14 Nov 2023

Norbert Mencke highlights the issues around parasites in cats and how to help owners achieve a better understanding.

Image © TiHo Hannover

Globally, cat numbers are increasing – and at a faster rate than dogs in many countries. Also, as more of us live closely with cats, we must improve our understanding of feline parasites and not extrapolate from our knowledge of canine parasitology.

This key theme was discussed by 35 leading parasitologists, veterinary clinicians and expert epidemiologists during the second Vetoquinol Scientific Roundtable Parasitology event in Athens, Greece.

Across three days, current parasitology research was shared, with emphasis on improving understanding of, and approaches to, cat parasites and their public health impact. Discussion focused on how preventive health and parasitology could be more “cat-centric”.

Roundworms (Toxocara cati, Toxascaris leonina) and hookworms (Ancylostoma tubaeforme, Ancylostoma ceylanicum) spread by cats represent a significant human and animal health risk globally.

Smaragda Sotiraki – senior researcher and European veterinary specialist in parasitology at the Hellenic Agricultural Organisation in Thessaloniki, Greece – explained: “More evidence is coming to light about the abundance of these parasites in everyday environments and their risk to human health. However, it’s not something we are regularly discussing with owners.”

Ana Margarida Alho – veterinarian parasitologist and public health medical resident in ACES Lisboa Norte, Portugal – emphasised the importance of addressing roundworms in cats. She said: “Toxocariasis in humans — infection caused by Toxocara species — is one of the five most neglected diseases according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention1.

“We’ve found that 85.7% of public sandpits and 50% of public parks evaluated in greater Lisbon were contaminated with Toxocara species eggs2. Within the soil samples, more than 85% identified as T cati and not the canine roundworm T canis, indicating cats, more than dogs, carry a greater risk of contributing to toxocariasis in humans2.”

There is also a general lack of awareness of pet owners concerning zoonotic risk behaviours: in Portugal, 43.1% of the owners allowed pets to sleep in their beds3 and 75.5% to lick their faces3, and most of them had never heard of zoonosis4.

Participants agreed that veterinary professionals in clinics could use available data to better educate cat owners about roundworms and emphasise the need for robust deworming protocols.

Aelurostrongylus abstrusus – “the cat lungworm” – remains the primary parasitic respiratory nematode in cats.

The route of infection is predominantly via intermediate hosts such as slugs and snails, and paratenic hosts such as rodents, reptiles and birds5-7.

Manuela Schnyder, group leader of veterinary parasitology at the Institute of Parasitology, Vetsuisse, University of Zurich, Switzerland – said: “We need practitioners to pay more attention to potential lungworm infection in cats. Its prevalence is underestimated and is increasingly being shown to be an important reason for complications – for example, during surgery.

Furthermore, clinical signs are sometimes misdiagnosed, as asthma or other diseases, and diagnostics can be challenging because the excretion of larvae in faeces is intermittent8.”

Donato Traversa, full professor of veterinary parasitology and animal parasitic diseases at the University of Teramo Department of Veterinary Medicine in Italy, agreed and indicated: “We need to start testing for this parasite frequently – especially before anaesthesia.

“Additionally, we should conduct more postmortem examinations to establish underlying causes of anaesthetic death. Other than respiratory diseases, A abstrusus can cause serious issues such as pulmonary hypertension and neurological signs, which can cause death or long-term damage without prompt treatment8,9.”

In the past decade, the role of Troglostrongylus brevior causing bronchopneumonia in domestic kittens and young cats has been extensively acknowledged9.

Unlike A abstrusus, it is postulated that T brevior can be transmitted vertically from queen to kittens, making it very pathogenic. In endemic areas, it is prevalent in wildcats (Felis silvestris) and circulates in populations of domestic cats5.

Prof Traversa agreed we need more understanding of T brevior specifically. He said: “T brevior infection is often severe and life-threatening – especially in kittens and young cats. Infections are capable to lead to death in kittens, even without high parasitic loads. Early treatment prevents death and long-term signs and pulmonary damages5.

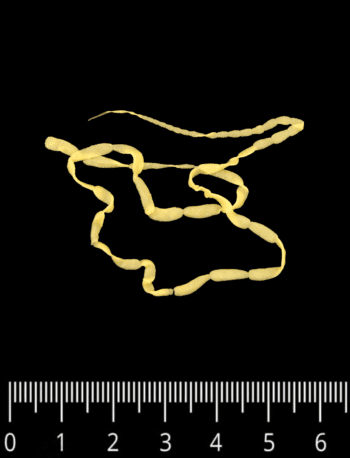

Another frequently underdiagnosed feline parasite group is tapeworm. Discussion centred around the most common species – Dipylidium caninum and Taenia species, and how cat behaviours such as grooming, hunting and face licking can increase risk of infection or transmission to humans.

Cats are avid groomers — more so than most dogs — which is largely how they ingest infected cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis), which are intermediate hosts of the tapeworm (D caninum). And as cats are now part of our families, it’s perhaps worrying that 50% of owners do not realise face licking is a risk factor for parasitic diseases such as tapeworm12.

Paul Overgaauw, professor of animal health and specialist in veterinary microbiology and parasitology at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, said: “Prevalence of D caninum in studies varies from around 4% to 50% of cats13,14.

“But infections are likely under-diagnosed because proglottids are not uniformly shed in faeces, so faecal flotation is not a sensitive enough test.

“When comparing faecal sample flotation with necropsy, the difference in prevalence can be more than 40%12.”

Cats with outside access that hunt wildlife and rodents get easily infected with cestodes via these intermediate hosts. Taenia taeniaeformis is the most prevalent tapeworm – especially in Europe15.

A patent infection with Taenia in cats is likely under-diagnosed due to the infrequent shedding, as only a small percentage of cats shed Taenia species eggs at a given time16.

Poor compliance with preventive measures among cat owners affects tapeworm control disproportionately because many products that prevent fleas don’t offer tapeworm protection, leaving feline and human health at risk.

Prof Overgaauw highlighted a common myth that veterinarians can help address. He said: “Many people think that if they’re treating regularly for fleas then tapeworms can’t be a problem. Prevention from fleas doesn’t address Taenia infections, which can be transmitted via intermediate hosts such as mice, birds and rabbits.”

In addition to transmitting the D caninum tapeworm, C felis can pass on other pathogens such as bacteria, viruses and parasites that may cause diseases in humans.

One example among others is Bartonella henselae – the bacteria known to cause “cat scratch disease” in humans. Dermatological issues associated with fleas also have significant well-being implications for the cat and cost implications for the owner.

Prof Overgaauw said: “Each pet and its premises should be considered an individual flea habitat requiring a treatment protocol tailored to the lifestyle of the animal and its owner. We must overcome the myth that indoor cats are not at risk. Fleas are often the easiest parasite for owners to understand, so there’s an opportunity to improve parasite education, starting with fleas.”

The overriding message from the second Vetoquinol Scientific Roundtable Parasitology event was that more cat-centric parasitological research is required along with proactive, evidence-based approaches in clinics.

Participants agreed veterinarians should consider improving diagnostic measures and offer more regular advice about the “common” parasites to owners, aligning with current research.

Dr Alho summarised the sentiment of all participants to conclude: “There are still huge gaps in our understanding of cat parasites, which makes it challenging to communicate consistent and accurate information to owners. This is worrying as compliance with parasite control is often poor. However, we as veterinarians and parasitologists have the obligation to, and are able to, change this.

“As cats become increasingly important to us, now is the time to re-evaluate how we can best live safely together and enjoy that unique bond.”

Vetoquinol is committed to advancing veterinary parasitology, demonstrated through our groundbreaking launch of Felpreva – the first endectocide spot-on for cats to treat both internal and external parasites, including tapeworms, in addition to providing three months‘ ongoing protection against fleas and ticks.

Vetoquinol works with leading parasitology organisations European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites, the Companion Animal Parasite Council and the World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology, and we support key parasitology conferences across the globe to encourage progress.

The Vetoquinol Scientific Roundtable Parasitology event is just one example of Vetoquinol’s commitment to sharing knowledge and stimulating discussion across the animal health industry to aid innovation.