13 Nov 2017

Karen Walsh discusses studies into a variety of therapeutic options regarding canine and feline patients with this condition.

Evidence exists that physical therapies – including physiotherapy – can have a positive impact on quality of life in small animal patients with chronic pain. IMAGE: Fotolia/Lilli.

Chronic pain is difficult to treat in human and veterinary patients. This difficulty is partly due to the problems with pain assessment. A multimodal approach is essential and should include physical, adjunctive and drug therapy.

Many of the drugs used are not licensed for the species or condition, and this should be discussed with the owner, while novel therapies require further research to give an improved idea of benefits and complications.

Treatment for, and understanding of, chronic pain is constantly evolving. This article will look at some of the newer modalities and approaches that may be underused, to allow the general practitioner to make an informed decision about treatment.

In a 2016 review published in the British Medical Journal, it was estimated a third to half of the UK adult population was affected by chronic pain (Fayaz et al, 2016). The large variation in prevalence reported may be, in part, due to the difficulty in quantifying and identifying this type of pain.

It is likely many of our patients suffer from chronic pain – particularly as life expectancy increases. Just as identification is difficult, so too is assessing response to treatment, which further complicates management. Many drug therapies are unlicensed, and the numbers involved in many studies mean evidence-based recommendations are unlikely to be established in the near future. Managing patients with chronic pain requires frequent discussion and adequate counselling of owners throughout the treatment time.

This article will concentrate on newer advances and treatments. Many will not be evidence-based; however, first line treatment will usually start with NSAIDs and joint supplementation, as well as investigating whether surgical treatment is an option.

Chronic or maladaptive pain can be the result of an ongoing noxious stimulus that is sustained by neuroplastic (sensitisation and alterations in receptors) changes well after healing. No obvious inciting cause may exist for chronic pain. In humans, chronic pain is described as more severe and unrelenting, and may not be explained by the identifiable cause.

The clinician will need to convey to the owner the difficulties inherent in treatment, as it can often be very time consuming and frustrating to treat. The mechanisms (Voscopoulos and Lema, 2010) associated with chronic pain are described in detail in other texts.

Detecting/measuring chronic pain is perhaps the biggest challenge in its management. Our patients are not able to self-report, so it is up to pet owners and veterinary staff to interpret how a pet feels. Health-related quality of life (QoL) questionnaires appear to allow an interpretation of the patient’s well-being as a whole, and may make it easier to assess efficacy of treatment and, possibly, initiate therapies earlier in a disease process.

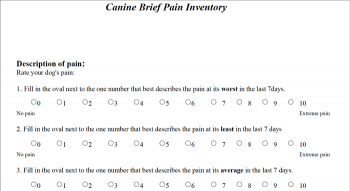

Just as in human medicine, a number of scoring systems have been used in the literature to assess chronic pain in dogs (Brown et al, 2008; Wiseman-Orr et al, 2004). Many of these use behavioural indicators to allow the pet owner to answer questions about QoL. The Canine Brief Inventory of Pain (available at www.vet.upenn.edu/research/clinical-trials/vcic/pennchart/cbpi-tool) has been used in some research papers to assess efficacy of treatments and patient QoL. Meanwhile, a relatively new system is Newmetrica (www.newmetrica.com), which uses questions to assess four domains: energy, happiness, comfort and calmness.

This system generates an output that looks at the overall well-being of the pet, and an interesting aspect is it seems to help measure health improvement and decline. It will be interesting to see how widely scoring systems like this will be embraced in general practice.

Importantly, the aspect of assessment both these scales look at is QoL and interpretation of how the pet “feels”, not a quantifying of the degree of pain.

When embarking on treatment of chronic pain, it is important to discuss the aim of the treatment programme. Many owners are mostly concerned with QoL, rather than duration, but this should be discussed when deciding on a treatment programme.

Using one of the assessment tools may help establish some objective goals for treatment, such as the brief inventory of pain (Brown et al, 2008) or the Newmetrica system. Supplying a copy to the owner at this time might also improve compliance and follow-up.

It is almost inevitable chronic pain patients will require multimodality treatment, which includes drug, physical and adjunctive therapies. A holistic approach is important in many of these elderly patients, as they will often have multiple medical conditions that influence QoL.

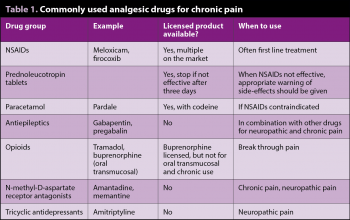

Table 1 shows an overview of commonly used drug treatment options.

Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) is a lipid molecule available as a food supplement in the UK and Europe without prescription. In humans, PEA has been demonstrated to reduce inflammation and pain in acute and chronic settings. It appears in chronic pain PEA may directly intervene in nervous tissue alterations responsible for pain.

A metanalysis by Paladini et al (2016) looking at the effects of micronised and ultramicronised PEA indicated sufficient evidence that PEA improved pain scores over time, with a maximal effect achieved 60 days after commencing therapy. Little, if any, side effects appeared associated with its use.

The veterinary literature has been confined to its effects on experimental models of OA, where initial results may be promising (Britti et al, 2017).

Cannabinoids (CBs) have been of interest to medical pain specialists for some time and it is likely, as their profile increases, vets will be asked about their possible use in companion animals for pain relief. Preclinical studies in a wide variety of pain models have demonstrated these drugs may have a dissociative effect on the pain pathways.

Some synthetic CBs have been licensed for specific uses in humans; the two active CBs with the strongest evidence for analgesia are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). THC also has psychoactive effects.

Action is via interaction with receptors CB1 and CB2. CB1 is mainly found in the brain, spine, visceral organs and adipose tissue, and central CB1 receptors are also thought to be involved in the psychoactive effects. CB2 is mainly found in haemopoietic and immune cells, and microglial cells in low levels. The CB2 levels appear to increase in microglial and neuronal cells in the face of injury and inflammation.

As with other types of analgesics, it is important to look at the type of pain being treated, as a metanalysis in human medicine did not find significant evidence to advocate the use of CBs in neuropathic pain. However, the use of these drugs needs to be balanced against the possible side effects, such as psychosis/behavioural changes.

Although interest exists in their use in our species, no licensed products are, as yet, available, and clinical dose response studies have not been published. Much of the published literature is in relation to inadvertent overdose, rather than clinical use. It is possible to buy products containing non-psychoactive CBD as a food supplement in the UK, which should not have any psychoactive properties. However, little, if anything, is known about the actual clinical efficacy of these products, or the dose required for effect.

Ketamine has been used for many years as an anaesthetic agent and, more recently, as an analgesic therapy for acute pain. Amantadine and memantine are both oral N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists that have some use in treatment of chronic pain.

Of the two, amantadine has some more evidence regarding use and dosing. In one placebo-controlled trial amantadine 3mg to 5mg once daily was used in conjunction with meloxicam and was found to improve pain scores compared to a placebo. Generally, it has been prescribed once daily, but a study in greyhounds indicated twice-daily dosing may be appropriate. It would be important, though, to repeat this in other breeds of dogs.

Memantine has been used anecdotally as an analgesic – especially in patients that did not respond to amantadine. However, veterinary literature has, so far, been regarding its use for treatment of compulsive behaviours in dogs at a dose of 0.3mg/kg to 0.5mg/kg twice daily, rather than for analgesia.

Other authors have suggested similar dosing for chronic pain, starting at the lowest dose and increasing gradually. Side effects can include increased urination and cognitive dysfunction in older dogs.

Antiepileptic drug options are as follows:

Gabapentin has gained popularity in use for chronic pain over the past few years. However, although it appears to be very useful in the clinical setting, few studies have been conducted into its efficacy for chronic pain. Much of the published work has been associated with postoperative pain, where it has not been shown to be very effective. This may be, in part, due to the dosing schedule in some papers – for example, 10mg/kg twice a day in the paper by Aghighi et al (2012).

Gabapentin appears to be rapidly absorbed and eliminated (Kukanich and Cohen, 2011), which would indicate it requires frequent dosing. One study that did investigate its use in a chronic pain setting looked at the QoL and pain scores in patients with Chiari-like malformation and syringomyelia (Plessas et al, 2015). In this study, gabapentin was compared to topiramate (an antiepileptic medication) and assessed for improvement in QoL when added to treatment with carprofen. Gabapentin appeared to improve QoL compared to carprofen; no significant difference was seen between gabapentin and topiramate.

Pregabalin is a similar molecule to gabapentin, but appears to have greater bioavailability when administered orally. Salazar et al (2009) found 4mg/kg administered to dogs appeared to result in blood levels similar to those that produced analgesia in humans. Again, further studies are needed to establish efficacy.

Ongoing studies are using this drug to treat neuropathic pain associated with Chiari-like malformation and syringomyelia. One factor that may preclude its use in veterinary practice is price, as it is significantly more expensive than gabapentin.

Derived from chilli peppers, capsaicin has been used to treat post-herpetic neuralgia in the form of a cream or a plaster. The higher percentage patch (8%) was more effective than the low concentration when used for this purpose (Moore, 2010), but was only recommended as a second-line treatment in the findings of the meta-analysis.

Application to patients is limited at the moment due to the form the drug is delivered in. A US clinical trial is being conducted looking at intra-articular injection of this molecule, but it appears to be early in the research.

Several mechanisms exist by which tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) produce analgesia, including antagonism of NMDA receptors. In addition to gabapentin and pregabalin, this drug group is considered first-line treatment in humans for neuropathic pain. Amitriptyline is the most common in this group used for analgesia.

No clinical trials evaluate the use of these drugs in chronic pain, but it seems likely the action is similar to that in humans. A pharmacokinetic study has suggested a dose of 3mg/kg to 4mg/kg every 12 hours would achieve adequate levels to produce analgesia.

Opioids have been increasingly used to treat chronic pain in veterinary species, mirroring its use in humans.

As the action of this drug at opioid receptors is weak, a significant part of the analgesic action is of non-opioid origin. The bioavailability appears to be high in both the cat and dog. Clearance appears to be more rapid in the dog compared to humans, meaning frequent dosing, such as three times daily, may be required.

A large variety of doses have been quoted in the literature, which may be due to the different analgesic requirements of conditions and the rest of the analgesic protocol being used. It is also unclear how useful it is for long-term management of chronic pain. Side effects include vomiting, diarrhoea, sedation, dullness and dysphoria. The possibility also exists of an interaction between TCAs, serotonin reuptake inhibitors and monoamine oxidase inhibitors, which can result in seizures.

Tapentadol is similar to the M1 metabolite of tramadol, so it does not require metabolism for activation. Two studies looked at pharmacokinetics in dogs, but both used IV administration rather than oral, the more usual route of administration when drugs are used for chronic pain. It did appear to result in more reliable blood levels than tramadol, so may be of interest if a patient is not responding to treatment with tramadol or those suffering from severe side effects.

A large body of evidence exists that once chronic pain has been established, the disease process will not be worsened by it, and exercise and physical therapies will help improve QoL. The exercise programme can be combined with weight control to reduce the load on joints.

Tailoring exercise to the general physical abilities is, of course, important and will tend to reduce the incidence of detrimental side effects. This will have an additional effect of helping to improve the pet-owner bond, which may, in turn, improve the owner’s ability to detect and assess discomfort in their pets. This type of exercise would include physiotherapy and hydrotherapy.

As with more conventional pain and disease treatments, it is important a full clinical exam and working diagnosis is established before embarking on adjunctive therapies.

Acupuncture can be defined as the insertion of a solid needle into the body with the purpose of therapy, disease prevention or maintenance of health (Acupuncture Regulatory Working Group, 2003). In the UK, acupuncture is an act of veterinary surgery. The mechanism of action of acupuncture is not fully understood, but an intact nervous system is a requirement for it to work. It appears some effects are mediated by endorphins and other opiates (opiate antagonists, such as naloxone, can block the effect of acupuncture).

Evidence also exists that acupuncture up regulates messenger ribonucleic acid for pre-encephalin; this is likely to be the mechanism of the increasingly prolonged effects of acupuncture over time. The placement of needles stimulates Aδ fibres, which are associated with acute pain. This means the onward transmission from C-fibres is suppressed so chronic pain decreases. This is most effective when the needle is placed near the source of the pain.

The evidence for effectiveness is variable. Few controlled studies have been conducted assessing the effects in veterinary patients. One study in the Canadian Veterinary Journal (Lane and Hill, 2016) showed some short-term improvement in comfort and mobility after combined acupuncture and manual therapy. However, other studies have not shown a beneficial effect compared to other treatments.

Acupuncture can be difficult to assess in a blinded study because of the nature of the intervention. Other effects of acupuncture are anxiolysis, improved healing and anti-nausea. Treatment will usually be initiated one to three times a week for three to four weeks. After this, the treatment interval can be increased, but the final treatment interval is patient dependent. The majority of treatments will be performed on conscious patients, but can be carried out under sedation if a clinical indication exists.

Electroacupuncture involves passing a low electric current through paired acupuncture needles. The stimulation is more intense and the effects are potentially longer lasting.

Some acupuncturists use this as their default acupuncture technique, but others use it when patients are not responding for as long as expected with the usual dry needling technique. It produces a more intense stimulation and the treatments can usually be shorter.

With this type of treatment having been used to treat tendon and ligament injuries in humans, extracorporeal shock wave therapy involves the use of high-pressure sound waves emitted at a high velocity. It can be applied in two ways:

The effects are thought to include:

The evidence for effectiveness is weak and conflicting in the dog.

Mesenchymal stem cell therapy is a popular area of research in both human and veterinary treatment of arthritis. The basic premise is to harvest mesenchymal stem cells (often harvested from fat cells), which are treated before being injected into arthritic joints. The theory behind their use is the growth factors and cytokines they produce may stimulate recovery and reduce inflammation.

Some studies have investigated the addition of bioactive carriers – for example, platelet-rich plasma. Platelets are thought to supply a broad spectrum of compounds – for example, growth factors, which may help to improve the effect of MSCs.

Bench top research success has not been translated into clinical success as yet; however, it is an area in which a greater amount of research is warranted.

Some patients may benefit from attendance at specific pain clinics. These will usually involve a holistic approach to each patient’s pain. These consultations will often be longer, as a detailed history needs to be taken, including the issues the owners perceive to be important. It is useful to make some objectives that can be agreed on by the owner and clinician.

At these appointments, the medication can be reviewed, as well as changes to the pet’s environment, which may improve the condition. Sometimes, withdrawal of treatment in a controlled manner may be necessary to ascertain efficacy of treatment. It may be more likely for owners to distinguish a deterioration rather than an improvement. This should only be undertaken after consultation, and education of the pet owner and a plan for rescue analgesia should be in place.

Chronic pain is multi-faceted and often difficult to treat. Where possible, the initiating cause should be treated, but, equally, this may never be identified. A close working relationship with the pet owner is vitally important for success.

Many treatments – both pharmacological and non-pharmacological – still require further studies to show if they have a truly beneficial effect. However, it must be kept in mind the variation in disease process and pain experienced is very variable between patients, necessitating individual treatment plans.