24 Oct 2023

Mike Guilliard provides an overview of these skin lesions and explains findings of the surgical techniques used to treat them.

Figure 2. A micro-CT of the digit with a large corn pressing on the deep digital flexor tendon.

The digital flexor tenotomy and tendonectomy procedures for the treatment of digital pad corns in sighthounds was first pioneered about five years ago and initial results were published in Vet Times (VT51.19) and again as a peer-reviewed paper (Guilliard and Doughty, 2021).

They are now widely adopted as the treatments of choice and have been described as a paradigm shift in the understanding and treatment of corns (flyer for the British Veterinary Orthopaedic Association spring meeting 2023).

A corn is a focal area of pad hyperkeratosis (Figure 1) and can protrude both externally and internally (Figure 2) where it gives the appearance of a hollow root.

It is a common cause of severe lameness in sighthound breeds, with a reported prevalence of 5.9% (Lord et al, 2007) and 2.4% (O’Neill et al, 2019) in health surveys of pet greyhounds – figures that are almost certainly artificially low as a result of misdiagnoses.

Presentational history includes a progressive lameness worse on hard ground that is poorly responsive to pain relief. Owners can report depression, with the dog reluctant to exercise, but after successful treatment a vastly improved demeanour occurs. In the consulting room the dog may stand with the foot off the floor, which is indicative of foot pain (Figure 3).

Diagnosis involves the following:

Observation of the pads. The appearance of corns can vary from subtle changes, such as a dark central spot, to marked growths of keratin (Figure 1). An enlarged photograph of the pad aids observation.

Orthogonal palpation with the pad between index finger and thumb may elicit a pain response. Mediolateral palpation is a sensitive test to detect focal thickening.

Differential diagnosis can be a foreign body in the pad or puncture wounds. These can be painful with soft tissue swelling and a sinus tract or ulcer. A mediolateral radiograph of the isolated pad will detect radiopaque objects – typically glass or grit.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that a corn often occurs after successful removal and the author routinely includes foreign body removal together with a superficial digital flexor (SDF) tendonectomy.

The following demographics are taken from two studies of 30 dogs with 40 corns and 100 dogs with 161 corns (Guilliard et al, 2010; Guilliard and Doughty, 2021):

Breeds: greyhound (pet and racing), whippet, lurcher (sighthound crosses).

Corn distribution: approximately 90% occur in the thoracic limbs and approximately 90% occur in digits three and four (central digits).

Age: range from 1 year old to 13 years old.

Multiple corns: 38% of dogs had multiple corns at either initial presentation or from subsequent development.

Historic treatments include the following:

Topical ointments: many have been used to soften or destroy the corn.

Hulling: this vague term involves attempting to remove the corn by paring it down in size or attempting to dig it out with dental curettes.

Surgical excision: the corn can be surgically excised, and the pad sutured.

None of these treatments are likely to provide a permanent resolution, even if the corn has been removed successfully, as 50% recur within a year after excision (Guilliard et al, 2010), hence the cause has not been addressed.

Regarding aetiology, historically the theories are viral (papilloma virus), foreign body penetration and repeated mechanical trauma. Papilloma virus has only been detected in two dogs despite extensive PCR searches.

From histology on greater than 1,000 corns, no foreign bodies were detected, although 4.5% had a secondary penetration of plant material through the soft core. In humans, corns can be from external pressure (tight-fitting footwear) or from anatomic deformity (hammer toe). Evidence for the mechanical aetiological cause is:

Keratin is the structural protein of skin and hyperkeratosis is a natural protective response to repeated mechanical trauma to the integument. Loading of the pad is increased from internal causes, such as fibrosis as in pad penetrations and P3 fractures, and from external causes, such as altered anatomy seen with fracture malunion and PIPJ hyperflexion.

The cause of most corns is not apparent, but genetic factors are undoubtedly involved. Sighthounds have thinner skin than most breeds, with less cushioning of the pads. Conformation is a predisposing factor as seen in bilaterally symmetrical corns.

As hyperkeratosis increases pad loading, it therefore incites the formation of further deposition of keratin. The hypothesis is that by decreasing the pressure and load on the pad, the mechanical trauma will decrease, allowing the corn to exfoliate, resulting in a normal pad. Cutting the digital flexor tendons has this effect, and from the original surgery of a tenotomy of both the SDFT and the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) at the level of the first phalanx (P1) under the foot, the surgeries have evolved from SDF tenotomies at the level of the metacarpus/metatarsus to SDF tendonectomies as the initial procedure.

The following results are taken from the first 100 cases with 161 corns (Guilliard and Doughty, 2021).

The initial procedure of SDF and DDF tenotomies at the level of P1 found that the tenotomised digit needed the support of the adjacent digits to prevent the serious complication of hyperextension of the PIPJ. This led in dogs with two corns on one foot to have a combined SDF and DDF (full) tenotomy on one corn and SDF tenotomy at the metacarpus/tarsus on the second corn. Further evolution led to SDF tenotomy on all corns. The corn was not pared or removed.

Reviewed by telephone consultation at seven days post-surgery, 98% of the full tenotomy cases and 94% of the SDFT cases showed moderate or marked improvement. An eight-week post-surgery follow-up found that 100% of full tenotomy and 91% of SDF tenotomy cases showed slight or no lameness.

The medium-term outcome after one year for the full tenotomy dogs (n = 30) showed 96% had slight or no lameness, and for the SDFT dogs (n = 24) at six to nine months, 83% had slight or no lameness. The corn had exfoliated at eight weeks in 95% of cases. Racing greyhounds returned to the track after six weeks with no loss of form.

Minor complications in both groups were rare (haemorrhage and wound breakdown).

The major complication of the full tenotomy was hyperextension of the PIPJ in either digit three or four, causing a painful keratoma on the palmar skin under the joint (Figure 4).

The other major complication in both groups was reformation of the corn from the tendon(s), with reconnecting occurring from three months to three years after successful initial surgery. This led to the current protocol of an initial SDF tendonectomy in all cases.

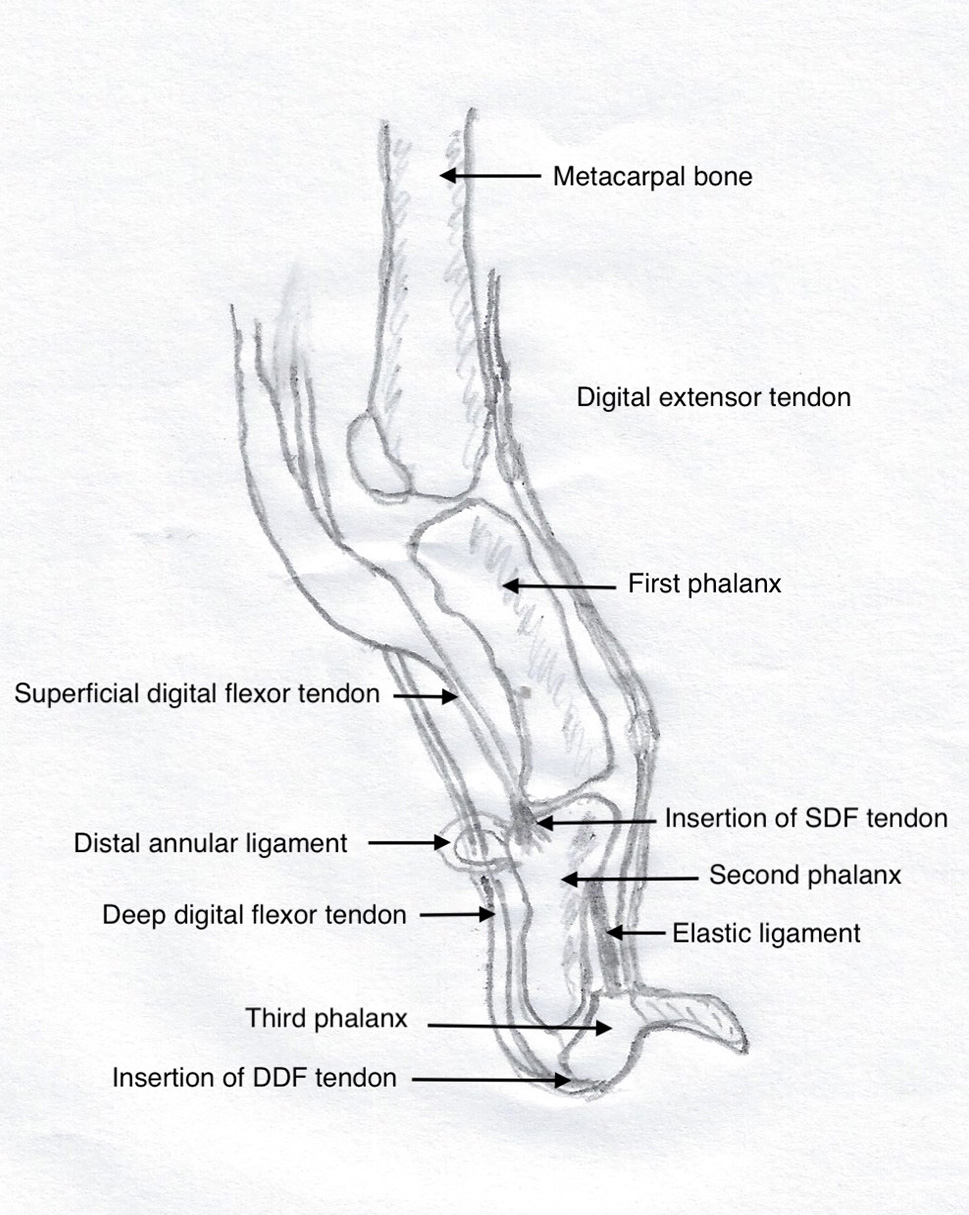

The digital flexor tendons track down the palmar/plantar aspects of the metacarpus/tarsus, constrained by the annular ligaments, to insert of the phalanges. The SDFT inserts on the proximal part of the second phalanx and its function is to flex the PIPJ.

The DDFT inserts on the flexor process of P3 and its function is to flex the distal interphalangeal joint. This is counterbalanced by the dorsal elastic ligament and the digital extensor tendon inserting on the dorsal aspect of P3 (Figure 5).

Severance of the SDFT causes increased extension of the PIPJ and a cranial shift in the nail that remains in contact with the ground. Complete collapse of the PIPJ is prevented by the tension of the DDFT tracking through the annular ligaments (Figure 6).

Severance of the DDFT causes dorsal rotation of P3 from the action of the dorsal elastic ligament, with the nail losing ground contact. Severance of both tendons flattens the digit, although a small degree of flexion remains from the ligamentous support of the PIPJ. The nail is also elevated from the ground (Figure 7).

When performing an SDF tendonectomy, with the dog placed in lateral recumbency and the affected digit positioned uppermost, an assistant places the corn digit in forced extension. The flexor tendons are clearly visible and palpable.

A small skin incision is made along the tendon at the level of the junction of the distal third of the metacarpus/tarsus to expose the white, strap-like SDFT. The fine tendon sheath is incised and peeled off the underlying tendon, enabling it to be dissected free of any connective tissues. The area is vascular and haemorrhage is common, but soon controlled with digital pressure.

Fine curved mosquito forceps can then be placed under the tendon and are moved proximo-distally, freeing 1cm to 1.5cm (Figure 8). This is then transected and excised. Skin closure is routine.

Regarding a full digital flexor tenotomy, the dog is placed in a similar position and the assistant again forcibly extends the digit. The incision is through the palmar/plantar skin, beginning 2mm from the metacarpal/tarsal pad and extending distally, exposing the underlying bundles of tendons.

The tendons are incised and none are removed. Several bundles of both the SDFT and DDFT exist, and all must be incised. P1 is identified under the tendons. Skin closure is routine.

NSAIDs are dispensed for seven days. The distal limb is bandaged and the owner is asked to remove the dressings after 24 hours.

The dog is exercised on the lead for 10 days and then free exercise is allowed.

Revision surgery is necessary for:

Revisiting the original site can make identification of the structures difficult due to extensive fibrosis. The author’s preferred site is option three.

A total of 39 dogs with 50 corns had revision surgeries, with 5 dogs requiring a second revision. Corn recurrence was recorded in each of the different tenotomy/tendonectomy procedures, but the most common was after SDF tenotomy.

Following telephone follow-up, 22 of 24 cases were corn free after one year (unpublished data).

Analysis of 305 dogs with 508 corns found 42% had multiple corns, with 30% present at the initial presentation and another 17% developing further corns.

Of the dogs initially presented with a single corn that underwent SDF tendonectomy, 5 dogs developed a further corn in the same foot (13.5%) and 22 dogs developed one in other feet.

The random expectation is that 25% of dogs would develop a corn in the same foot, therefore it would appear that increasing the loading on the other pads does not increase the risk of further corns in the same foot (unpublished data).

SDF tendonectomy is a benign procedure and the author recommends treating all corns in one surgical session. Although the dog will benefit by having tendonectomies on more than one digit in a single foot, lameness may still occur on rough ground from concussive pain on the palmar/plantar skin.

The author recommends SDF tendonectomy as the initial procedure. Full tenotomy at P1 should be reserved for revisions and needs the support of adjacent digits to lessen the risk of PIPJ hyperextension.

Phillipa Williams, Eithne Comerford and the author are conducting a prospective, double-blinded outcome study on SDF tendonectomies.

Also, a PhD projected integrated experimental-computational study assessing long-term biomechanical effects of SDF tendonectomy for corn treatment in greyhounds (Tatjana Hoehfurtner, Prof Comerford, Karl Bates and the author).

Additionally, a call for corn cases in the Liverpool area has been made. Contact Prof Comerford via [email protected]