2 Jan 2024

Andy Moores describes some of the procedures available for treating this condition in cats and dogs.

Hip dysplasia is one of the most commonly diagnosed orthopaedic conditions in dogs, if not the most common. It can result in a wide spectrum of clinical signs from those dogs that are seemingly unaffected by their hips through to dogs with severe and chronic hip pain that significantly impacts quality of life.

Most dogs will be managed medically, but several surgical options exist for dogs (and also cats). So, what are the surgical options and when do we consider them?

We should firstly mention some historic options. Older members of the profession may remember pectineal myectomy and osteotomies of the proximal femur (intertrochanteric osteotomy or neck lengthening osteotomy) being described to manage hip dysplasia. These are no longer considered effective options and are not advised.

The options that do have merit can be split into two categories: those that are considered “prophylactic” and those that are “salvage” surgeries.

Juvenile pubic symphysiodesis (JPS) is the surgical fusion of the pubic symphysis in young puppies, such that continued growth of the pelvis results in ventrolateral rotation of each acetabulum and improved “capture” of a dysplastic hip. This is usually achieved by electrosurgery ablation of the symphysis. It is a simple and quick procedure with minimal aftercare requirements. The limiting factor for widespread use of JPS is that it must be performed in puppies between 12 and 16 weeks of age (up to 22 weeks in giant breeds) to be effective. These puppies will not be symptomatic at this age, and so unless at-risk puppies are proactively screened at a young age, they will miss the window of opportunity for the procedure.

Screening itself is also problematic. At such a young age, conventional radiographic screening may not identify hip dysplasia. On the ventrodorsal hip radiograph, extension of a dysplastic (loose) hip can result in tightening of the joint capsule and medialisation of the femoral head into the acetabulum; therefore, giving the appearance of a normal hip. The distraction index calculated from distraction radiographs (PennHip scheme) is a reliable assessment tool, but the technique as traditionally described requires manual positioning of the patient during the x-ray exposure, which is not permitted in the UK.

Hands-free variations of the technique have been described, but not widely adopted. Many surgeons performing JPS will, therefore, rely on manual tests such as the Ortolani sign to identify hip laxity and, therefore, screen for candidates (you can learn how to perform an Ortolani test via tinyurl.com/dogortolani).

Regardless of these difficulties, with appropriate case selection JPS can be an effective technique to improve the stability of a dysplastic hip and mitigate the progression of osteoarthritis (OA), and screening is probably sensible for puppies of at-risk breeds (especially if the parent hip scores are poor or unknown) and/or those with a history of hip dysplasia in close family relatives.

It may not be desirable to neuter puppies at the same time as JPS, but they should be neutered when they are older and all owners requesting JPS should be advised of this.

Triple pelvic osteotomy (TPO) involves osteotomies of the ilium, the pubis and the ischium, which allow the acetabulum to be rotated ventrolaterally to improve femoral head capture. The rotated bone segment is stabilised with a specialist bone plate on the ilium.

TPO has been largely superseded by double pelvic osteotomy (DPO), which is very similar, but does not include the ischial osteotomy (and, therefore, does not destabilise the acetabular segment as much as TPO).

Both techniques require careful case selection to be effective. They should be performed before the development of secondary osseous changes affecting the hip, and this limits their use to juvenile dogs. Most candidates are five to 10 months of age, but this is not a hard and fast rule.

TPO and DPO are major orthopaedic procedures with a risk of potentially serious complications. Most surgeons would, therefore, reserve surgery for dogs with significant hip pain/lameness. Others will argue the surgery is justified in non-symptomatic dogs to avoid OA, although this approach makes it likely that some dogs that will never suffer from their hip dysplasia will be operated on (this is also true of JPS, but JPS is a much less invasive procedure with a very low risk of complications).

The potential impact of major orthopaedic surgery at such a young age, with the consequent exercise restriction and impact on behavioural training and socialisation, should also be considered.

TPO and DPO are not commonly performed in specialist practice in the UK because of the limitations previously described. Those of us who reserve surgery for puppies with significant clinical signs find that by the time hip dysplasia has been diagnosed, secondary osseous changes are often already present in the hip.

Furthermore, given that total hip replacement (THR) has become a very predictable and successful surgery, puppies with mildly symptomatic hip dysplasia will often be managed non-surgically in the first instance with a view to THR at a later date, if a persistent clinical issue is present.

We are all familiar with femoral head and neck excision (FHNE). It can be a very useful procedure for patients with severe hip pain – especially smaller patients, and if financial circumstances mean that THR is not an option.

The aim of FHNE is to prevent hip pain by eliminating contact between the acetabulum and the femoral head. Removal of the femoral head and neck results in the formation of a fibrous pseudoarthrosis that, along with the surrounding muscles, supports the hip in the absence of a direct articulation. FHNE can be a very effective surgery, generally more so in the smaller the patient (it is often stated that dogs less than 15kg to 20kg do better than larger dogs).

The concern with FHNE is that the fibrous pseudoarthrosis that forms can restrict hip mobility and result in persistent hip pain. To minimise the impact of this, all patients should have physical therapy/hydrotherapy after FHNE; this is particularly important for larger patients, for which a proactive rehabilitation programme is critical for a good outcome. Return to maximal function after FHNE can take as long as six months.

The outcome following FHNE is unpredictable. Progressive muscle atrophy, restrictive hip mobility and proximal migration of the femur can be seen after surgery. Most owners are satisfied with the outcome after FHNE, but may not recognise that their pet has an altered gait. One study looked at the outcome of FHNE in cats and dogs (with the majority being less than 15kg) using a client questionnaire, as well as objective data (kinetic and kinematic gait analysis), and reported good functional results in 38% of patients, satisfactory results in 20% and unsatisfactory results in 42%1.

Most vets with some surgical experience will be able to perform FHNE and it is, therefore, very applicable to general practice; however, some important points must be considered.

Firstly, do make sure that your diagnosis is correct. It is not uncommon for dogs referred with a hip dysplasia diagnosis to be lame for another reason. Cruciate disease – especially very early cruciate disease – will often cause a chronic low-grade lameness that is misinterpreted as hip dysplasia.

Similarly, patients with hip dysplasia/OA that acutely deteriorate should always be carefully evaluated for other orthopaedic/spinal conditions or septic arthritis in the affected hip.

Secondly, patients with very mild/intermittent clinical signs – especially those that respond well to medication – are not likely to be good candidates for FHNE, given that patients can have persistent hip pain/lameness after FHNE.

Finally, pay close attention to surgical technique. Tenotomy of the deep gluteal muscle, which is sometimes part of an approach to the hip, must be avoided so as to not further destabilise the hip. The position of the osteotomy is important to avoid bone spurs that may impinge on the acetabulum after surgery. The osteotomy is ideally performed with an oscillating saw. With care, an osteotome and mallet can be used, but these risk fracture of the femur if the bone is brittle or if the cut is directed in the wrong direction. A chisel (which has a bevel on only one edge) should never be used; this is much more likely to result in femoral fracture.

THR has been performed in dogs for more than 40 years. THR systems continue to evolve and improve and, in the right hands, THR is a very predictable technique with good outcomes.

The first THR systems in dogs (and people) were cemented systems. Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) cement is used to provide immediate stabilisation of the femoral stem and acetabular cup. Cemented systems are still used and can work well, but concerns relating to cement longevity have led to cementless systems gaining in popularity over the past 20 years.

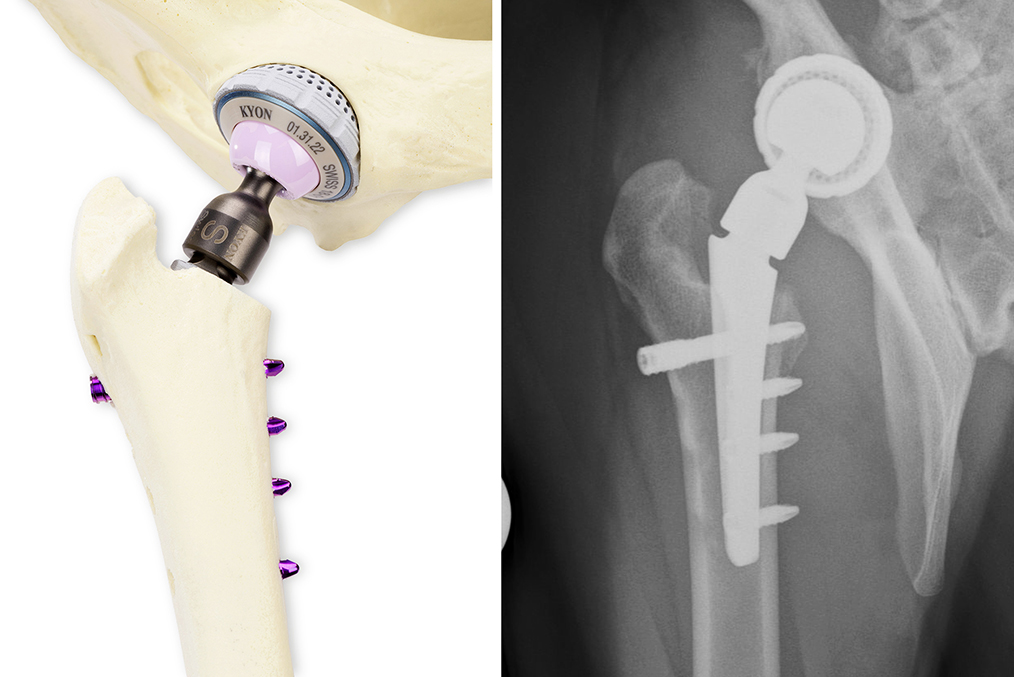

Two of the most commonly used cementless systems are the Biomedtrix BFX system and the Kyon Zurich hip. Both use a press-fit cup. The BFX femoral stem also relies on a press-fit, often with an additional lateral bolt to reduce the risk of stem subsidence. The Zurich stem relies on screw fixation for immediate stability.

Both systems’ implants are designed to encourage bone in-growth/on-growth to provide long-term stability.

The biggest change in THR use over the past 15 years has been the development of a cemented THR system for smaller patients, allowing even very small dogs, as well as cats, to benefit from THR. These smaller patients do very well after THR, and it should be considered as an alternative option in any patient requiring FHNE.

Often, these smaller patients will have conditions other than hip dysplasia. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis is the most common indication in cats, and Legg-Calve-Perthes disease is a common indication in small dogs. As a further exciting development for the smaller patients, mini cementless THR systems are now also available. Compared to FHNE, THR is more likely to return a patient to full function without pain. However, it is not the right choice for every patient or owner.

Of course, a big financial difference exists, as well as a big difference in aftercare. Strict exercise restriction is required after THR, generally for at least eight weeks, whereas FHNE patients are encouraged to be active soon after surgery. For some owners, this will sway their treatment choice.

Both FHNE and THR can result in complications. After FHNE, the primary concern is poor limb function. After THR, the complications are more likely to require further surgery and, therefore, possibly additional cost to the owner. Most studies indicate a 10% to 15% complication rate after THR. Early complications after surgery include luxation, femoral fracture and implant loosening.

It is important THR surgery is performed in the right environment and with appropriate precautions to avoid infection, which will often require implant removal to resolve. As with any highly technical procedure, complication rates tend to reduce with surgeon experience.

So, now we know the surgical options, when should we consider consulting a surgeon? It might be worth discussing hip dysplasia with owners of at-risk breeds (such as the Labrador retriever, German shepherd dog and so forth) at their puppy vaccinations and if owners might be interested in JPS, then consider checking the hips for an Ortolani sign (this is likely to require sedation), or contact a surgeon offering the technique to discuss.

Young dogs with lameness localised to the hips should have hip radiographs taken, but importantly, they should also be assessed for an Ortolani sign since radiographs can provide a false-negative result for hip dysplasia in young patients.

If hip dysplasia is confirmed, and no secondary osseous changes, then DPO may be an option, but many owners and surgeons – especially if the clinical signs are mild – are likely to advocate non-surgical management in the first instance. Consulting with a surgeon early can nonetheless be helpful in this scenario.

Young dogs with relatively severe lameness that are not candidates for DPO may be considered for early THR. The author generally prefers to delay THR until at least 10 months of age, but in some circumstances, will perform THR in younger dogs. Dogs with severe hip dysplasia and luxated (luxoid) hips can have severely compromised mobility, and are often treated with early THR.

Dogs older than 10 months of age with clinical signs attributable to hip dysplasia are managed non-surgically in the first instance. This will include exercise modification, NSAIDs and physical therapy (physiotherapy/hydrotherapy).

Owners will have different preferences for how long they pursue these strategies before seeking further advice or considering other options, but THR becomes an option for any patient with clinical signs despite these strategies, for dogs requiring long-term medication or long-term exercise restriction to manage their hip dysplasia/OA, or for dogs having frequent flare-ups of hip pain due to hip OA.

Weight management is an important part of the non-surgical management of OA, but patients that are possible THR candidates should not have surgery delayed while weight loss is attempted. Such patients will generally be inactive due to their hip disease, and experience suggests significant weight loss can be a very slow process.

It is generally better to improve patient comfort and activity through THR, and the weight loss will then be far easier to achieve.

Because the outcome after FHNE is less predictable than after THR, where THR is not an option for whatever reason, the author is more likely to recommend pursuing non-surgical o ptions for longer, reserving FHNE for cases where the hip dysplasia/OA is having more of an impact on the patient.

These patients will benefit from physiotherapy and hydrotherapy to improve muscle mass, which may help to avoid surgery, but will also help improve the postoperative recovery if FHNE does prove necessary.

The author is often asked if an upper age limit exists to THR, and the short answer is no. As long as the patient is in relatively good health, then THR remains an option.

However, older patients may be at increased risk of complications because remodelling of the hip is likely to be more extreme and also because changes to bone density may be present, and healing times as patients get older.