28 May 2021

Kit Sturgess MA, VetMB, PhD, CertVR, DSAM, CertVC, FRCVS provides an overview of hypothyroidism, diabetes, hypoadrenocorticism and hyperadrenocorticism.

Figure 1. CT of a dog with bilateral adrenomegaly – the right mass is a cortisol-producing adenoma (red arrows) and the left an incidental finding (green circle).

Endocrine diseases are generally slowly progressive, multisystemic problems that, when identified, generally have a good prognosis. Presentation can vary hugely from low-grade, waxing and waning disease to an acute, life-threatening crisis.

Due to their multisystemic impact, endocrine diseases can present with widely varying clinical signs, making it important that the clinician considers the possibility early on in the investigative process (Table 1).

For the acute presentation of collapsed dogs, most likely endocrine causes will be diabetic ketoacidosis or hypoadrenocorticism. This mandates that all severely unwell patients should have blood glucose measured.

On-site measurement of cortisol is helpful, but less critical, as dogs in Addisonian crisis present due to hypovolaemia and electrolyte disturbances that can be managed with IV fluid therapy in the acute phase. However, the possibility of an endocrinopathy should be considered with diagnostic samples obtained before treatment is commenced – particularly if systemic corticosteroids are to be used.

The majority of dogs with endocrine disease, however, present with more chronic, often waxing and waning, histories that allow for a more step-by-step approach to diagnosis. For many clinicians after history and physical examination, the starting point will be routine haematology and biochemistry; these tests can serve to increase or decrease the likelihood of an endocrine disease being present (Table 2).

Diabetes mellitus diagnosis is usually straightforward as dogs do not develop significant hyperglycaemia in response to stress. Values above 9mmol/L would be very rare as a stress response, which, as it is below the renal threshold, will not cause polyuria/polydipsia or glycosuria.

Diabetes can be confidently diagnosed on the basis of the presence of hyperglycaemia in the face of glycosuria. Glycosuria can exist without hyperglycaemia in dogs with renal tubular disease, so it is important that it is not used as the sole diagnostic test.

Classically, Addisonian dogs have cortisol levels below 28nmol/L and do not respond to tetracosactide with post‑adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation levels also below 28nmol/L. Ideally aldosterone should also be measured to show that mineralocorticoid deficiency exists, too, although if sodium is significantly low this is not critical.

For cases where sodium is within the reference interval, but potassium is high and Na:K ratio low, then the measurement of aldosterone is strongly encouraged as hyperkalaemia alone is a common artefact of sampling.

Rare cases are reported of hypoadrenocorticoid dogs with basal cortisol between 28nmol/L and 55nmol/L, and aldosterone-deficient cases with cortisol levels within the expected reference intervals.

Urine cortisol:creatinine ratio is a good negative rule out in systemically well patients where HAC is thought to be unlikely. It is less good in patients that are systemically unwell as disease stress may have elevated circulating cortisol so that the ratio is above the cut-off point.

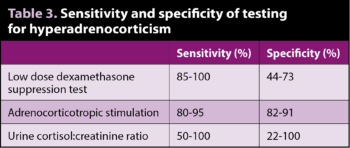

Standard tests are ACTH stimulation and low dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDST); sensitivity and specificity have varied between studies (Table 3). The main advantage of ACTH stimulation testing is the requirement for only two samples, with results being less impacted by patient stress while being hospitalised.

Many endocrinologists prefer LDDST, feeling it is more accurate, but for patients that are very stressed in hospital this may not be the case.

Accuracy is also affected by whether the patient has pituitary or adrenal-dependent HAC.

Ultrasound is a useful adjunctive test, but in sick individuals mild bilateral adrenomegaly may be a stress response and in many patients – especially larger, deep-chested dogs – finding the right adrenal can be challenging. It is also important to remember that not all adrenal masses are cortisol producing and bilateral adrenomegaly can occur for different reasons (Figure 1).

Advanced imaging (of adrenal and pituitary glands) can improve clarity of diagnosis, but is expensive, of limited availability and requires general anaesthesia. Advanced imaging is a valuable tool for surgical planning if adrenalectomy is being contemplated.

Endogenous ACTH and high‑dose DST are indicated in certain specific circumstances.

When faced with a challenging case to diagnose, where clinical signs are mild, it is worth reflecting on what a diagnosis would achieve now (as opposed to later when changes may be more advanced and easier to substantiate) as treatment with trilostane is aimed at managing clinical signs rather than disease cure.

Misdiagnosing HAC and starting trilostane treatment can have significant negative consequences for the patient that may require the high circulating cortisol to cope with the disease stress of another condition. Blocking the patient’s ability to produce cortisol can lead to rapid deterioration.

Regarding hypothyroidism, the classical pattern is of thyroxine (T4) below the reference interval in the face of thyroid‑stimulating hormone (TSH) substantially above the cut-off point of 0.6ng/ml.

A diagnosis of hypothyroidism should not be made on the basis of low total or free T4 measurement alone. A variety of other tests are also used to try to better understand the thyroid axis – including thyrotropin-releasing hormone stimulation testing, antithyroglobulin antibodies, triiodothyronine (T3) and reverse T3 and antithyroid antibody levels. While they add additional information they do not necessarily make the diagnosis clearer.

As with HAC, hypothyroidism is a slowly progressive disease and very rarely results in an endocrine crisis, so for many cases waiting and retesting three to six months later is the appropriate option.

Most dogs have type‑one diabetes caused by an absolute lack of pancreatic insulin production through loss of their beta cells; insulin therapy is therefore required. Most commonly, a biphasic insulin is used and the author usually starts at 0.25IU/kg every 12 hours by SC injection.

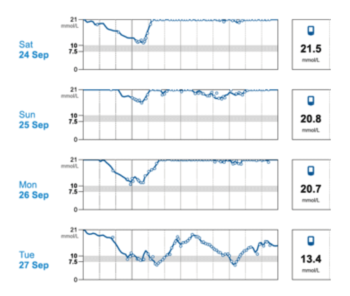

The wider availability of continuous glucose monitors has been a major step forwards in management of diabetes mellitus in dogs (Figure 2).

With hypoadrenocorticism, a combination of mineralocorticoid (usually as desoxycorticosterone pivalate [DOCP; Zycortal]) with a glucocorticoid (most commonly prednisolone) will typically result in good stabilisation of around 80% of cases and adequate stabilisation of a further 15% of cases.

It is important to remember that DOCP (unlike fludrocortisone) has no glucocorticoid activity, so glucocorticoids need to be given at least once daily at low dose (alternate day dosing of glucocorticoids is not recommended) usually around 0.1mg/kg/day to 0.2mg/kg/day of prednisolone.

As glucocorticoids are stress hormones this dose may need to be increased during periods of emotional or disease stress, potentially up to 1mg/kg/day. Intermittent monitoring of electrolytes is required.

Therapy for pituitary‑dependent HAC is most commonly trilostane given once or twice daily. For dogs with mild to moderate signs, the author typically starts at a low dose of around 1mg/kg by mouth every 24 hours and titrates upwards rather than a higher dose of 2mg/kg to 3mg/kg that frequently needs titrating downwards over time. Some patients are more stable when receiving twice-daily dosing.

Monitoring response to treatment is required, but optimal monitoring is controversial as correlation between cortisol results and patient well-being can be poor.

Classically, ACTH stimulation testing is performed four to six hours after dosing, and gives information on basal cortisol levels at peak action and an indication of adrenal reserve. Alternatively, measuring basal cortisol pre-pill (to assess duration of suppression) and four to six hours post-pill can be performed.

Frequency of monitoring should be determined by stability and patient wellness.

Adrenal-dependent HAC offers the option of a surgical or medical approach; pros and cons of each option need to be discussed with the client, and a final decision will be dependent of a large number of factors including size and invasion of the mass, and overall clinical picture of the patient including intercurrent disease and comorbidity, costs, facilities and expertise.

Regarding hypothyroidism, replacement therapy with levothyroxine is the treatment of choice, available both as tablet and liquid preparations. Starting dose is usually around 20µg/kg/day, with some dogs being more stable if the dose is divided and given 12-hourly.

Periodic monitoring of thyroid parameters is recommended; rather than aiming for a specific T4 level, the author prefers to also measure canine TSH aiming for a level lower than 0.03nmol/L, which would indicate that no pituitary drive to increase T4 levels exists, suggesting that thyroid hormone levels are adequate for demand.

Response to treatment can be slow, but if significant response is not seen after six to eight weeks at appropriate doses of levothyroxine then re-evaluation of the original diagnostic test results is worthwhile.

As an overview this article has not focused on specific detailed discussion of each endocrinopathy, but has tried to give pointers of when to suspect endocrine disease, and provide a broad overview of testing and treatment. A variety of good texts, online courses and webinars cover the specifics in more depth and detail.

As most of the endocrine diseases discussed are eminently treatable and may have no impact on longevity (hypoadrenocorticism and hypothyroidism) or good life expectancy even without cure, it is appropriate to consider them undertaking appropriate investigation early on in the diagnostic pathway.

In the vast majority of cases, a diagnosis is for the rest of a patient’s life, so it is worth understanding each patient’s disease as much as possible at the beginning as retrospective testing is always harder to interpret.