11 Oct 2022

Emma Baker BVetMed, MSc, MRCVS, and Emma Brown, BVSc, PGDip, CCAB, MRCVS in the second of a two-part article, describe long-term treatment options.

Image: © andreaobzerova / Adobe Stock

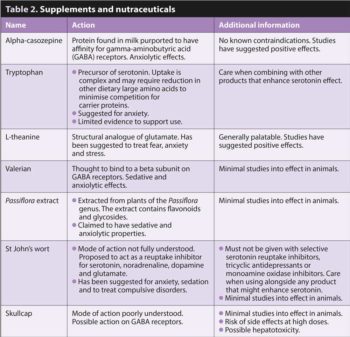

This article is the second in a two-part series on managing and treating sound sensitivities related to fear or anxiety. The previous article (VT50.39) discussed the aetiologies and diagnosis for sound-sensitive animals, and advised on short-term management strategies around predicted noise events. Tables 1 and 2 have been included from the previous article. This follow-up article discusses long-term treatment.

As with a physical health case, working methodically from first principles is the most thorough approach. The principles of a behaviour consultation are outlined and applied to a sound sensitivity case below.

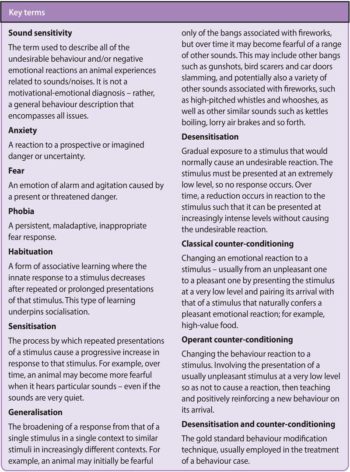

Identify the triggers for the negative emotional state/unwanted behaviour the client is reporting. For many sound-sensitive cases, this is straightforward as the client will also hear the noise just before their pet reacts. As a pet becomes more sensitised to sounds, it may also react to stimuli that predict the arrival of those sounds, such as darkness in the evening before a firework display or changes in electrostatic pressure before a thunderstorm.

Some triggers for unwanted behaviour do not initially seem related to a fear of noise. Cases may present as an owner-absent issue if a dog was frightened by a loud noise while alone. The animal can associate the noise with being isolated and become fearful of being left.

Conversely, if a dog has a pre-existing separation-related problem, and a loud noise occurs while it is already alone and distressed, having no owner as a coping strategy can sensitise the animal to the noise more quickly. Cases also exist that present for reactivity directed at their owners, which, during anamnesis, we learn is triggered when the owners attempt to move it from a hiding place or thwart its noise-fear coping strategy in other ways.

Assess the body language and behaviour performed by the animal during its reaction to the trigger. This can be done by live observation, watching video footage or from history-taking (care must be taken not to deliberately engineer a situation that triggers the dog, though).

Identify which emotional state the behaviour corresponds with and the outcome the animal is intending by choosing that behaviour.

Physical health issues can directly affect a sound-sensitive pet. Pain can confound its coping strategy and result in sensitisation to certain noises. It may struggle to retreat to its den on hearing a loud noise if it is arthritic. It may feel conflicted about seeking reassurance from its owners if this results in being picked up/cuddled, which gives it discomfort.

Health problems also impact indirectly on emotional health. Pain and disease increase an animal’s emotional arousal, and reduce its tolerance of stimuli it previously coped with. Chronic stress can affect learned associations/habituation in a number of ways1. Therefore, an animal that could previously tolerate loud noises when it was healthy and pain-free may no longer be able to.

The clinician should pay particular attention to middle-aged or older patients presenting for sound sensitivity. In cases where sound sensitivity was diagnosed with pain, the animals presented significantly (four years) older than cases without pain, in a retrospective study of University of Lincoln sound sensitive dog cases2.

Protecting the animal from triggers manages its emotional welfare, which we as veterinarians are responsible for.

It lowers its emotional arousal and reduces its physiological stress response – in particular its cortisol level, which above a certain threshold, inhibits new, associative learning within the hippocampus3. This is the type of learning the behaviour modification plan relies on, so must be facilitated3.

With respect to sound sensitivity, protection will include the management and medication advised in the previous article. Protecting a pet from exposure to noises will prevent it becoming sensitised and its fear from generalising to other sounds.

Providing a reliable escape place that minimises the phobic event is very important4. Train a dog to enjoy a safe, soundproof, flash-proof space by tempting it in with a trail of food, and placing chews or toys in there.

Teaching it to go in there on cue when it hears a noise will change its coping strategy from one that is potentially reliant to its owner to a more independent one. This means it can continue performing it even if the owner is absent during a noise event.

Dog-appeasing pheromone (DAP) may also assist with sound-sensitive cases. A blinded, placebo-controlled trial revealed that dogs had significantly reduced fear and anxiety scores when subjected to a thunder simulation if they were fitted with a DAP collar. The study also discovered that dogs in the DAP group made significantly more use of their “hide” (den) later in the study, which the researchers postulated shows an adaptive settling response absent from the placebo group5.

A second study reported that the use of DAP, together with a planned desensitisation and counter-conditioning (DSCC) programme to recorded sounds on CD had a higher owner-reported success rate than either of those techniques alone6.

A third report claimed the use of DAP diffusers resulted in higher owner satisfaction level and reported improvements in dogs’ clinical signs during firework exposure7. A recent review, however, commented that the inclusion of behavioural advice in the treatment plan of this study does not allow us to distinguish between the effects of that and the pheromone treatment8.

With respect to sound sensitivity, desensitisation and counter-conditioning often involves playing specifically designed noise recordings at a very low level, so the animal can hear the noises, but does not react4.

The volume of the noises is gradually turned up as the animal gets used to them, and over time, the animal can cope with an increasing volume. When the animal can tolerate with a loud volume without reacting, it is turned down again and the process is repeated while giving the animal high-value food. This reconditions the animal’s emotional reaction and is more effective than desensitisation alone9.

Using sound recordings in this manner can be time-consuming and compliance can be poor, but Levine et al6 found that if owners complied with the instructions that accompany the sound recording for 60 days, a roughly 60% reduction occurred in the number of unwanted behaviour signs shown in the presence of loud noises.

This study also found the clarity of instructions accompanying the recording is more important than the quality of the sound system delivering it.

Veterinary behaviourists Sarah Heath and Jon Bowen joined forces with Dogs Trust to share a number of sound recordings on its website that may be downloaded for free10. The accompanying instructions are very clear and easy to follow for pet owners.

Although planned, systematic DSCC through sound recordings is considered gold standard; a recent online questionnaire completed by more than 1,200 dog owners reported that “ad hoc DSCC” was found to be more effective8. Planned DSCC to sound recordings had a reported effectiveness of 54.4% while “giving a treat or playing with the dog after a noise has occurred” was considered effective by 70.8% of those who tried it.

This may be more down to compliance than technique, but in the busy modern world where behaviourists are under pressure to produce training plans that fit in with owners’ lifestyles, this finding may be reassuring. DSCC of any type is the only technique described in the questionnaire that reduced fear progression by the next predicted noise event.

The same questionnaire study also reported that “relaxation techniques” had a success rate of 69.3%8, although it did not discriminate between types of relaxation and we do not know if these techniques were coping strategies that helped in the short-term, rather than long-term treatment ideals, as no reduction in fear progression was recorded. Overall3 has a training protocol for relaxation and teaching a “settle” is a long-standing method of asking for calm behaviour.

These regimes are designed around the bio-feedback mechanism that enables deep breaths and lying calmly to lower cardiac arousal, which in turn lowers emotional arousal11 – biological beta-blockers, one might say.

The 2020 review notes that relaxation techniques used to be part of the DSCC process and considers the owner-reported success rate important enough to recommend them alongside DSCC and psychopharmacotherapy8.

With any treatment plan, if an animal is continuing to react severely to unavoidable triggers or its general emotional arousal level is such that it is not progressing with treatment, its emotional health and welfare remains compromised.

In such cases, prescription medication must be considered. By the time owners seek help, the reaction has often generalised to more commonplace noises that are harder to address; for example, the slamming of car doors or the rumble of a passing wheelie bin.

These sounds cannot be predicted or managed in the same fashion that a firework display can. In these cases, the medication required is that which can lower emotional arousal, reduce fear/anxiety and assist with new learning.

With the exception of imepitoin (which can be used for management and treatment), several classes of drugs exist that can assist behaviour cases over the longer term12. The medications listed in Table 3 are bioavailable within hours of ingestion, but their mechanism of action – neurotransmitter re-uptake inhibition – induces downregulation of post-synaptic receptors and to asses the full effects of these changes requires weeks of treatment.

These medications are, therefore, unsuitable for use in managing specific noise events.

Although instructions and recordings are available for owners to treat these cases themselves at home, referral to a behaviourist remains the best option for a number of reasons. An appreciation of other behavioural comorbidities is vital to establish the correct diagnosis to advise the appropriate treatment14.

Protection advice will vary greatly. For instance, some dogs can be taught to habituate to ear defenders when high volumes of noise are unavoidable in their environment. “Mutt muffs” were designed for working dogs in the forces to be able to travel in helicopters, but training for the owner and their pet would be required before use.

Treatment is rarely as simple as DSCC alone. Often, elements of the treatment plan will need to be tailored to each specific case. For instance, if a dog reacts by bolting when hearing noise on a walk, training that noise as a cue to recall will ensure the dog’s safety more quickly.

This article has attempted to highlight how gold-standard treatment for fear/anxiety-based sound cases should be undertaken, so that referring veterinarians can be more informed when they are considering referral and advising their clients.

Long-term treatment, rather than simply managing pets with medication every Bonfire Night, can make a big difference to their quality of life and can prevent the problem worsening over time.

A list of registered behaviourists to refer to is available on the Fellowship of Animal Behaviour Clinicians website15, where readers can also find a blog post on this subject and on many more.

Sadly, although one study reported 49% of people’s dogs displayed some fearful or anxious behaviour around loud noises16, the same study also found that only 15% of owners would bring this up with their vet. Our industry still has a great deal of work to do to safeguard the pets under our care. Educating our profession to encourage discussion about behaviour issues at the vets and continuing to share our behaviour knowledge with clients on the subject will go a long way to tackling this issue.