19 Nov 2019

David Walker and Shaun Calleja review medical conditions affecting the stomach, including an update on management and treatment.

Image: otsphoto / Adobe Stock

Gastropathies are commonly encountered, both in first opinion and referral practice. They are a significant source of worry for owners and vets alike, particularly when signs are persistent. Unfortunately, evidence for treatment is often anecdotal and conflicting, hampering consistent management of gastric diseases. This increases the likelihood of owner and vet frustration.

Gastric diseases can range from minor complaints requiring little intervention and with good prognosis, to severe disease leading to, or exacerbating, significant morbidity and mortality risks. Good working knowledge of the latest ideas for management of gastropathies is important and can significantly improve patient outcome. This is particularly true for chronic diseases and conditions affecting critically ill patients. Recent advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology of disease is opening promising new avenues for treatment, although some of these ideas are yet to show clinical benefit.

This article will discuss the treatment of gastric disease, from mild acute disease to more life-threatening presentations. Diffuse or multifocal enteropathies are often present in conjunction with gastric disease; therefore, this article will include some discussion of enteropathy. Controversies and misconceptions surrounding certain conditions are also discussed.

A first-of-its-kind nutrition that focuses on microbiome health: NEW Hill’s Prescription Diet Gastrointestinal Biome with ActivBiome+ Technology revolutionises the way you address fibre-responsive GI issues.

Gastric diseases are a common cause of illness in small animals, with gastrointestinal (GI) signs making up just less than 25% of problems identified in primary care practice1. Effective treatment of gastric disease is, therefore, essential to achieve a satisfactory outcome for patients and owners alike.

This article will review medical conditions affecting the stomach – as diffuse gastroenteropathy is frequently identified as a single disease entity, brief discussion of enteropathy is also required.

As with all presentations, thorough history taking and physical examination are important to help refine problems and target our approach. Signalment (for example, breed and sex predispositions), duration of clinical signs, and clues to possible causes of GI upset (for example, dietary indiscretion, toxin exposure, signs of extra-GI disease) can all help formulate appropriate plans for further investigation and/or management.

Physical examination, including rectal exam, is essential and sometimes helps determine the initial treatment administered – surgical emergencies (for example, gastric dilatation and volvulus; Figure 1, foreign body ingestion, intussusception), anaemia, haemorrhage (for example, melaena; Figure 2), hypovolaemia, dehydration, uraemia, caustic toxin ingestion and neoplasia can all sometimes be suspected based on clinical examination. Concurrent problems that may alter the owners’ approach are also important and should not be overlooked.

In the otherwise healthy patient presenting with acute-onset gastric signs (for example, vomiting, inappetence), where surgical or extra-GI conditions have been excluded, a presumptive diagnosis of acute gastritis can be made. These patients can be treated supportively with oral fluid therapy and withholding food for 24 hours, then feeding a highly digestible diet. Further investigation may be recommended in cases requiring IV fluids2.

Protectants/absorbents can also be used – examples include bismuth subsalicylate (1ml/5kg by mouth every eight hours)2. Anti-emetics, such as maropitant, are also useful; however, it is important to try to exclude obstructive diseases beforehand. No evidence supporting acid suppression in such cases exists3.

Gastric parasites are not commonly present in untravelled UK pets, but endoparasticides can be used in cases of unexplained gastritis.

Where vomiting and diarrhoea occur concurrently, use of an anti-diarrhoeal probiotic paste can help accelerate the resolution of signs and reduce the need for additional intervention4.

Acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea syndrome (AHDS), previously called haemorrhagic gastroenteritis, necessitates significantly more intensive treatment than aforementioned. However, evidence has suggested AHDS does not involve the stomach5. Although the same study suggested AHDS was associated with clostridial overgrowth and mucosal necrosis was seen on histology, the role of antibiotics in this disease remains controversial.

Use of amoxicillin/clavulanate did not improve outcomes in aseptic cases of AHDS6. Separately, no difference was found in the incidence of bacteraemia in dogs with AHDS, compared to healthy control dogs; no association existed between bacteraemia and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) or outcome in affected patients7. This suggests antibiotics are not indicated in cases of AHDS; however, the sensitivity of blood culture can be low8. Anecdotally, many clinicians would consider antimicrobial therapy appropriate in cases with significant risk factors for, or showing signs of, sepsis/SIRS.

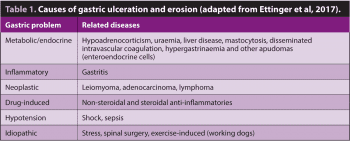

Gastric ulceration and erosion (GUE) is a broad disease category, arising from a number of primary gastric and extra-GI conditions (Table 1). Presenting cases also show significant variation in the duration and severity of clinical signs, necessitating a patient-specific approach.

Initial emergency stabilisation is often required in these cases – including correction of hypovolaemia, anaemia and electrolyte/acid-base abnormalities – along with analgesia. Investigations should also be aimed at identifying the underlying cause of GUE, which may help further direct treatment.

Acid suppression is considered the cornerstone of treatment of GUE, with the rate of ulcer healing increasing as the degree and duration of acid suppression is increased9. Proton pump inhibitors (PPI; for example, omeprazole) given twice daily are considered superior to other gastroprotectants for treating GUE and should be given to all patients with presumed GUE3. As the intracellular proton concentration in parietal cells is highest after a prolonged fast, omeprazole should be administered 30 to 60 minutes before feeding, including the first feed of the day10.

No evidence exists supporting the concurrent use of PPIs and other gastroprotectants (for example, histamine receptor antagonists, sucralfate), with the effect of one drug likely affecting the mechanism of action of another, resulting in reduced treatment efficacy overall. Omeprazole has also been shown to be highly efficacious for the treatment and prevention of exercise-induced gastric ulceration11,12.

Dogs and cats receiving prolonged PPI therapy (more than three to four weeks) should be weaned gradually3.

Acid suppression using histamine antagonists is also appropriate in dogs with mast cell disease – not only in cases showing intestinal signs or at risk of degranulation, but in all cases with measurable tumours13. Because of the increased efficacy of PPIs, compared to histamine antagonists, omeprazole should be preferentially used in cases of GUE secondary to mast cell tumours2,3.

Acid suppression can increase gastric bacterial load, which can increase the risk of severe aspiration pneumonia in vomiting patients.

The benefits of prophylactic acid suppression with chronic kidney disease are also unclear – GUE secondary to uraemic gastropathy is uncommon in dogs and cats14,15; affected patients and owners are also likely to benefit from reductions in the number of administered medications.

Other treatments used in cases of GUE include misoprostol – a prostaglandin E2 analogue that is effective at treating GUE secondary to NSAID (not glucocorticoid) use3. Misoprostol has also been used prophylactically in dogs receiving chronic NSAID therapy; for example, for OA or at risk of ulceration3.

Large, non-resolving or perforated ulcers require surgical resection (Figure 3). Pyloric perforation has been associated with NSAID therapy, with a reported mortality rate of 64%16.

Chronic inflammatory gastritis is common, with histological changes identified in 35% of dogs undergoing investigations for chronic vomiting and 26% to 48% of asymptomatic dogs17,18.

The role of bacterial infection, specifically Helicobacter species, in triggering chronic gastritis remains controversial, despite numerous studies.

Although some studies showed associations between NHPH infection and gastritis, a clear causative relationship was not established in all studies21,23-25.

Clinical and histological improvement have been reported in cases treated for NHPH when concurrent infection and gastritis were identified histologically2,22. However, recrudescence after cessation of treatment is very common, with PCR analysis suggesting transient suppression, rather than eradication2,22.

Although an optimal treatment protocol for NHPH infection is not available, a combination of metronidazole (10mg/kg every 12 hours), clarithromycin (7.5mg/kg every 12 hours) and amoxicillin (20mg/kg every 12 hours) used for 14 to 17 days appears to be most effective2. No evidence that acid suppression is beneficial in the eradication of NHPH in dogs and cats exists3. The need for treatment should be based on clinical signs and histological findings – as aforementioned, many cases of gastritis also have intestinal inflammation unexplained by gastric NHPH infection alone.

The development of antimicrobial resistance and the effect of antibiotic therapy on the host microbiome are also of increasing concern26-28.

Treatment of chronic gastroenteropathies in dogs and cats is often empirical, using a step-wise approach and classified according to response to treatment – food-responsive, steroid-responsive and antibiotic-responsive. Unfortunately, evidence for treatment efficacy is limited.

Strong evidence exists to support the use of elimination diets in dogs and cats with chronic enteropathies – long-term clinical remission can be achieved with diet alone29. The most effective diet has not been established; however, high-carbohydrate, low-fat diets have been recommended – this is suggested to facilitate gastric emptying. Hydrolysed protein diets are often used as these may be less immunogenic and various hydrolysed diets are available in the UK. These diets may also contain immunomodulating substances that help reduce intestinal inflammation2.

The chosen test diet is fed exclusively for two to three weeks and patients monitored closely. If clinical signs improve, a challenge with the original diet is often recommended, with relapse confirming a diagnosis of food-responsive enteropathy – this suggestion is not always accepted by owners. Once signs have resolved, provocation with individual ingredients (for example, beef and chicken) can be performed to establish a list of “safe” foods. If there is no response to diet, a different elimination diet can be used for a further two weeks.

If dietary therapy fails, immunosuppressive therapy can be started. The choice of immunosuppressive protocol likely depends on the severity of clinical signs and histological changes. Evidence exists to support single-agent prednisolone therapy in patients with chronic enteropathy29.

Additional immunosuppression may be needed in cases with severe clinical signs and pathological changes, or where response to glucocorticoids alone is inadequate. Evidence supports using either chlorambucil or ciclosporin in dogs30,31. One study suggested a prednisolone-chlorambucil combination was more effective, compared to azathioprine; however, this was a small, retrospective study, and clinician preference and experience continues to play a role in drug selection30.

The evidence for second-line drugs is very limited in cats – chlorambucil is effective and well-tolerated, with steroid-refractory chronic enteropathies, as well as small cell lymphoma32. Ciclosporin is also suggested to be effective, although evidence is more anecdotal; cats should be tested for Toxoplasma exposure using serology prior to starting treatment, as reactivation can occur32.

Once patients are in remission, gradual tapering of prednisolone can be attempted, with the aim of discontinuing medication or reaching the lowest tolerated dose.

Antibiotic-responsive enteropathy (ARE) remains a controversial entity. As many of these cases present with small intestinal/mixed bowel diarrhoea, rather than signs of gastritis, ARE will not be further discussed here.

Further investigation into the pathogenesis of chronic enteropathies has suggested a complex interplay between host genetics, intestinal epithelium and immune system, the intestinal microbiome and dietary constituents. The exact role of these components in the development of disease is yet to be elucidated, but studies have suggested a major role for the intestinal microbiome27, 28. This has provided new targets for treatment aimed at modifying these interactions and the intestinal environment.

Increasing evidence supports the use of probiotics for intestinal disease in people2; however, evidence in dogs is limited29. Probiotic supplements have shown some benefit in the treatment of chronic enteropathies in dogs2,29. Faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has also been used in the treatment of intestinal disease, with some promising results; suggested guidelines for its use have also been published33,34. However, data is very limited, and the long-term efficacy and safety of FMT is unknown; the survival of organisms through the stomach following oral FMT is also of concern34,35.

Other, less common, forms of gastritis include atrophic gastritis and hypertrophic gastritis. The former has been reported in the Norwegian lundehund, associated with gastric adenocarcinoma2. Reports of treatment of atrophic gastritis are limited; however, dietary modification, Helicobacter species eradication and immunosuppression have been effective in human cases, and in limited canine case reports24,36.

Hypertrophic gastritis is often breed-related (basenji, Drentse patrijshond and shih-tzu)2. Anecdotal reports have suggested a response to antibiotics in affected basenjis.

No figures for prognosis and survival in dogs and cats with gastritis are reported. However, cases with idiopathic gastritis that show good response to therapy would be expected to have a good prognosis. Conversely, cases of gastritis that prove refractory to treatment or where neoplasia develops as a consequence of gastritis (for example, Norwegian lundehund) are likely to have a poorer prognosis.

Delayed gastric emptying and motility disorders are a common consequence of many conditions, both primary gastric and extra-GI – these are broadly summarised in Panel 1.

Mechanical obstruction:

Congenital stenosis

Foreign bodies

Mucosal/muscular hypertrophy

Granulomas

Polyps

Neoplasia

Extra-gastric masses

Functional obstruction:

Gastritis

Gastric disorders

Ulcers

Neoplasia

Gastroenteritis

Peritonitis/pancreatitis

Metabolic (for example, hypoadrenocorticism)

Surgery

Drugs ( for example, anticholinergics and opioids)

Idiopathic, dysautonomia

Nervous inhibition (trauma, pain, anxiety)

GI dysmotility (both hypomotility and, less often, hyper-motility) is also seen commonly in critically ill patients (50% to 60% of critically ill human patients); risk factors in people include mechanical ventilation, sepsis/SIRS, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, shock and trauma39.

GI dysmotility then causes complications in its own right, including aspiration pneumonia, oesophagitis, and bacterial translocation and sepsis39. Signalment, history and physical examination are important for prioritising differential diagnoses, and guide further investigation/treatment in these cases.

In non-obstructive gastric motility disorders, dietary modification can be helpful, particularly when patients are otherwise clinically well. Semiliquid, low-fat, low-protein diets with increased feeding frequency may help increase gastric emptying. If this is not effective, medical management can be considered.

No controlled clinical trials have been performed in dogs and cats; however, cisapride and erythromycin (0.5mg/kg to 1mg/kg by mouth every eight hours – antimicrobial doses can cause GI upset) are likely to be the most efficacious drugs and can be given orally2,39. Medication can be trialled for 5 to 10 days to assess response.

Metoclopramide is often used as a first-line prokinetic agent in critically ill or hospitalised patients. It can be administered as a constant rate infusion and has the added benefit of a centrally mediated antiemetic effect40.

Ranitidine may also have a prokinetic effect and can be used as an adjunctive treatment; however, one study has shown no significant effect of ranitidine on GI transit times41.

Metoclopramide is likely to be less effective than cisapride at promoting the organised gastroduodenal motility required to promote emptying of solids from the stomach. However, cisapride has no antiemetic effects, is only available in oral form and known to have significant drug interactions40.

Erythromycin is a highly effective prokinetic and helps promote the emptying of solids2,39. Although not available in injectable form, a liquid version is available that can be administered via nasal/oesophageal feeding tubes.

Additional treatments that may be of benefit in GI dysmotility secondary to critical illness include early nutritional intervention, judicious fluid therapy to help maintain perfusion while avoiding overhydration and early ambulation39.

Multimodal analgesia to help minimise drug-induced dysmotility (for example, opioids) is also recommended. Addressing the underlying condition and correcting metabolic derangements will also improve GI function.

Bilious vomiting syndrome is a condition of dogs characterised by vomiting early in the morning or after a prolonged starve. Control may be achieved by feeding late at night. Alternatively, medical management as aforementioned may be useful.

Research is constantly expanding our understanding of the aetiology and pathophysiology of disease.

Previously overlooked gastric diseases are also receiving more attention. This will likely provide new therapeutic options and enable more targeted treatment. This should improve outcomes for both patients and owners in the future.