6 Apr 2021

Albane Fauron, BVetMed, MRCVS looks at the aetiology, clinical signs, diagnosis and treatment of five prevalent pathologies

Hip dysplasia, elbow dysplasia, shoulder osteochondrosis, medial patellar luxation and panosteitis represent the five conditions most commonly diagnosed in young canine patients.

This article offers a concise overview of the aetiology, clinical signs, diagnosis and treatment of each of these pathologies.

Hip dysplasia (HD) is abnormal development of the coxofemoral joint, resulting in dysplasia of the femoral head and acetabulum, as well as laxity of the joint capsule and surrounding soft tissues. In turn, those abnormalities result in mild to severe joint instability. In severe cases, cartilage erosion and subchondral bone fractures can be present.

Disease progression typically leads to inflammatory changes within the joint, as well as OA (degenerative joint disease, or DJD). HD usually occurs bilaterally.

HD is a common and hereditary condition. However, environmental factors such as diet and exercise are thought to have profound effects on the phenotypic expression of DJD in individuals genotypically predisposed to HD.

The genes do not affect the skeleton primarily, but rather the cartilage, supporting connective tissues and muscle mass of the hip region (Brinker et al, 2016a).

HD may develop in any breed of dog, but is more prevalent in medium and larger breeds. The German shepherd dog and St Bernard are species particularly at risk. Other species with higher incidence of HD include the Labrador retriever, the golden retriever and the Rottweiler.

The disease follows a bimodal model with two clinical groups of dogs:

Young dogs between 4 and 12 months of age – these dogs typically show sudden onset of unilateral disease (more rarely, bilateral), including difficulty in arising and reluctance to walk/run and climb stairs. They classically appear sore in the hindlimb(s). Unwillingness to exercise often results in underdeveloped thigh/pelvic muscles. Owners may describe a bunny hoping gait, where both hindlegs move in synchrony when running.

Animals older than 15 months of age – older dogs present with a more chronic clinical picture. Lameness is usually bilateral more than unilateral. Clinical signs are more typical of DJD – that is, soreness and lameness after prolonged exercise, as well as reduced range of motion of the joint. Over time, pelvic limb muscles atrophy greatly, while shoulder muscles tend to hypertrophy because of cranial weight shift and increased use of the forelimbs.

HD diagnosis is based on clinical signs, including difficulty in rising, pain and, in young dogs, a positive Ortolani sign. This latter finding is rarely present in older, larger dogs because of both fibrosis of the joint capsule and shallowness of the acetabulum.

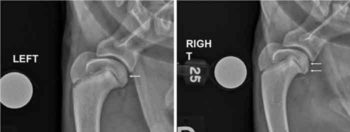

Definitive diagnosis is based on radiographic findings, which include joint subluxation, joint incongruency (shallow acetabulum, flattening of the femoral head) and early degenerative changes (Figures 1 and 2).

Dogs showing no signs of pain (or mild and intermittent signs) can be treated conservatively (weight loss, joint supplements, physiotherapy, analgesia). In young growing animals with severe clinical signs, triple pelvic osteotomy (performed at 4 to 8 months of age) or pubic symphysiodesis (performed at 12 to 16 weeks of age) may be carried out.

Total hip replacement, and femoral head and neck ostectomy are typically reserved for animals that have stopped growing (that is, at least 15 months old), show clinical signs and have failed to respond to conservative management.

Elbow dysplasia (ED) is an umbrella term for several conditions of the elbow, including ununited anconeal process (UAP), fragmented medical coronoid process (FCP), osteochondrosis and joint incongruity. Patients commonly present with one or two conditions concomitantly.

UAP denotes a failure of the anconeus to fuse with the olecranon by five months of age. The condition can be bilateral. FCP is a fragmentation of the medial coronoid process of the ulna. The majority of cases are bilateral. Clinical signs may be evident as early as five months of age.

Osteochondrosis/osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) of the medial humeral condyle (see shoulder OCD for more details on OCD) typically presents as a triangular subchondral defect on the medial aspect of the humeral trochlea, generally visible by five to six months of age. Elbow incongruity denotes poor conformation of the joint, with radioulnar incongruity being the most common form of this condition.

All four conditions have a genetic origin. Elbow incongruity can also be secondary to physeal trauma.

UAP is found primarily in large-breed dogs – particularly German shepherd dogs, Rottweilers and St Bernards. The same breeds are also at risk of FCP and OCD, in addition to Bernese mountain dogs and Labrador retrievers. Elbow incongruity is more common in chondrodystrophic breeds.

Clinical signs are unilateral or bilateral lameness and elbow joint effusion. Pain on deep palpation and elbow flexion/extension is commonly seen with FCP and (although less frequently) with OCD.

All conditions are most commonly diagnosed by radiography. A flexed lateral view typically reveals UAP or, in severe cases, a completely detached anconeal process. FCP radiographic signs are non-specific.

Typically, the first radiographic sign is the appearance of an osteophyte at the anconeal process (predilection site). Osteophytosis can also be seen at the cranial aspect of the radial head (Figure 3e). Sclerosis of the trochlear notch is also common. A lateral view may also reveal blunting of the medial coronoid process (Figures 3a and 3b). CT is particularly useful in mild cases (Figures 3c to 3e).

In OCD cases, a diagnosis is made based on the presence of a triangular subchondral defect on the medial aspect of the humeral trochlea on a standard craniocaudal view (while the dog is five to nine months old). In cases of elbow incongruity, a mediolateral flexed view is the most useful diagnostic tool.

For UAP, depending on cases, removal of the anconeal process or anatomical reduction and screw fixation produce good results.

For OCD, initially, conservative (that is, non-surgical) therapy can be initiated (weight loss, joint supplements, physiotherapy, analgesia). In cases that fail to respond to conservative management, or severe cases with obvious fragmentation, subtotal coronoidectomy is performed.

FCP cases are frequently bilateral and surgery may be carried out on both legs at the same time. The prognosis is good when surgery is performed before significant OA is present.

In OCD cases, flap excision is advocated (see shoulder OCD). Typically, the prognosis is good if surgery is performed at up to nine months of age. Finally, elbow incongruity is addressed with different surgical technique depending on the underlying cause (for example, short/long ulna).

OCD is a disturbance of cell differentiation in joint cartilage. Failure of ossification of cells in the calcifying zone leads to an expansion of the hypertrophic zone, resulting into areas of cartilage of increased thickness. Cells within these areas, including cells deep within the cartilage, eventually die, leading to a defect at the cartilage/subchondral bone junction.

Normal daily activity may cause OCD to progress such that a vertical cleft breaks through the surface of the cartilage, creating a flap of articular cartilage – the condition is then termed OCD. This is typically at the stage that lameness occurs (typically five to seven months of age). OCD of the humeral head is the most common presentation of this pathology. Affected animals typically have a bilateral symmetrical distribution of lesions (Ytrehus et al, 2007).

The aetiology is failure of blood supply (essential for ossification of mineralised cartilage) to the humeral head. The underlying cause for this is thought to be multifactorial, and includes diet (particularly increased calcium intake), rapid growth and genetics.

Large-breed dogs are most commonly affected and include the Labrador retriever, Rottweiler, border collie and great Dane (Johnston, 1998; Olivieri et al, 2007).

Clinical signs include weightbearing lameness (mild to severe) of the affected forelimb, most notable after rest preceded by heavy exercise. Pain on shoulder palpation, extension and flexion is variable.

Diagnosis is based on clinical signs and radiographic findings, which typically include a flattening defect of the caudal humeral head on a straight lateral view (Figure 2).

When recognised early and before flap formation (four to six months old), OCD may be treated with rest and diet change. However, once a flap has formed and/or separated, healing will not occur.

Removal of the flap, either arthroscopically or open, is recommended for return to function and carries an excellent prognosis. The prognosis is excellent, especially if treated before 12 months of age.

Medial patellar luxation (MPL) typically results from skeletal abnormalities affecting the alignment of the quadriceps mechanism (coxofemoral joint conformation, distal femoral torsion and angulation, deviation of the tibial crest, quadriceps atrophy, shallow trochlear groove). In turn, these abnormalities push the patella medially and outside the trochlear groove.

MPL is graded on a four point scale:

Grade I – the patella can be luxated manually, but returns to its normal position within the trochlear groove when released.

Grade II – spontaneous luxation occurs during a normal range of motion, but the patella normally resides within the trochlear groove. Clinical signs may or may not be present – the most typical of which is a non-painful, “skipping” type of lameness, where the dog will intermittently limp and hold the leg up for a few steps before returning to normal.

Grade III – the patella is permanently luxated, but can be reduced manually. More severe deformities of the tibia and femur may be present. A shallow trochlear groove may be palpable.

Grade IV – permanent, non-reducible luxation of the patella. Severe tibial rotation, shallow/flattened trochlear groove and displacement/atrophy of the quadriceps muscle group may be present.

MPL is a developmental, rather than traumatic, condition. The overrepresentation of certain breeds suggests a genetic component in the disease aetiology, which is further supported by the high prevalence of bilateral cases (LaFond et al, 2002; Alam et al, 2007).

While the vast majority of MPL cases are developmental in origin, incidences of traumatic MPL have been reported (Remedios et al, 1992; Hayes et al, 1994).

MPL may develop in any breed of dog, but is more prevalent in small‑breed dogs – especially Pomeranians, Chihuahuas, poodles, Maltese, cavalier King Charles spaniels and Yorkshire terriers.

Age at presentation varies greatly, with dogs diagnosed with MPL as young as 3 months of age and as old as 16 years of age (Hayes et al, 1994; Alam et al, 2007). However, the majority of cases begin to show clinical signs by 5 or 6 months of age.

Clinical signs for young dogs depends on the grade of MPL. Neonates and older puppies often manifest clinical signs of abnormal pelvic limb carriage and function as they begin to ambulate; these dogs typically suffer from a grade III to IV MPL.

Young to mature animals might have exhibited abnormal or intermittently abnormal gaits (“skipping gait”) all their lives, but now present due to worsening symptoms; these dogs typically suffer from grade II to III MPL.

Diagnosis is reached by orthopaedic evaluation: the patella is located, isolated and the stifle joint put through a range of motion (flexion, extension, internal and external rotation). The foot is internally and externally rotated while trying to push the patella medially to identify the grade and direction of luxation: a popping sensation should be felt as the patella luxates and reduces.

Once orthopaedic examination has confirmed MPL, radiological examination is critical in the identification of any underlying skeletal abnormality (Figure 4). However, in cases of grade I or II, or III MPL, positioning of the patient may result in MPL reduction – emphasising the importance of physical examination.

As a general rule, grade I cases are typically non-clinical and do not require treatment. Grade IV cases always need corrective surgery. The decision to perform surgery in grade II and III cases depends on the severity of clinical signs.

Surgical treatment typically includes the combination of both soft tissues (that is, joint capsule imbrication or release) and bone techniques (that is, sulcoplasty, tibial tuberosity transposition). As previously mentioned, patients with severe MPL should always be assessed for additional deformities. For example, failure to recognise and address pronounced distal femoral varus as an underlying cause for MPL (Figure 4) will result in recurrence of luxation and suboptimal limb function postoperatively.

Panosteitis is a self-limiting inflammation of bone marrow in long bones. This is a common condition in young, large-breed dogs.

Aetiology is unknown. Viral infection, metabolic disease, endocrine dysfunction, autoimmune mechanisms, parasitism and hereditary factors have all been proposed as potential contributing factors to the disease (Brinker et al, 2016b).

Panosteitis is more prevalent in German shepherd dogs and basset hounds. Males are affected four times more often than females (Barrett et al, 1968).

Clinical signs include acute onset lameness with no history of trauma. The lameness may vary from partially weightbearing to non-weightbearing and lasts from a few days to several weeks.

As other limbs may become involved (53% of cases; Brown, 1975), the initial lameness may become a “shifting” lameness. Long bone palpation will elicit a pain response. Affected dogs are typically 5 to 12 months old by the time of presentation. Bouts generally resolve by 2 years of age.

Radiographs or CT of the affected limb(s) typically show patches of increased density within the medullary cavity (Figures 5 and 6). Occasionally, the entire medullary cavity may become involved. In a third of cases, the periosteum may become involved as well.

Note: panosteitis may coexist with osteochondrosis, which is also common in young, large-breed dogs. Identifying the cause of lameness in a dog affected with both conditions concomitantly may be challenging.

Additional imaging, such as MRI or CT, will help in differentiating both conditions. For example, in the case presented in Figure 6, a CT scan was performed directly without radiographs to rule out elbow disease and diagnose panosteitis at the same time (as previously mentioned, CT is particularly useful in cases of mild elbow disease).

Treatment is mainly aimed at relieving pain, and includes rest and analgesia (mainly NSAIDs). No treatment has been shown to hasten resolution of panosteitis (Muir et al, 1996).