30 Nov 2022

Kit Sturgess draws on examples of such cases to discuss management in feline patients.

In the UK, it is estimated that around 0.4% to 0.6% of cats have diabetes mellitus (DM; O’Neill et al, 2016; McCann et al, 2007).

The median survival time for diabetic cats is difficult to evaluate, as recent improvements in management have increased the numbers of cats that have transient diabetes. However, in cats that have long-standing diabetes, median survival times of 18 months are reported, but with a very wide range up to 10 years, with nearly half living longer than two years.

Restine et al (2019) reported on 185 cats receiving protamine zinc insulin with a loose control approach, with changes in insulin dose primarily adjusted in clinical response. The likelihood of remission in these cats was 56%, with an overall median survival time of 1,488 days (50 months).

This means the relationship between the owner and the practice is likely to be a long one – making trust, respect and clear communication a priority for successful management.

From the beginning of managing a case, it is important to discuss with the owner the criteria for success; for example, whether the aim is to control clinical signs or to try to achieve diabetic remission.

The appropriate approach will vary and is dependent on the owner-cat combination, with a number of factors needing to be taken into account to decide on the best approach and balance for a particular case.

Key factors that affect the management of diabetes in cats include:

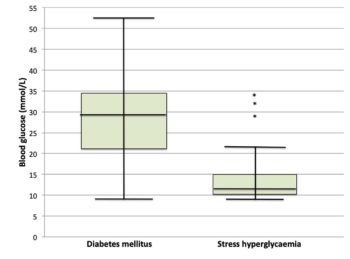

Stress-associated hyperglycaemia is common in cats, meaning hyperglycaemia (even with glycosuria) is not sufficient to make a diagnosis of diabetes (Figure 1). The stress associated with hospitalisation can mean blood glucose curves performed in hospitalised cats may be poorly representative of blood glucose changes at home. However, blood glucose of more than 10.5mmol/L in an otherwise healthy cat should prompt further evaluation (Reeve-Johnson et al, 2017).

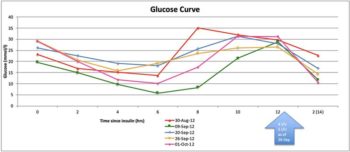

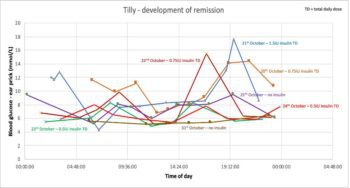

Tilly (Figure 2) – a 13.07-year-old, female, neutered, domestic medium hair cat – presented with a five-month history of unstable diabetes associated with polyuria and polydipsia (PU/PD), polyphagia and weight loss. Her day-to-day water consumption was variable and in-clinic glucose curves gave variable results (Figure 3). Tilly weighed 4.05kg and had received up to 5IU/kg of biphasic insulin twice‑daily.

Haematology

Biochemistry

Blood pressure

Urinalysis

Feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity

Thyroxine

Abdominal ultrasound

Physical examination was unremarkable apart from a grade III/VI left parasternal pansystolic murmur that was not investigated further. Investigations are outlined in Panel 1; no clear other disease was identified.

Based on the glucose curves performed, it was felt duration of action of the insulin was too short and the dose rate may be resulting in over-swing at home. Tilly was started on 1IU of protamine zinc insulin twice‑daily and her diet changed to a high-protein/high-fat wet food.

After two weeks, the glucose curve showed significant improvement and the owner elected to monitor at home. Tilly’s glycaemic control continued to improve and she went into sustained diabetic remission (Figures 4 and 5).

Biphasic insulin may be too short‑acting in some cats and the short-acting component can lead to rapid blood glucose changes worsening over-swing, as postprandial hyperglycaemia in cats can be small.

Time to diabetic remission in cats is very variable, from a few weeks to several months. As glucose toxicity reduces and insulin efficacy increases, cats can appear to become less stable. At this point, over-swing can develop that can appear as apparent resistance – particularly on short-term, in-clinic glucose curves, leading to insulin dose increase worsening the over-swing (as in this case).

Reducing insulin dose rates along with considering the use of a longer-acting insulin dose with a less pronounced peak effect in unstable diabetic cats may result in improved control.

Mimi (Figure 6) – an 11.02-year-old female, neutered Siamese cat – was referred with a history of gradual weight loss over six to eight weeks, lethargy and inappetence; the owner estimated Mimi was consuming around two-thirds of her usual amount of food.

Mimi had vomited once and she was urinating in the house. Haematology, biochemistry and urinalysis already performed showed:

A presumptive diagnosis of DM had been made.

On physical examination, Mimi was quiet, but responsive. She has lost considerable weight (42% of bodyweight), 3.48kg with a body condition score of 2 out of 9. Heart rate was 204bpm; pulse quality was poor.

Mimi purred continually, making thoracic auscultation difficult. Mucous membranes were pale. Mimi has third eyelid prominence associated with enophthalmos and a bilateral purulent ocular discharge. No goitre was palpable. Superficial lymph nodes were within normal limits. Abdominal palpation seemed uncomfortable; one of the loops of small intestine felt thickened.

Causes of weight loss can be broadly categorised into:

Although inappetent, the weight loss was felt to be too great for pure protein calorie malnutrition. DM would potentially account for weight loss associated with excessive calorie loss in the urine and relative insulin deficiency, causing protein and lipid catabolism.

Rapid weight loss, along with the changes in lipid metabolism, could also be causing hepatic lipidosis, accounting for the inappetence rather than polyphagia. The periuria could be an expression of PU/PD. However, the thickened loop of small intestine was of unknown significance, making imaging appropriate, even though no significant gastrointestinal signs had been reported.

Radiography and ultrasound (Figures 7 and 8) showed a linear soft tissue density consistent with an obstruction of the terminal ileum. Ultrasound confirmed a mass lesion distal to dilated bowel in the ileum. The mass lesion had poor wall structure that was primarily hypoechoic.

Mesenteric lymph nodes were enlarged. A small volume, non-septic, peritoneal effusion was present. Mimi’s spleen was prominent and her liver enlarged.

Exploratory laparotomy was performed and the thickened loop of intestine resected (Figure 9) along with an enlarged lymph node; biopsy of the liver was performed.

Histology revealed low-grade hepatic lipidosis and a metastatic mucus-producing adenocarcinoma.

Severe metabolic stress can cause hyperglycaemia that can be of sufficient duration to lead to elevated fructosamine, complicating the diagnosis of DM in cats.

Common

Less common

Where clinical signs (Panel 2) and physical findings are not typical for DM, further investigation is warranted.

Henry (Figure 10a) – a 13-year-old, male, neutered Siamese cat – presented as an emergency with a five-month history of DM. He was receiving 2IU of biphasic insulin every 12 hours.

The owner reported that he was usually moderately PU/PD, but over the past 24 hours, he had stopped eating and drinking, and started vomiting.

On physical examination, Henry was collapsed and poorly responsive. Skin tenting suggested significant dehydration, estimated at 8% to 10%. Temperature was subnormal at 36.5°C with a low heart and pulse rate of 115bpm. Respiratory rate was mildly elevated at 32 breaths per minute, with unremarkable thoracic auscultation. The abdomen was relaxed, non-painful and unremarkable; the bladder was moderately full, kidneys smooth and mobile, and intestines of expected compliance. Henry had not lost appreciable weight over the past six weeks and weighed 4.75kg. Blood pressure was low at 75mmHg mean systolic.

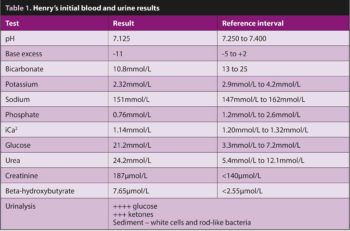

Although a significant number of differential diagnoses was possible, given his known history and evidence that Henry’s circulation was collapsing, a rapid blood screen and urinalysis were conducted to assess his diabetic status and direct initial treatment; results are in Table 1.

Brief abdominal ultrasound to collect a urine sample – and exclude other major pathology – showed a large amount of debris in the bladder lumen (Figure 10b). The initial screen was consistent with diabetic ketoacidosis, potentially secondary to a urinary tract infection with the possibility of pyelonephritis.

Initial therapeutic decisions were:

Rapidly changing acid-base status and blood glucose can have a number of consequences. Key concerns in Henry’s case were:

Blood pressure was continually monitored, along with pulse, respiration and mental status.

Blood glucose, pH, electrolytes, and phosphate levels were initially measured 30, 60, 120 and 240 minutes after the initial triage.

Henry showed a gradual improvement in mentation and demeanour, phosphate supplementation was not required, and urine culture revealed a moderately resistant Escherichia coli.

Henry was discharged after three days of hospitalisation.

Bonnie (Figure 12) initially presented with acute onset lethargy and inappetence. She was jaundiced with significantly raised liver enzymes. A diagnosis of obstructed jaundice secondary to pancreatitis was made.

A year later, Bonnie re-presented with weight loss, PU/PD and polyphagia associated with the development of DM. It was assumed, in Bonnie’s case, that this was most likely due to an absolute lack of insulin (type‑one phenotype), associated with a loss of pancreatic beta cells due to chronic pancreatic fibrosis.

Despite insulin therapy with 5IU of glargine insulin, glycaemic response appeared poor; although, it was unclear whether this was due to over-swing or insulin resistance. Bonnie would not tolerate repeated in-hospital glucose measurements and the owners were unable to perform home monitoring, so a flash glucose monitor was placed. Results from the monitor are shown in Figure 13, indicating insulin resistance.

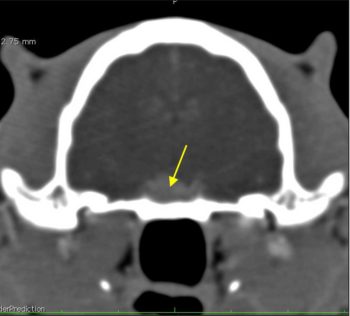

Although insulin resistance can develop secondary to over-swing and can last for several days, the duration of hyperglycaemia in Bonnie’s case was too long. Further investigation was conducted, including measurement of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) to look at the possibility of acromegaly. IGF-1 was more than 2,000ng/ml, consistent with acromegaly, and CT confirmed the presence of a pituitary mass (Figure 14).

Where hyperglycaemia is persistent, differentiating over-swing and secondary insulin resistance can be challenging – continuous glucose monitors are hugely valuable and cost‑effective, allowing blood glucose to be monitored for up to 14 days.

Bonnie had no external features consistent with acromegaly, but physical characteristics are an insensitive rule-out and measurement of IGF-1 is required.

Note in untreated diabetic patients, IGF-1 levels can be suppressed, so measurement should be delayed until insulin therapy has been initiated.

DM is a fascinating, if challenging and sometimes frustrating disease in cats.

Cats with DM are more like people than dogs, and ideally, the aim with all new diabetics is to try to achieve remission, but this requires the ability to establish a good long-term relationship with the owner, and a clear understanding of their priorities and criteria for success.

Recent developments in technology – in the form of easily useable and relatively inexpensive continuous glucose monitoring systems – have provided a valuable additional tool to help us understand our feline DM patients.

All patients teach us something – capturing these learnings is a vital part of developing our clinical practice.