyroidism.

Lifelong treatment is required unless a curative treatment such as surgery or radioiodine is subsequently pursued. In the long term, difficulties with owner and patient compliance may reduce the overall success of this treatment modality. Nevertheless, medical treatment is popular – not least since it is a reversible treatment, which can be of benefit when stabilising patients with concurrent CKD.

Ideally, a dose resulting in reduction of total T4 levels to the lower half of the reference range is aimed for. Total T4 levels should be checked two to three weeks after starting treatment or changing the dose (Daminet et al, 2014; Carney et al, 2016).

Transdermal methimazole gel is also available in the UK via a number of specials laboratories. Transdermal methimazole is not a veterinary-licensed preparation, but can be used under cascade regulations where appropriate. The gel is usually applied to the inside of the pinna (a hairless area); carers should wear gloves and avoid direct contact with the gel.

The medication is absorbed through the skin and into the bloodstream. Transdermal antithyroid medications can take longer to be effective than the oral forms, and it is typical for patients to need a higher dose of medication – typically double the oral dose.

Side effects have been reported with oral and transdermal administration of thioureylenes. Around 10% to 20% of patients may suffer from temporary and manageable side effects, including lethargy, inappetence, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting. In most cats with these side effects, the clinical signs are mild and only last a few days. In some cats, the side effects are more severe and may necessitate stopping treatment, or having a treatment “holiday”. Starting treatment at a low dose before gradually increasing this, as needed, helps minimise the occurrence and severity of side effects.

Severe side effects may be seen in up to 5% of treated cats and necessitate withdrawal of therapy before an alternative treatment is started. Side effects most commonly develop in the first few months of therapy and include:

Production of thyroid hormone requires iodine molecules; therefore, limiting the amount of iodine fed reduces the amount of thyroid hormone produced and released by the thyroid gland.

As with medical management, lifelong treatment (with 100% compliance) is required unless a curative treatment is subsequently pursued. Patient and owner compliance is essential to the success of this approach – even small deviations from the prescribed feeding can allow “escape” of thyroid control. Unlike medical treatment, no “drug-related” side effects occur to worry about, but compliance to the food may be an issue – especially if using this treatment long term.

The food is phosphate restricted and moderate in protein, making it an acceptable nutrition for cats with mild to moderate CKD (but not recommended for cats in International Renal Interest Society [IRIS] stages three and four CKD).

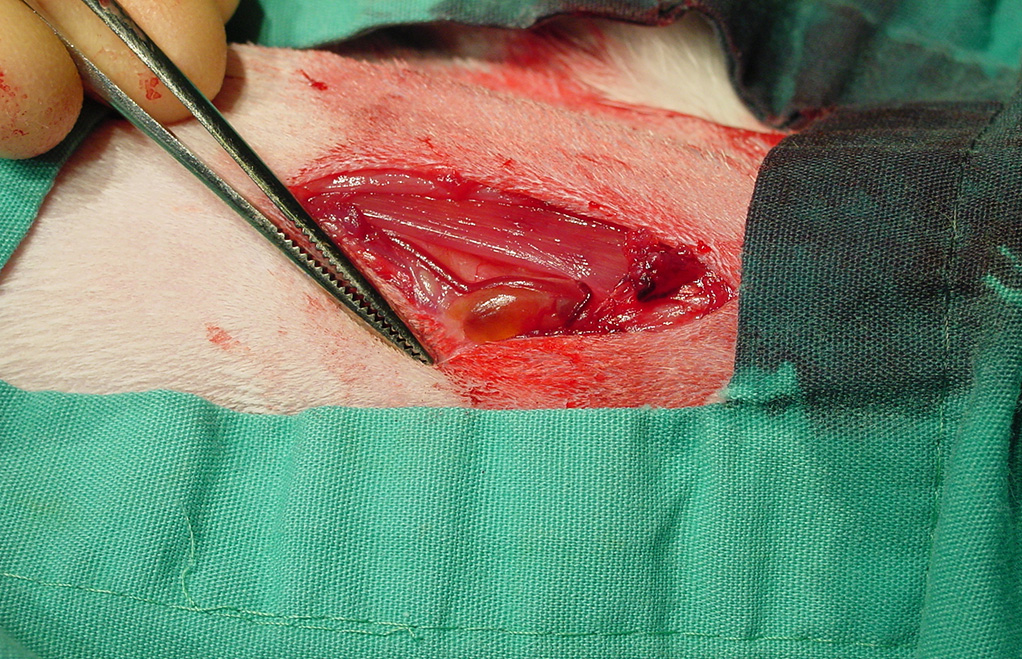

Surgical thyroidectomy is a potentially curative treatment with the disadvantage of requiring general anaesthesia (which may be contraindicated in some patients), and is only suitable for those cases with easily accessible hyperfunctional thyroid tissue (Figure 2).

Up to 20% of patients may have ectopic hyperfunctional thyroid tissue, and this is commonly located in the anterior thorax – not an area suited to straightforward thyroidectomy (Harvey et al, 2009). Pre-surgical stabilisation with antithyroid medication or an iodine-restricted food is recommended. In routine cases, side effects of thyroidectomy, such as damage to the parathyroid glands resulting in hypocalcaemia, are possible. Recurrence of hyperthyroidism post-thyroidectomy was reported in more than 40% of cases in a recent case series (Covey et al, 2019).

Radioiodine treatment is administered by SC injection or oral capsule. The radioactive iodine targets the abnormal thyroid tissue, typically resulting in a 95% success rate. Published studies have so far shown that the best long-term prognosis for treatment of hyperthyroidism is achieved with radioiodine.

Deterioration in renal function associated with treatment of hyperthyroidism

All treatments for hyperthyroidism have the potential to worsen kidney function. This is because the hyperthyroid condition increases renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate. When the hyperthyroidism is treated, the increased blood flow to the kidneys decreases.

For many hyperthyroid cats, this return to normality is not associated with kidney problems. However, in a proportion of patients, this reduction in blood flow has the potential to “unmask” kidney disease that was not previously known about and to worsen pre-existing kidney disease. Unfortunately, no guaranteed method exists to predict which cats will suffer renal problems following treatment of their thyroid disease, although symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) assessment may be of some use.

A study by Peterson et al (2018) showed that while non-azotaemic cats with elevated pre-treatment SDMA were more likely to develop renal complications following stabilisation of their thyroid disease, unfortunately, having a normal pre-treatment SDMA was no guarantee of protection from renal complications. In other words, assessment of pre-treatment SDMA had a poor sensitivity, but high specificity for predicting azotaemia following treatment of hyperthyroidism. Hyperthyroidism is damaging to the kidneys, so optimal management of the hyperthyroidism is desirable, where at all possible. Typically, it is only cats with very serious CKD (for example, IRIS stage four, creatinine level more than 440mmol/L) where optimal management of hyperthyroidism proves difficult, or impossible, without inducing a clinical and laboratory deterioration in renal function.

Many carers will have some awareness of thyroid disease, since this is not uncommon in people.

Hypothyroidism is more common than hyperthyroidism in people, estimated to affect up to five of the population, with females and individuals older than 60 years over represented. Hyperthyroidism affects a smaller proportion of individuals, but current treatments are similar in principle to those offered by veterinarians: anti-thyroid medications, radioiodine and surgical thyroidectomy. A useful starting point for client discussions can, therefore, be thyroid disease in people.

Successful compliance depends on concordance – shared decision making – so that a suitable management plan can be put in place. Discussions should incorporate the following.

| Table 2. Advantages and disadvantages of each of the management options for hyperthyroidism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical management: thioureylenes (methimazole, carbimazole) | Nutritional management: iodine-restricted diet | Surgical thyroidectomy | Radioiodine | |

| Advantages | • Readily available • Initially less expensive than the curative treatment options: cost spread over the course of treatment • Fairly rapid onset of action – most patients euthyroid within a few weeks • Most cats suffer no side effects of treatment, even with very long-term use • Can be titrated or withdrawn – especially helpful in cats that have concurrent chronic kidney disease • Very helpful in stabilising a patient in preparation for surgical treatment or while awaiting radioiodine • No hospitalisation, sedation or anaesthesia is required • Hypothyroidism is rare with medical treatment and can be easily corrected by reducing the dose of medication |

• Readily available • Initially less expensive than the curative treatment options: cost spread over the course of treatment • No side effects reported (other than reduced renal function, which can occur with any treatment for hyperthyroidism) • No need for anti-thyroid medication in those cats that accept the food • Reversible – especially an advantage in cats with concurrent kidney disease where any treatment for hyperthyroidism can cause a worsening in their kidney function • Very helpful in stabilising a patient in preparation for surgical treatment or while it is awaiting radioiodine • No hospitalisation, sedation or anaesthesia is required • Easier to administer than medication? |

• Available in most practices • Potentially curative with no further requirement for anti-thyroid medication • Straightforward surgery in many patients • Rapidly effective • Short hospitalisation period (typically a few days) |

• High cure rate (95%) with no further requirement for anti-thyroid medication • No anaesthesia required • All abnormal thyroid tissue is treated, regardless of its location in the body (that is, ectopic thyroid tissue treated, too) • Safe to adjacent structures such as the parathyroid glands • Recurrence of disease is very rare • Side effects are rare • The only effective treatment for thyroid carcinomas (higher dose required) |

| Disadvantages | • Side effects can be serious in some patients and may require withdrawal of medication • Regular monitoring, including blood tests, is recommended so that any side effects can be identified and treated quickly • The medication does not cure the condition, so treatment is required for the rest of the cat’s life • Treatment monitoring is required to ensure that the correct dose of medication is being given – over time, the required dose of medication may change • Some studies have suggested that compliance with long-term medical treatment can be a problem, making medical management less effective in the long term compared to curative treatment options such as radioiodine • Hyperthyroid cats can be difficult to medicate, so long-term treatment can be hard work • Very occasionally, some cats are resistant to the thioureylene drugs, meaning they may need very high doses or an alternative treatment to control their illness • The cost of medication and check ups can be more expensive than curative options in the long term |

• Successful management depends on 100% compliance to the food • It can take up to 12 weeks to achieve euthyroidism (slower than anti-thyroid medications) • The food does not cure the condition, so treatment is required for the rest of the cat’s life • Not ideal for multi-cat households (supplementation of healthy cats recommended if it is not possible to feed their normal food) • Many treats and some nutritional supplements contain iodine, and are, therefore, “banned”; cats that are keen hunters may have poor control if they eat their prey • Some water sources may contain iodine which could affect efficacy • Long-term compliance may be an issue? • Some cats will not accept the food • Some cats do not fully respond to the food • Not an ideal food for cats in International Renal Interest Society stage three or four kidney disease • The cost of food and check ups can be more expensive than curative options in the long term |

• Requires general anaesthesia • Technically more difficult than other treatments • Only possible if the thyroid nodule is accessible to surgical removal (most cases) • Can be expensive • Complications – especially to the parathyroid glands – are possible and can be life-threatening (hypoparathyroidism) • Recurrence possible if not all of the abnormal tissue is removed • Occasional permanent hypothyroidism, requiring supplemental thyroid hormones • Long-term success is relatively poor compared to radioiodine |

• Special facilities required – not routinely available • Human health and safety considerations require separate hospitalisation of patients for a period following treatment (typically one to two weeks) • While hospitalised, other treatments may not be possible, so radioiodine is usually only suitable for reasonably well hyperthyroid cats • Can be very expensive • It may take several months for euthyroidism to be achieved • Occasionally (around 5% of cases), a second treatment with radioiodine is required to achieve euthyroidism • Occasional permanent hypothyroidism, requiring supplemental thyroid hormones |

Ideally, discussions are non-judgemental and aim to find the best solution for the client and cat’s concerns (Panel 1); therefore, the ideal management protocol will differ according to the individual situation. A relationship-centred, collaborative approach is likely to be more successful (Kanji et al, 2012), and offering a range of treatment options from intense or expensive to a less expensive or less intense choice has been recommended in recent studies of other chronic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus (Niessen et al, 2017).

Regular check ups are important – especially in those cats managed with reversible options. The aim of check ups is to ensure that therapy is optimal without any significant side effects. Suitable protocols for check ups are covered elsewhere (Daminet et al, 2014; Carney et al, 2016).

Iatrogenic hypothyroidism is an important adverse effect to monitor for in all cats receiving treatment for their hyperthyroidism, since it is associated with a worse prognosis.

In general, the prognosis for management of hyperthyroidism is very good, depending on the severity of the disease and presence of other concurrent illnesses such as CKD.

For the long-term care of hyperthyroid cats, check ups are really important and, for those cats receiving reversible options, regular blood tests are necessary to ensure that the hyperthyroidism is under control and the cat is not suffering from any side effects.

Most cats do very well when being treated for hyperthyroidism, and the sooner it is diagnosed, the better the outcome generally.