19 Feb 2018

Ariane Neuber provides an update on skin disease, resistant infections and the allergy threshold.

Figure 1. Pustules on the dorsum of a dog with bacterial pyoderma.

Bacterial pyoderma is often seen in companion animals, and the organism most commonly found in these cases is Staphylococcus pseudintermedius.

Strictly speaking, the term pyoderma refers to pus-filled lesions – pustules and cytological evidence of a neutrophilic inflammation. However, bacterial skin disease can present with a variety of lesions, such as erythema, scaling, papules, alopecia, epidermal collarettes, lichenification, draining tracts, nodules, pustules or crusting.

A diagnosis can be easily achieved when the clinical signs are recognised and infection is demonstrated cytologically. Culture and sensitivity testing is not always necessary, but, in the face of growing concern about multidrug-resistant bacteria, is becoming more important.

The clinical signs can vary significantly from case to case. Pustules (Figure 1), draining tracts (Figure 2) and furuncles are classical primary clinical signs. More commonly seen are scaling, alopecia, pruritus, crusts, papules, nodules, lichenification, circular scaling with a rim of erythema (“staph ring” or epidermal collarette; Figures 3 and 4), or an exudate.

The distribution of lesions depends on the underlying disease. Most commonly affected are the ventral abdomen, groin, interdigital spaces (Figure 5), lip fold, axillae, ventral neck (fold), vulvar, anterior elbow, cranial to the prepuce (Figure 6), and occasionally the dorsal and lateral thorax.

The proximal extremities and face are rarely involved. Lesions in these areas are more suggestive of an alternative aetiology – for example, dermatophytosis, a parasite or an autoimmune disease.

As aforementioned, the most common pathogen in cases of bacterial skin disease is S pseudintermedius; however, Staphylococcus schleiferi, Escherichia coli, and Corynebacterium, Enterococcus and Pseudomonas species have also been identified.

Skin is inhabited by a multitude of bacteria of different species.

A study by Rodrigues Hoffmann et al (2014), examining cutaneous bacteria of healthy and atopic dogs with bacterial sequencing, found a highly diverse and variable microbiome. Bacterial populations from each individual examined, and from different body sites sampled, varied significantly (Figure 7). Some of the variability was lost in atopic dogs when compared with healthy individuals (Figure 8).

The presence of a bacterial pyoderma or bacterial overgrowth is usually straightforward. However, much like in cases of otitis, it is important to identify the underlying primary disease to avoid relapses in the future, resolve perpetuating changes, and recognise and address predisposing factors.

Common primary diseases include allergic skin disease, ectoparasites, endocrine disease, autoimmune diseases and keratinisation defects. Therefore, after clearing the active infection, a thorough work-up is indicated to identify which category the patient falls into. Otherwise, an endless cycle of therapy ensues – potentially including systemic antibiotics, with subsequent relapse and repeat need for treatment. This recurrent use of antibiotics is undesirable in view of antibiotic stewardship, as the main risk factor for developing multidrug-resistant infections is repeated use of these drugs.

Perpetuating factors – changes in the skin due to the infection that make the patient more likely to develop the same problems in the future – are also common. Fibrosis, scarring, desquamation disturbances, folliculitis with resulting follicular hyperkeratosis and dilatation of the follicular ostia, and free hair shafts in the tissue following folliculitis – causing a foreign body reaction or corneocyte sequestration in the tissue – are all pathological changes that self-perpetuate the bacterial infection.

Predisposing factors are particularly skin folds. Lip folds, facial folds and vulvar folds, in particular, can be problems areas and surgery may be needed to address this.

Topical therapy can address a variety of factors involved in the pathology, depending on the ingredients in the given product:

Various formulations exist, with shampoo therapy being the most labour-intense if a full body bath is needed. Most, however, involve cleaning and readily treating the whole animal. Once-weekly or twice-weekly shampooing is a good frequency for uncomplicated cases, whereas multidrug-resistant infections will require daily bathing. Between shampoos, topical formulations, such as sprays, gels, wipes or mousses, work well – particularly for areas such as skin folds, interdigital spaces or the chin.

Topical antimicrobials commonly used in veterinary medicine include chlorhexidine, ethyl lactate, antimicrobial peptides and benzoyl peroxide. Topical antibiotics include neomycin, polymyxin, marbofloxacin and mupirocin. Mupirocin is an important antibiotic used in human medicine for MRSA decontamination in the UK and should, therefore, not be used for veterinary purposes. Fluoroquinolones should be reserved for cases when indicated after culture and sensitivity testing.

In the interest of antibiotic stewardship, systemic antibiotic therapy is reserved for cases of deep pyoderma, very extensive lesions or non-responding lesions. If a long course of antibiotics is likely to be needed – for example, in a deep pyoderma – if the patient has not responded to previous courses of antibiotics, or has a history of frequent use of antibiotics or other factors predisposing to resistant infections, a culture should be performed.

It is important to choose a suitable antibiotic at a high enough dose and for a long enough time. The rule of thumb is usually at least one week beyond clinical cure for superficial cases – often at least three weeks – and two weeks beyond clinical cure for deep pyoderma (in cases of podo furunculosis, this can mean weeks or months of therapy).

The first line of antibiotic therapy are agents such as cefalexin, cefovecin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and clindamycin. Fluoroquinolones should only be used if indicated after culture. Some cases benefit from concurrent pentoxifylline to reduce the amount of scarring and improve antibiotic penetration into the infected areas. Once the infection is cleared, systemic glucocorticoids may be helpful in reducing the scar tissue and clearing areas of sterile granulomata.

MRSA or methicillin-resistant S pseudintermedius (MRSP) infections are more commonly seen in veterinary practice. Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas infections are also quite common. Risk factors include:

Hygiene is paramount to prevent spread to other patients. This includes good hand hygiene, using separate kit for patients with known infection that can be suitably disinfected after use, and environmental cleaning/decontamination of potential risk areas, such as keyboards, door knobs, otoscope heads, flea combs, clippers, surfaces in the practice, microscopes, scales, thermometers and stethoscopes.

Ideally, patients with known multidrug resistance should be booked as the final appointment to allow for thorough cleaning afterwards. The pet should be taken straight to the examination room to contaminate as little as possible (avoid the waiting area, for example). MRSP infections are unlikely to cause an issue for humans in the family (however, it is not impossible in immunosuppressed patients particularly), whereas MRSA infections are a likely reverse zoonosis and the affected pet a possible source of reinfection for the human involved. More information can be found by visiting www.wormsandgermsblog.com and www.bsava.com/Resources/MRSA.aspx

The mainstay of therapy is often topical – for example, with chlorhexidine or hypochlorous acid. A study found chlorhexidine to be superior in killing bacteria in vitro, when compared to benzoyl peroxide, ethyl lactate and chloroxylenol (Young et al, 2012). Antibiotic therapy for cases of multidrug-resistant infections should only be used based on culture result (Panel 1).

The use of drugs, such as vancomycin – a last resort drug in human medicine – is controversial and, if considered, should only be used after a strict review.

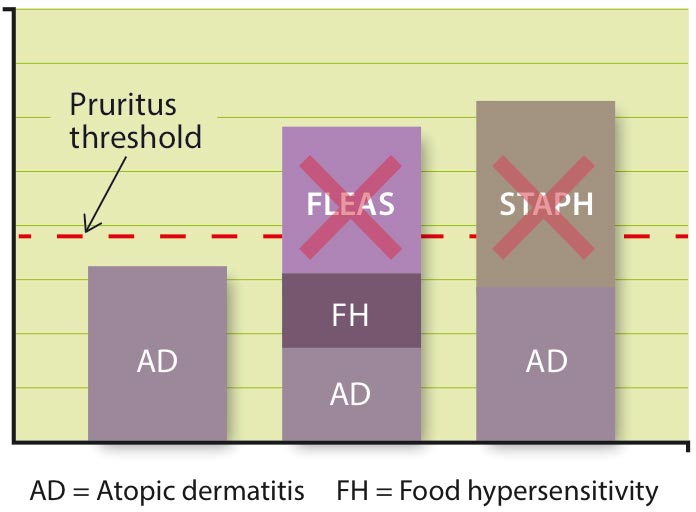

Bacterial pyodermas, such as Malassezia dermatitis, are important flare factors in patients with atopic dermatitis or other kinds of cutaneous allergy. For the theory of the pruritus threshold, each factor contributing to the level of severity is given a fictional itch value. Each patient has a threshold – above this number, they are clinically pruritic (Figure 9). Keeping microbial infections under control is, therefore, a big part of keeping allergic patients comfortable.

Bacterial pyoderma is very common in small animal dermatology and warrants a complete work-up to identify and treat the underlying disease. Infections also play a very important role as flare factors for allergic patients. In mild cases of pyoderma, topical therapy should be used in preference to systemic antibiotics to avoid the emergence of resistance. Multidrug-resistant infections are becoming an issue in veterinary medicine – as they are in the human field – and culture and sensitivity testing needs to be carried out in certain cases to identify whether a resistant infection is present, and which antibiotic is suitable to treat it.