5 Nov 2018

Pauline Jamieson discusses signs to look out for and approaches to short and long-term management of this condition in dogs.

Figure 1a. Kidneys from a dog with chronic kidney disease showing irregular shape and pitting of the cortical surface. Image: Linda Morrison, The University of Edinburgh

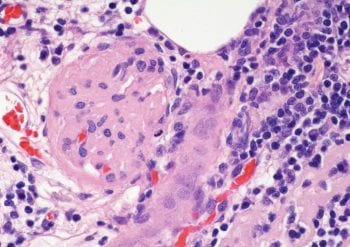

Chronic kidney disease (CKD; Figures 1a and 1b) can be defined as a permanent reduction in renal function that has been present for at least three months1.

It is usually irreversible and, all too often, progressive. However, although many dogs will show a steady progressive decline in renal function with CKD, others will have variable periods of seemingly relative stability followed by sudden declines, either due to a precipitating factor, such as a urinary tract infection (UTI), or for no discernible reason.

CKD in pet dogs in the UK occurs at an estimated prevalence of 0.37% 2. Despite its irreversible nature, it is important to recognise early diagnosis of CKD and appropriate interventions will slow disease progression, and maximise a dog’s quality of life and survival time.

The initial suspicion of CKD may be based on history, clinical signs and/or findings from clinical examination (Panel 1). However, in many cases, suspicion is raised by the discovery of azotaemia on serum biochemistry performed on routine health screening or due to the patient being presented for a seemingly unrelated complaint. Measurement of urine specific gravity (USG) at the same time as serum creatinine is essential as USG less than 1.03 is an inappropriately low urine concentration in an azotaemic dog and indicates inadequate renal concentrating function at that time point.

Efforts should then be made to identify and address any prerenal or postrenal causes of azotaemia and/or acute kidney injury – for example, toxins, infections (especially leptospirosis), pyelonephritis and trauma – before assessing the patient for chronicity of renal disease. Once CKD has been confirmed, International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) staging can be carried out (Panel 2).

A minimum recommended data set (Panel 3) will allow staging of the CKD as well as identification of any co-morbidities and consequences of CKD that require treatment – for example, UTIs, renal secondary hyperparathyroidism or anaemia.

Much discussion has taken place about using serum symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) concentration for earlier diagnosis of CKD as compared to traditional parameters. However, the significance of raised levels of SDMA is best considered together with other clinical and biochemical findings, and the IRIS staging guidelines3 discuss interpretation of SDMA levels further. It may be especially useful in sarcopenic patients where serum creatinine concentrations may underestimate impaired renal function, and some evidence exists that dietary management for CKD in dogs with raised SDMA and normal creatinine levels (IRIS stage I) will improve renal function6. Whether this translates to increased longevity for dogs with CKD requires further investigation.

Proteinuria should be quantified, as a higher urine protein:creatinine ratio (UPCR) is a negative prognostic indicator and a likely risk factor for progression for CKD7. UPCR should be based on at least two samples taken two weeks apart, and after any UTI has been eliminated successfully. However, even in the face of a UTI, a UPCR value greater than two is probably indicative of glomerular disease.

Blood pressure (Figure 2) should also be assessed as – in addition to being a frequent consequence of CKD with potential deleterious effects on retinal, neurological and cardiac health – hypertension probably contributes to progression of CKD8.

Imaging is important for evaluating a dog with suspected or confirmed CKD. Where available, a detailed ultrasound examination will generally provide more valuable information than radiography. Identifying the presence of obstructive uroliths, renal mineralisation, pyelonephritis, renal dysplasia, polycystic kidneys and whether one or both kidneys are involved in any disease process is invaluable in formulating the best therapeutic plan for the individual patient. For example, distension of the ureters and/or bladder suggests postrenal urinary tract obstruction.

In young dogs, dogs with glomerular disease (characterised by proteinuria) or renomegaly, ultrasound-guided renal Tru-Cut biopsy can provide useful information for more accurate prognosis and to better tailor treatment. However, this needs to be balanced against the risk of haemorrhage and further loss of functional renal tissue, and is often contraindicated due to hypertension, anaemia or small kidneys. To obtain maximum information and benefit, in addition to standard histopathology, evaluation by electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry is required, so these samples should be sent to a veterinary nephropathology centre, contacted in advance, for advice on appropriate collection and fixation techniques. Therefore, in many dogs the potential risks of biopsy outweigh the likely benefit for the individual patient. In some cases, a known breed predisposition9 – coupled with consistent findings of age, presentation, findings on imaging and so on – may provide a legitimate presumptive diagnosis and prognosis.

Finally, in anaemic dogs with CKD, iron status should be evaluated, as occult gastrointestinal haemorrhage is common.

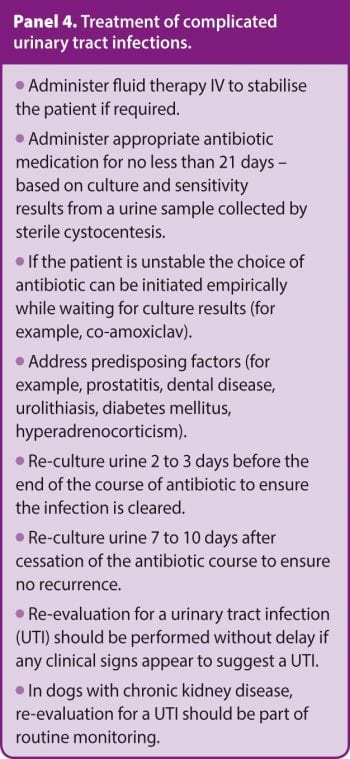

Having obtained the diagnostic data set, any precipitating factors for azotaemia that coexist with CKD (often referred to as acute-on-chronic kidney disease) must be addressed as a priority, as these are often reversible. Dehydration must be corrected, ureteral obstructions relieved (medically or surgically) wherever possible, and UTIs treated with appropriate antibiosis based on culture and sensitivity results of urine collected by cystocentesis. In azotaemic animals, any UTI should be assumed to be potentially pyelonephritis and treated as a complicated UTI (Panel 4).

Lactated Ringer’s/Hartmann’s solution is a suitable choice for IV rehydration therapy, if required, for dogs that present with clinical signs of uraemia at diagnosis or any subsequent decompensation event. In this case, as a guideline, if dehydration is not clinically apparent assume 5% dehydration and replace that volume over four hours10. If point-of-care electrolyte and/or blood gas analysis is available, rehydration can then be tailored further to address specific metabolic disturbances.

Once discharged from the hospital, metabolic acidosis and hypokalaemia or hyperkalaemia requiring medical interventions are uncommon in dogs with CKD. Note current opinion is that, after the fluid deficit is replaced and ongoing losses (for example, from polyuria and vomiting) are met, fluid rates in excess of maintenance requirements (commonly quoted as 66ml/kg/day)10 are likely to be detrimental. Forced diuresis with aggressive fluid therapy to reduce azotaemia should be avoided as volume overload may lead to interstitial oedema of already compromised renal tissue and ultimately cause further kidney damage11.

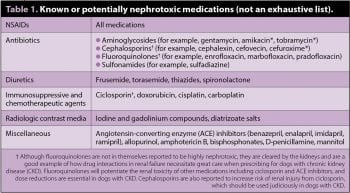

Potentially nephrotoxic medications (Table 1) should be discontinued wherever possible. As dogs with CKD often have coexisting chronic pain (for example, OA), NSAIDs are the most likely agents that need to be reconsidered. In addition to their inherent nephrotoxic properties, hypoalbuminaemia can increase the free fraction of circulating NSAIDs – further exacerbating this potentially detrimental effect.

Many alternative analgesics are available to the veterinary practitioner, so NSAIDs should be used only when other strategies have been exhausted, and then only with caution in a hydrated patient with frequent re-evaluation. Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 selective inhibitors are preferred (for example, firocoxib and robenacoxib) for their lesser adverse effects on the gastrointestinal tract where the potential exists for uraemia gastritis. Both COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors appear to be equally potentially injurious to the kidneys12.

Once the aforementioned considerations have been addressed, thorough communication with owners regarding prognosis, as well as the almost certain requirement for life-long management of CKD and the associated ongoing financial commitment, is essential.

The cornerstone of therapy for CKD is dietary management and a variety of commercial renal diets are on the market designed to address the metabolic derangements that occur. It is important to communicate the rationale for a renal diet to owners as this will significantly improve compliance with the recommendation. Of the modifications encompassed in renal diets (Panel 5), phosphorus restriction and protein content are considered the most beneficial, and have shown improved quality of life and survival times14,15.

Generally, moist foods will help promote fluid intake and maintain hydration, although if the dog prefers dry food it is sensible to continue with this. If possible, introduce a renal diet early after diagnosis of CKD, before uraemic gastritis and poor appetite develop that may contribute to food aversion. For best compliance, it is suggested to introduce the renal diet when dogs are at home and eating well rather than when hospitalised or during recuperation from any decompensation event.

For dogs that will not accept a commercial renal diet, home-cooked diets can be used judiciously. However, owners should be made aware that many of the available recipes (for example, on the internet) are highly likely to be nutritionally inadequate16 and home-cooked diets should only be fed as advised by a qualified veterinary nutritionist and tailored to the individual dog.

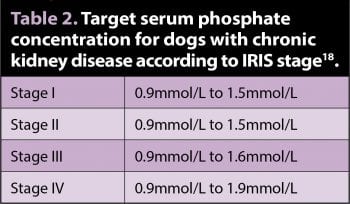

As renal function declines, phosphate retention leads to calcitriol (1,25-dihydrocolecalciferol) deficiency and compensatory renal secondary hyperparathyroidism. Ultimately, as CKD progresses, parathyroid hormone levels are increased in the presence of calcitriol deficiency as well as high serum phosphate levels, accelerating the progression of CKD14,15. Measures to reduce serum phosphate are beneficial and dietary restriction should be the initial intervention. Dietary restriction may take four to six weeks to have maximal effect17, and when assessing effectiveness, phosphate levels should be measured in only on fasting blood samples.

If diet fails to control serum phosphate to the target concentration, give intestinal phosphate binders (for example, calcium carbonate, chitosan and lanthanum carbonate) to effect. These agents will only be effective if given with every meal and with food that is phosphate-restricted. Serum calcium and phosphate concentrations should be monitored every 4 to 6 weeks until the target is reached, and then every 12 weeks (Table 2). If hypercalcaemia develops, calcium salts should be discontinued and a different product given.

Some limited evidence exists that calcitriol* (2ng/kg/day to 3ng/kg/day or 5ng/kg every 48 hours) may prolong survival in dogs in stage III and IV CKD14. However, overdose has potential for hypercalcemia and further renal damage. It is essential serum ionised calcium and phosphate are within reference ranges during administration, so calcitriol should only be used alongside careful monitoring. It should not be given with calcium-containing phosphate binders.

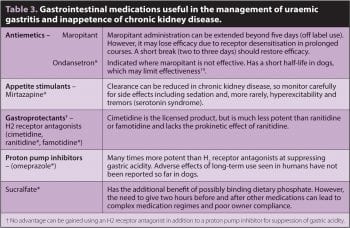

Nausea and poor appetite resulting in insufficient caloric intake, vomiting and weight loss are common in CKD. These clinical signs of uraemic gastritis are frequently the reason dogs are presented for examination and, as well as being a quality of life issue, are often the matter of most concern to owners. Gastric hyperacidity may lead to gastric ulceration, so gastroprotectants are strongly recommended for inappetent or vomiting dogs (Table 3). Anti-emetics are beneficial, but are not in themselves appetite stimulants and the latter can also be prescribed if required.

Oesophagostomy tube placement can be useful while stabilising an inappetent patient with CKD as continued weight loss at this time is likely to lead to a less positive outcome. They are an effective means of delivering food, water and medication that can be used for as long as needed, and most owners cope very well with using them at home.

As well as a consequence of CKD, arterial hypertension can contribute to its progression and so should be treated. The aim is to maintain systolic blood pressure (SBP) between 120mmHg and 160mmHg to minimise the risk of end-organ damage (kidneys, eyes, heart and brain)18. Unless at an “emergency” level (SBP more than 200mmHg, unlikely to be due to anxiety), best efforts should be made to confirm the hypertension is repeatable and measured when anxiety is minimised. Therefore, dogs may need to be hospitalised for a few hours, and habituated to the environment and procedure before a reliable reading can be obtained.

Treatment should commence if persistent hypertension or SBP more than 200mmHg is confirmed (bearing in mind healthy sight hounds may have higher SBP than other breeds [Panel 2]) and the dog is fully hydrated. Unless acute end-organ damage is present (for example, neurological signs or blindness), rapid reduction of SBP is not recommended, so adjustments to medication should be made gradually every one to two weeks.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are the initial choice for treatment given at the standard doses presented in Figure 3 as for proteinuria. These are relatively weak antihypertensive agents, so additional medications, such as amlodipine or hydralazine, may be needed if SBP more than 160mmHg persists once the maximum recommended dose of ACE inhibitors is reached.

Dogs with glomerular disease and protein-losing nephropathy (PLN) require additional consideration to limit proteinuria and protect against thromboembolic events. Underlying diseases may be responsible for this, and so a thorough evaluation is justified if possible with physical examination, screening for infectious diseases based on travel history, and imaging of the thorax and abdomen. Any potential causes identified should be addressed wherever possible.

Inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) in dogs with PLN using ACE inhibitors (in the UK this is off-label use for all available preparations) is established as a standard of care to reduce proteinuria and delay the onset or progression of azotaemia21. The dose and frequency of administration is tailored to achieve a target UPCR of 0.5. However, in most dogs this is not achievable and an alternate target of more than 50% reduction from the baseline level can be considered a therapeutic success20.

Where ACE inhibitors alone fail to achieve this, an angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB), such as telmisartan*, can be substituted or added. It is essential azotaemia, serum potassium and blood pressure are monitored closely as changes in medications and/or doses are made, and that the medication is reduced or stopped if adverse effects occur (Figure 3). This is particularly important where ACE inhibitors and ARBs are used together. While this regime may be effective in reducing proteinuria, the risk of adverse events is increased. A suggested protocol for inhibition of the RAAS in dogs with PLN is presented in Figure 3 20.

Low dose aspirin* or clopidogrel* may protect against thromboembolism and is suggested for dogs with albumin levels less than 20g/L. Neither one has clear superiority over the other with regards to efficacy, so the choice is largely down to clinician preference. Aspirin (1mg/kg/day to 5mg/kg/day)20 has the advantage that it, theoretically, reduces glomerular inflammation. However, clopidogrel (2mg/kg/day) reportedly has more consistency of action22 and may be less likely to contribute to gastrointestinal ulceration in uraemic dogs.

The main cause of anaemia in CKD is inadequate erythropoietin (EPO) production from the kidney. However, iron deficiency should be addressed alongside any EPO analogue therapy (for example, iron dextran* 10mg/kg IM)23. Blood transfusion can be considered if the anaemia is deemed too severe to wait for response to treatment.

Darbepoetin* has a longer effective half-life than other EPO analogues and is suggested to be less likely to result in anti-EPO antibodies and therefore bone marrow red cell aplasia24,25. However, it is still a potential risk and its use should be reserved for dogs whose PCV is less than 20%, or if quality of life is considered to be compromised by anaemia at a PCV less than 25%. A suggested dosing protocol is presented in Panel 61,25. The most commonly reported adverse effect is hypertension, and so blood pressure should be monitored at each injection and appropriate measures taken to address hypertension if required.

The use of anabolic steroids for anaemia is outdated and may be injurious to the liver and kidneys.

Dogs with CKD should be reassessed at regular intervals (see later) so their treatment and medications can be adjusted to best meet their needs as and when their disease progresses. The information collected at initial assessment and diagnosis will provide a baseline for monitoring progression, and further management for CKD can be initiated as and when appropriate. Serum urea, creatinine, phosphate and calcium, blood pressure and urine analysis (USG, sediment examination), should be assessed at a minimum. The need to assess further parameters such as UPCR, urine culture, haematology, serum electrolytes, pH and so on should be based on IRIS stage and the individual patient’s condition.

Initially, reassessment every two to four weeks will allow the response to therapy to be evaluated. Thereafter, revisit intervals should be based on IRIS stage, presence of co-morbid conditions, the potential for complications from medications prescribed and the clinical condition of the dog. For example, if ACE inhibitors, ARBs and/or amlodipine are prescribed for hypertension or proteinuria, reassessments should be more frequent than for a normotensive, non-proteinuric dog with stable IRIS stage I CKD on dietary management alone that might require re-examination once every six months.

If darbepoetin or calcitriol are being used, frequent monitoring every one to two weeks is then necessary. Dogs in IRIS stage II or III CKD generally should be re-evaluated every two to four months, depending on how stable their disease is.

Owners should be made aware of the importance of having free access to clean drinking water at all times and that any sudden decrease in water intake or fluid loss due to vomiting or diarrhoea could signal or precipitate a uraemic crisis warranting prompt veterinary attention for their dog.

Lastly, medications that are renally excreted should be used with caution and only where necessary, and bearing in mind dose or interval adjustment will be required in dogs in IRIS stage III and IV (Panel 7)26.

CKD is a common condition in dogs that is, sadly, irreversible and, in many cases, progressive. Early diagnosis of CKD will provide more opportunity for beneficial interventions, and IRIS staging will allow recommendations to be tailored to the individual patient to delay progression – improving quality and prolonging duration of life.