30 Oct 2018

Luca Ferasin outlines how the diagnostic approach to this common complaint can be complicated by inaccurate interpretations and tackles the controversies of clinical management.

Image © AlexanderStein / Pixabay

Cough is a defensive reflex originating from the respiratory tract and – together with sneezing, expiratory reflex and secretion of mucus – contributes to maintaining a healthy respiratory system.

Indeed, the cough reflex is evoked to expel harmful substances – such as foreign bodies, excessive mucus or debris – from the airways and preserve the normal function of the respiratory tract.

The typical “textbook-defined” coughing reflex is characterised by an initial deep inspiration, followed by a rapid, powerful expiratory act against the closed glottis and, finally, opening of the glottis, closing of the nasopharynx and forceful single expiration through the mouth, accompanied by a typical sound caused by the vibration of the vocal cords.

Conversely, the “expiratory reflex” consists of multiple forced expiratory efforts against a closed glottis not preceded by a deep inspiration.

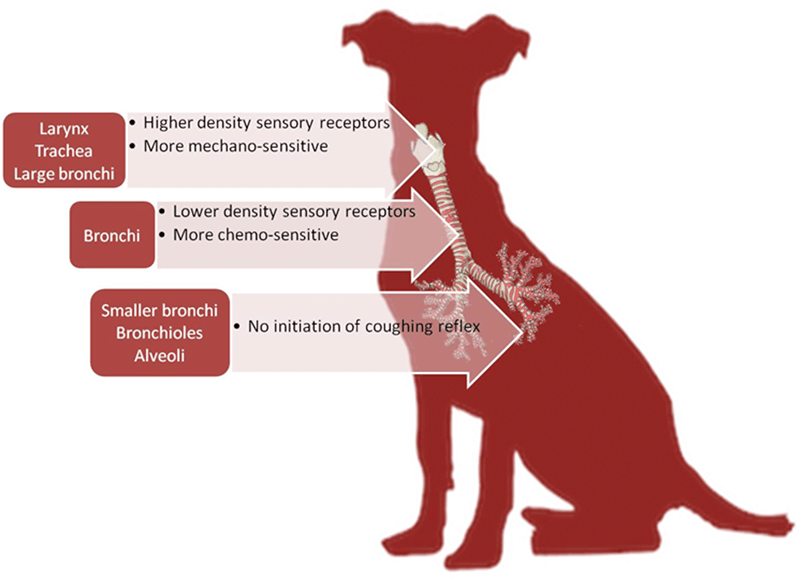

Cough is triggered by stimulation of coughing receptors localised in the larynx, trachea and large bronchi, whereas the expiratory effort is induced by mechanical or chemical stimulation of the vocal cords and often observed in dogs as a “huff” sound, frequently described by the owners as “a bone stuck in the throat” or “clearing the throat”. Interestingly, irritation of smaller bronchi, bronchioles and alveoli does not elicit any form of coughing (Figure 1).

From a clinical point of view, the distinction between classic cough and expiratory reflex is vital since their physiological functions are different. Cough will draw air into the lungs to augment the force of the subsequent expulsive phase, promoting clearance of mucus and foreign material from trachea and bronchi. In contrast, the expiratory reflex – originating from the vocal cords – will prevent the entry of foreign material into the airways.

Therefore, observing a dog with typical cough should suggest lower airway disease – for example, bronchitis, bronchomalacia and lung neoplasia – whereas the presence of an expiratory reflex should indicate an upper airway irritation, such as kennel cough.

Finally, stimulation of receptors in the nasal mucosa can evoke the sneezing reflex, which features a deep inspiration followed by rapid expulsion of air through the nose to eliminate the provoking stimulus. Hybrid responses (associated cough and sneezing) are also possible, and will present with a mixture of coughing and sneezing characteristics.

Cough can be evoked by mechanical or chemical stimulation of cough receptors. The stimulus can be either exogenous (for example, inhalation of a foreign body, smoke or dust) or endogenous (such as inflammatory mediators and bronchial secretions).

However, cough does not originate from smaller bronchi, bronchioles and alveoli. This makes perfect sense – even from a functional perspective – since luminal flow in the lower respiratory tract would be too low to generate sufficient shear forces to clear airway mucus and debris from such sites.

Indoor dogs can be exposed to compounds that can cause coughing, such as dust mites, moulds, fireplace ash, dandruff, litter tray dust, sprays, deodorants and cigarette smoke.

Histological bronchial changes have been reported in several animal models following experimental chronic cigarette smoke inhalation, while biochemical evidence of exposure to passive cigarette smoke has been demonstrated in privately owned dogs.

Coughing dogs living in endemic areas for Dirofilaria immitis (heartworm disease) or Angiostrongylus vasorum (French heartworm) should be tested for these parasites. In young dogs, cough can also be caused by intestinal nematodes – for example, Toxocara canis, Ancylostoma caninum and Strongyloides species – during larval migration. Geographical presence of these parasites changes frequently and rapidly, and it is important to know their potential prevalence in different regions.

Tumours affecting the larynx, trachea, lungs and mediastinum represent an important cause of coughing in dogs, especially when haemoptysis (coughing up blood) is observed.

A relatively common disorder in dogs, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is accompanied by cough in more than 50% of patients.

GORD-related cough in dogs can be caused by microaspiration of gastric contents and a vagally mediated oesophageal-tracheobronchial reflex. At the level of the extrathoracic airway, recurrent aspiration events can lead to laryngeal inflammation and cough. In humans, up to 75% of patients with confirmed diagnosis of GORD present with cough without gastrointestinal manifestations – suggesting that, even in dogs, the prevalence of this cause of cough may be underestimated.

Post-nasal drip syndrome (PNDS) – also termed rhinosinusitis or upper airway cough syndrome – occurs when excessive mucus is produced by the nasal mucosa.

The excess mucus accumulates in the back of the nose and eventually the pharynx, where it drips down the back of the throat – stimulating the laryngeal cough receptors.

PNDS may be caused by chronic exposure of the respiratory tract to particulate matter, allergens, irritants and pathogens.

Although the definition and aetiological entity of PNDS is a subject of controversy in human medicine, chronic rhinitis and sinusitis should be considered as an important differential diagnosis, even in dogs.

A dry persistent cough is reported in approximately one third of human patients following administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. This cough may appear immediately or as late as a few months into the therapy.

The mechanism of ACE inhibitor-induced cough is not completely clear, but it seems to involve protussive mediators bradykinin and substance P (agents normally degraded by ACE and, therefore, that accumulate in the upper respiratory tract or lung when the enzyme is inhibited) and prostaglandins (the production of which may be stimulated by bradykinin).

Resolution of the cough usually occurs a few weeks after cessation of ACE inhibitor administration, although some cases may take a few months to resolve.

ACE inhibitor-induced cough is rarely reported in dogs, but prospective studies to evaluate the occurrence of this potential adverse effect are not available. Therefore, drug-induced aetiology should be considered as a differential diagnosis in dogs receiving chronic ACE inhibition and persistent cough, and a discontinuation trial should be discussed.

Approximately half of dogs with mitral valve disease present with coughing. This cough has often been referred to as “cardiac cough” and its mechanism is frequently explained in different ways.

The most common explanation for “cardiac cough” is the presence of pulmonary oedema, as often reported in veterinary textbooks. However, the cough reflex is not evoked in the deeper respiratory tract (respiratory bronchioles or alveolar space) where pulmonary ooedema occurs. Instead, the presence of fluid in these anatomical areas will almost inevitably present with tachypnoea and/or dyspnoea.

Another explanation for “cardiac cough” is the mechanical stimulus of bronchial cough receptors caused by the enlarged heart and, in particular, the enlarged left atrium, which is anatomically located just beneath the main stem bronchi. However, puppies are very rarely observed with significant congenital cardiac defects and severe cardiomegaly presenting with coughing.

Since airway disease is more commonly observed in older dogs, cardiomegaly may be a more likely cause of cough in patients with pre-existing airway disease due to a summative stimulation of coughing receptors caused by the two comorbidities, compared with young individuals with a healthy respiratory system. Indeed, left atrial enlargement is associated with an increased risk of cough in dogs with chronic degenerative mitral valve disease, and a tenfold increased risk of coughing exists if left atrial enlargement and airway disease coexist, even in the absence of pulmonary oedema.

Therefore, the term “cardiac cough” is a misnomer since cough originates from the airways – even in cardiac patients. For this reason, in cardiac patients presenting with a cough, the differential diagnosis should always include other pathologies, such as infectious tracheobronchitis, tracheal collapse, bronchomalacia, GORD, PNDS and neoplasia.

Colloquially, cough is often classified as “productive”, “wet” or “chesty” when associated with expectoration of large amounts of sputum, often swallowed after coughing.

Conversely, a cough is classified as “dry”, “honking” or “hacking” when little or no production of phlegm occurs.

However, this distinction is not particularly useful for a diagnostic investigation since substantial overlap exists between the two forms. Similarly, character and timing of a cough is not diagnostically helpful since diagnostic approach and outcome is almost identical, regardless of whether the cough is productive.

Furthermore, the observation of a “nocturnal” cough is often misleading because a coughing dog can make its owners wake up, making such cough more noticeable at night.

Haemoptysis should prompt urgent investigations since it could be the first clue as to the presence of lung tumours, clotting disorders, pulmonary thromboembolism, heartworm disease or lungworms.

Physical examination of a coughing patient is of paramount importance. For example, nasal and ocular discharge, accompanied by frequent licking and swallowing, could be an indication of PNDS associated with rhinitis and sinusitis.

A cough easily elicited by gentle tracheal palpation suggests coughing receptors are already stimulated by an underlying condition where the stimulus is not sufficient to reach a threshold for continuous coughing. Therefore, the widely used concept of “positive tracheal pinch” is incorrect because this manoeuvre does not provide a “positive/negative” response.

Auscultation over the larynx and trachea can reveal stridors or clicks in coughing animals with laryngeal paralysis or tracheal collapse. Thoracic auscultation often reveals stridors, rhonchi, crackles and wheezes, which are suggestive of airway disease at different levels in the respiratory tract.

Inspiratory crackles can be present in coughing dogs with chronic interstitial lung disease or “lung fibrosis”, especially in West Highland white terriers and other terrier breeds. Although crackles are commonly reported in veterinary literature as an indication of alveolar pulmonary oedema, the most likely mechanism of crackle generation is sudden airway closing during expiration and sudden airway reopening during inspiration, as happens more commonly in parenchymal (for example, pneumonia) and interstitial disease (for example, lung fibrosis).

Furthermore, rhonchi associated with bronchial disease are often mistakenly reported as crackles by clinicians. Chest percussion can reveal a horizontal line of dullness consistent with pleural effusion, sometimes associated with cough. Thoracic masses, often responsible for cough by mechanical compression, can sometimes be identified by chest percussion.

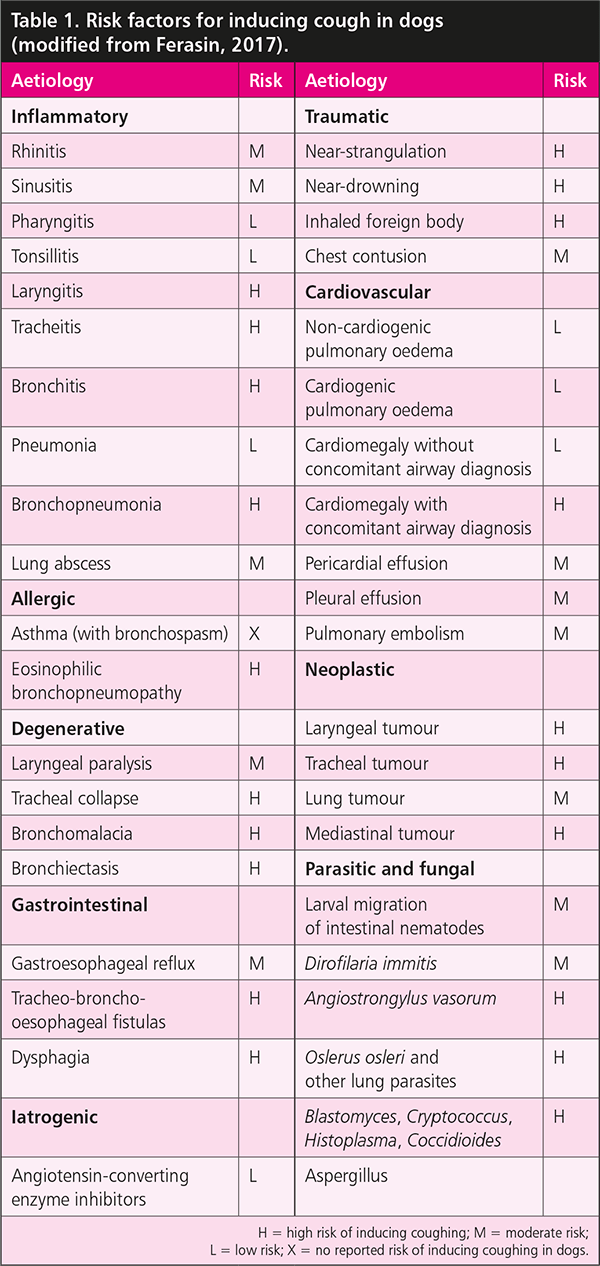

Risk factors for inducing cough in dogs are listed in Table 1.

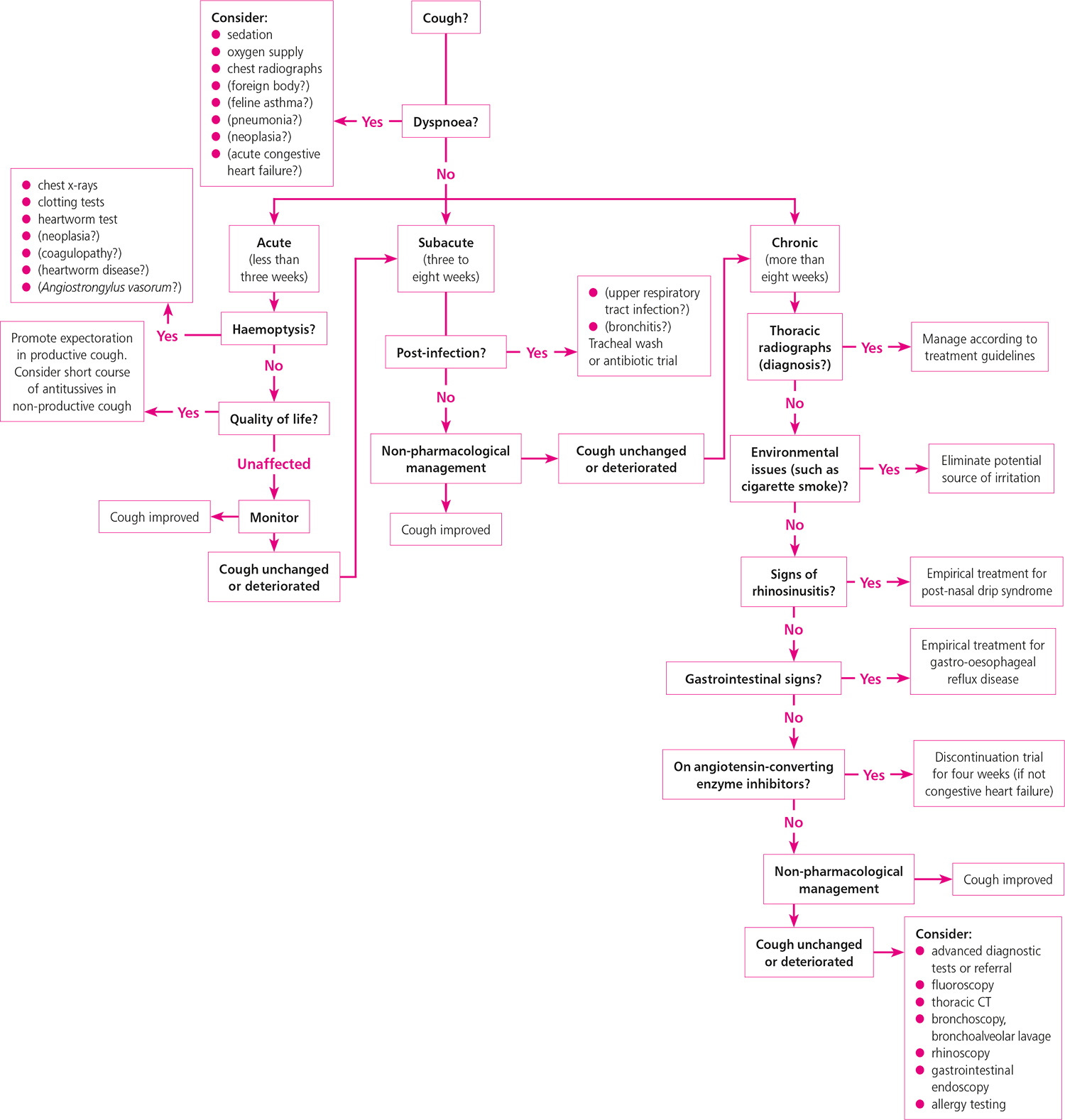

Cough itself is not a life-threatening condition; however, when it occurs hyperacutely, it may indicate a serious underlying problem – such as inhalation of a foreign body with airway obstruction, coagulopathy, near-drowning and smoke inhalation – and should prompt a rapid investigation. A suggested diagnostic plan is shown in Figure 2.

Laboratory tests should include haematology, which may reveal neutrophilia in inflammatory diseases, or eosinophilia and basophilia in parasitic or fungal infections.

A faecal Baermann test should be considered to aid identification of different types of lungworms. Antigen tests are also available for detection of D immitis and A vasorum, and their use is recommended in all coughing animals living in endemic areas.

Thoracic radiographs are recommended at an early stage, as a significant abnormality will alter the diagnostic plan and avoid unnecessary investigations. However, radiographic examination may fail to identify dynamic airway collapse, infectious tracheobronchitis or parasitic infections.

In the routine evaluation of chronic cough, bronchoscopy offers a poor diagnostic yield. Such investigation should be reserved for selected cases, such as inhaled foreign bodies, dynamic or static airway collapse, chronic bronchitis and lungworms. Furthermore, bronchoscopy provides the opportunity for airway sampling by either mucosal biopsy or bronchoalveolar lavage.

Thoracic CT scanning is becoming widely available in veterinary medicine, and allows more accurate diagnoses of diffuse parenchymal lung disease, bronchial disease and foreign bodies that may have not been identified on thoracic radiographs.

Additional diagnostic investigations may include fluoroscopy, gastrointestinal endoscopy, rhinoscopy and allergy testing.

Cough is a protective mechanism and should never be suppressed, with the exception of persistent coughing interfering with exercising, eating, drinking and sleeping, and, therefore, affecting the patient’s quality of life.

Cough can also spread infections and, by further irritating the airways, it may initiate a vicious circle of cough-induced cough. Therefore, cough suppression should be limited to these cases.

If a primary cause of coughing is identified – for example, removal of an inhaled foreign body or antibiotic treatment in case of bacterial bronchopneumonia – this should be immediately addressed. However, in most cases, the initial approach is empirical, and aimed at relieving airway obstruction and the source of irritation as follows:

Avoidance of potential irritants – such as cigarette smoke, dust, deodorant sprays and house cleaning products – should be considered. Carpets should be vacuumed frequently and clean cotton sheets should be used to cover the dog’s bed.

Fat that accumulates in the chest reduces lung volume and causes compression of the airways, stimulating coughing. Conversely, weight reduction will improve respiratory and cardiovascular functions with excellent results.

A harness should be worn instead of a collar when the dog is walked on a lead, to reduce the stimulation of mechanoreceptors at laryngeal and tracheal levels.

Gentle, long walks can promote dislodgement of bronchial secretions – and opening of small airways – by promoting increased lung volumes associated with a standing position.

Environmental humidification overnight helps bring up mucus from the lungs, bronchi and trachea because it thins the mucus and lubricates the irritated respiratory tract. Several ultrasound humidifiers (“cool mist”) are available and can be installed in the area the dog sleeps. The usefulness of chest coupage is somewhat controversial, but may help dislodge deeper secretions.

If improvement is not observed following the aforementioned conservative management, antitussive therapy should be carefully considered, although it should be emphasised scientific evidence is lacking:

An inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) – such as fluticasone, beclometasone and budesonide – acts directly on the airway mucosa, reducing local inflammation. Since ICSs are minimally absorbed, negligible side effects are expected. ICSs are administered using dedicated spacers with a mask.

Expectorants – such as guaifenesin – increase the volume and reduce the viscosity of airway secretions, therefore improving the efficiency of cough to remove such secretions.

Mucolytics – such as acetylcysteine, ambroxol and bromhexine – modify the structure of mucus glycoproteins and reduce mucus viscosity. Their use should be restricted to a few special instances, such as liquefying thick, tenacious, mucopurulent secretions.

Cough suppressants – such as butorphanol, codeine, hydrocodone and dextromethorphan – are centrally acting antitussives that inhibit the cough reflex by acting on the medullary cough centre. Most cough suppressants have sedative effects that may be desirable in painful, persistent cough. The clinical usefulness of dextromethorphan in children has been questioned and little information is available about its efficacy in small animals.

Bronchodilators – such as inhaled salbutamol/albuterol, theophylline, aminophylline and terbutaline – relax contracted airways and smooth muscle, and are only useful to treat bronchospasm. However, naturally occurring bronchospasm has not been convincingly demonstrated in dogs, so bronchodilators should be avoided at least until their clinical usefulness has been scientifically documented.

Some drugs listed are used under the cascade.