15 May 2023

Hannah Van Velzen, MRCVS, covers some of the most common oral problems found in cats and dogs, and how they may be treated.

Image: © alexei_tm / Adobe Stock

In recent years, the importance of veterinary dentistry in general practice has increased in recognition. This is a hugely positive development, as dental disease occurs extremely commonly in veterinary patients.

More than 80% of dogs and cats above the age of three years1 suffer from dental disease, and it is generally recognised that frequency increases further with age. Symptoms of oral pain and discomfort are unfortunately easily missed by owners and, therefore, the general practitioner must be able to recognise the issues present and actively recommend treatment.

To appropriately advocate for patients, it is essential to be aware of the extent and different indications of dental disease that may be present in the oral cavity, which professionals should be actively looking for during the conscious routine examination.

This article attempts to touch on the most common and significant findings that should prompt further investigation or treatment.

Generally speaking, absence of a tooth occurs either because the tooth never developed or an issue with eruption has occurred.

Issues with eruption are common in many brachycephalic breeds – particularly boxers – and, therefore, the general practitioner should be on lookout for this in particular during routine examination of young animals.

Any missing teeth should prompt further imaging, as unerupted teeth have the potential to develop problems such as odontogenic cysts, which often go unnoticed until significant pathology is present.

Issues with eruption can also be associated with systemic disease, such as in cats with patellar fracture and dental anomaly syndrome.

The author recommends combining neutering procedures in young patients with a quick tooth count at the time of intubation and offering imaging of any missing teeth during the same anaesthetic episode. Unerupted teeth can be extracted or radiographically monitored, depending on the likelihood of pathology development and owner wishes.

True absence of teeth, known as hypodontia (absence of fewer than six teeth) and oligodontia (absence of more than six teeth), likely has at least a degree of genetic background and should never be considered normal. Although it is often of little clinical consequence to the individual patient, breeders should be informed and the owner should be advised against using the individual for breeding.

Identification of missing teeth that were present previously, and for which no record of extraction exists, should also prompt further investigation. Severe end-stage periodontal disease, tooth resorption and tooth fractures that involve total loss of the crown can all present as “missing teeth” during a conscious examination.

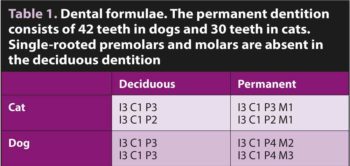

These patients should be evaluated for retained root fragments and any evidence of similar pathology elsewhere in the mouth (Table 1).

Malformed teeth are a product of abnormal tooth development, which occurs prior to eruption. It can affect the enamel, dentin or the full tooth, and results in altered structure, size and/or shape of the tooth.

Hereditary conditions exist, such as amelogenesis imperfecta and odontogenesis imperfecta, but malformations are more commonly secondary to historic trauma, pyrexia, metabolic disease or drug administration.

Gemination describes a specific malformation where a tooth has attempted to split into two. These teeth commonly present with two crowns and a single root. Fusion occurs when two teeth fuse, and share one or multiple roots.

Depending on the type and extent of the malformation, teeth may be more susceptible to endodontic and periodontal disease – especially if the structural integrity of the tooth is affected. Restoration, extraction or radiographic monitoring may be warranted (Figure 1).

Extra permanent teeth, known as supernumerary teeth, can lead to overcrowding and malocclusions.

Particularly in cats and in dog breeds with limited space in the oral cavity, such as brachycephalics and toy breeds, supernumerary teeth can predispose those areas where they are present to pathology. Elective extraction can be offered if problems are expected to occur because of overcrowding.

Persistent deciduous teeth are defined as those present after they should have exfoliated. Exfoliation usually occurs between the age of three to five months and, as a general rule, no deciduous tooth should be present at the same time as its permanent follow up. In retained deciduous teeth, root resorption does not occur, and these teeth should be fully extracted surgically with radiographic guidance to prevent malocclusions and predisposition to periodontal disease.

If concern exists of malocclusion developing, extraction is best performed while the permanent teeth are still erupting, as this may reduce the need for further orthodontic treatment (Figure 2).

Animals with malocclusions should always be assessed for the presence of a traumatic occlusion. Where teeth impact on soft tissues, they cause food impaction, ulceration, erosion and damage to underlying structures, including bone and tooth roots.

Abnormal tooth-on-tooth contact can result in concussive tooth trauma, abnormal tooth wear, painful pulpitis and eventual pulp necrosis.

Malocclusions are classified depending on the positioning of the teeth and jaw lengths relative to one another. Skeletal malocclusions (class II, III and IV), are highly heritable and even considered “normal” in some breeds.

Where the malocclusion is not breed related or a traumatic occlusion exists, the breeder should be informed and the owner advised against using the individual for further breeding. Despite these malocclusions being desirable in some breeds, thorough assessment of these patients is still essential to rule out traumatic occlusion.

Traumatic malocclusion of the deciduous dentition warrants extractions to relieve pain and dental interlock that may interfere with jaw length growth (Figure 3).

A particular presentation of malocclusion is caudal malocclusion in cats, which is common in breeds with tight occlusion such as the domestic shorthair and Persian. In these cats, the cusp of the maxillary fourth premolar tooth (and sometimes also the third premolar) contacts the buccal mandibular mucosa, resulting in inflammation and commonly in development of pyogenic granulomas. Treatment consists of extraction or crown height reduction of the maloccluded maxillary teeth, with or without resection of the granulomatous tissue.

Persistent inflammation and trauma in this area can result in development of periodontal disease of the mandibular first molar teeth, and these should be thoroughly evaluated as well (Figure 4).

Dogs and cats use their teeth for biting, chewing, display, protection and more. As a result, traumatic injuries of teeth are not uncommon, with a large scale study showing an overall prevalence of 26.2% in dogs and cats2.

Fractured teeth occurrance can be uncomplicated or complicated. Complicated fractures expose the pulp directly to the oral cavity, and necessitate either endodontic treatment or extraction. In cats particularly, the pulp extends very far into the tip of the crown of the canine teeth and, as a result, only a small fracture is required to open the pulp cavity (Figure 5).

Although uncomplicated fractures do not directly expose the pulp, they do expose the dentin. This is a tubular structure with direct connections to the pulp. As such, uncomplicated fractures still require assessment and possible treatment.

A recent study showed nearly one-quarter of maxillary fourth premolars with uncomplicated crown fractures had radiographic evidence of endodontic disease, highlighting the importance of full assessment of these type of fractures3.Near-pulp exposures are those where the pink pulp can be seen through the remaining dentin, which indicates only minimal dentin is left overlying the pulp. The closer to the pulp, the more tubules per cm2 and the larger the tubules; therefore, increasing the chances of bacterial invasion (Figure 6).

Even if the tooth does not fracture, blunt trauma can lead to significant pathology. Pulpitis secondary to concussive injury is the most common cause of intrinsic tooth discolouration. Multiple studies indicate a significant portion of these teeth (87.6% in the most recent study4) are non-vital and, therefore, require treatment (Figure 7). Luxation and avulsion injuries (partial or full displacement of the tooth from the tooth socket), are a true dental emergency. These are very painful injuries and should be addressed immediately – especially if the owner wishes to maintain the tooth.

Periodontal disease is arguably one of the most common oral pathologies, with significant local and systemic effects. The degree of periodontal disease wil l vary per individual tooth and thorough examination under anaesthetic, together with dental radiography, is needed to determine the most appropriate treatment option. This may vary from professional cleaning to periodontal therapy to extraction depending on findings5.

Conscious examination findings that may indicate periodontal disease include halitosis, gingivitis, gingival bleeding or ulceration, gingival recession, tooth mobility, draining fistulae (commonly at the height of the mucogingival junction or through the skin), facial swelling or evidence of oronasal fistulae (nasal discharge and/or sneezing; Figure 8).

In cats, type-two tooth resorption (idiopathic resorption) is most common in the mandibular third premolar teeth. If these teeth are undergoing resorption or are visually missing, this should prompt investigation under anaesthetic, as a reasonable chance exists tooth resorption will be occurring in other teeth, as well.

Treatment can consist of extraction, intentional root retention, crown amputation or radiographic monitoring, depending on the extent of tooth resorption and owner wishes.

Type-one resorption is related to inflammatory disease, and is commonly seen in conjunction with periodontal or other inflammatory pathology.

Although well recognised in cats, tooth resorption can also be seen in dogs. The most common type is external replacement resorption, which is often only recognisable radiographically. Other types of resorption do exist and any visual evidence on conscious examination should prompt further investigation.

Gingivitis is nearly always present to some degree in the mouths of cats and dogs. Typical gingivitis should be “appropriate” – that is, directly related to the levels of plaque present on the teeth.

Inappropriate levels of gingivitis should prompt further investigation, as this may be an indication of undiagnosed periodontal disease or other pathology.

Varying oral diseases present with atypical levels of inflammatory disease that extend beyond the mucogingival junction. Canine chronic ulcerative stomatitis presents with ulcerative and severely painful inflammation wherever mucosa comes into contact with plaque. Typical lesions are known as “kissing lesions” or contact mucositis, and are found on the buccal mucosa, where it lies against the teeth. Feline chronic gingivostomatitis presents with inflammation that extends past the mucogingival junction.

Typically, caudal stomatitis is lateral to the palatoglossal folds and the inflammation may also involve the tongue, the palate and the pharynx. In contrast, juvenile hyperplastic gingivitis (which is found in cats less than two years old) is limited to the gingiva only and should, therefore, not be confused with gingivostomatitis, as treatment recommendations are significantly different (Figure 9).

Biopsy is essential for identification of any type of atypical inflammation. This is because many other diseases – particularly neoplasia and autoimmune disease – can mimic inflammatory disease. This includes (but is certainly not limited to) epitheliotropic lymphoma, discoid lupus and squamous cell carcinoma.

Masses and growths present one of the most variable presentations of oral disease. Frustratingly, inflammatory changes, benign masses and malignant masses can all look very similar (even on imaging), and histopathology is required for definitive diagnosis and treatment planning. Fine-needle aspirates are almost always non-diagnostic and core biopsies are, therefore, recommended.

Oral masses are often covered in a layer of inflammatory tissue, so deep biopsies are essential to allow sampling of representative tissue. Radiography may be helpful for guidance of the biopsy site. Many types of oral neoplastic disease respond favourably to surgical resection with appropriate margins, so pursuing biopsy at an early stage rather than adopting a “wait and see” approach can be extremely rewarding (Figures 10 and 11).

Thorough examination of the oral cavity represents a unique opportunity for general practitioners to improve the quality of life of many of their patients.

By adequately identifying indicators of disease, and recommending further investigation and treatment, we can truly make a difference to the lives of our patients.