19 Mar 2018

Ian Wright discusses possible changes to the Pet Travel Scheme following Brexit.

Since the Pet Travel Scheme (PETS) was relaxed in 2012, pet travel has increased year-on-year, from 140,00 dogs travelling from the UK in 2012 to 164,800 in 2015.

These figures reflect an appetite for owners to travel with their pets, as seen in practices up and down the country.

Easier movement of pets, with less paperwork, has enabled owners to take their cats, dogs and ferrets with them on holidays, to second homes overseas and to see family living abroad. However, this increase in pet travel has occurred at a time of increased human migration, pet movement and climate change – providing favourable conditions for the rapid spread of parasites and their vectors. This has increased the risk of pets and their owners encountering exotic parasites while abroad, and their introduction to the UK through travelled dogs and cats.

Regulation of pet movement must, therefore, strike a balance between making pet travel as stress free as possible, while preventing the spread of parasites detrimental to health.

The combination of Brexit and the arrival of a variety of exotic ticks and tick-borne diseases, such as Rhipicephalus sanguineus and babesiosis, has led to many in the veterinary profession seeing both an opportunity and a necessity to add more parasite control regulation to PETS. The scheme exists, however, to limit the spread of zoonotic parasites and vectors, and not to prevent parasite spread associated purely with companion animal health. Therefore, for any change to be implemented it must:

If these four criteria can be met, lobbying and subsequent negotiations may succeed.

Within the framework of this criteria, what are the requirements, what must change, what might we lose and what changes should the veterinary profession lobby for?

EU pet travel regulations for the non-commercial movement of dogs, cats and ferrets travelling within EU and listed non-EU countries require pets to:

Dogs entering the UK, Ireland, Finland, Norway or Malta must be treated for tapeworms by a vet with a product containing praziquantel (or equivalent) no less than 24 hours and no more than 120 hours (between 1 and 5 days) before its arrival in the UK.

Pets travelling from unlisted non-EU countries must conform to the same rules, but, in addition, after rabies vaccination, a blood serology test must be taken, followed by a three-month wait before entry into the UK. Unlisted countries can be found on www.gov.uk

These requirements allow identification and movement of pets on traceable routes to reduce smuggling and other illegal pet movement.

Raising the minimum travel age for pets has also helped reduce smuggling, as puppies are in highest demand as new pets. Rabies vaccination and the compulsory tapeworm treatment reduce the risk of rabies and Echinococcus multilocularis spreading.

Despite suggestions by Michel Barnier if Brexit negotiations fail it will make it harder to travel with pets from the UK to the EU (www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-41969672), no statutory changes have to take place.

The UK can remain a non-EU listed country on the scheme and the requirements stand unchanged, as is the case for Norway. However, the scheme will form part of the negotiation process and is up for consultation. So a better time has never been available for comprehensive changes to the scheme to be made.

Lobbying is, therefore, vital, not only for potentially adding changes that would make a significant impact on disease spread, but also to protect the existing regulations.

The reduction of pet smuggling and illegal pet movement is of benefit to governments across Europe, for biosecurity, animal welfare and economic impacts. Measures countering fraud and illegal movement are, therefore, unlikely to be relaxed. This view is reinforced by changes to PETS in 2012 and 2014.

Changes in 2012 relaxed rules in place to restrict pathogen spread. These included removal of compulsory rabies blood testing for EU and non-EU listed countries, removal of the compulsory tick treatment and increasing the window in which the compulsory tapeworm treatment can occur.

In comparison, the changes to the scheme in 2014 heightened security, with tamper-resistant and less easy to forge passports, and an increase in the minimum rabies vaccination age on the scheme. This demonstrates where EU legislation priorities lie and makes potential changes regarding infectious disease of greatest concern.

In Europe, the development of an oral rabies vaccine and mass dosing of the fox population has dramatically reduced the numbers of foxes infected, and centres of infection in the fox population are limited to areas in eastern Europe. However, the reservoirs in eastern Europe remain and sporadic outbreaks of fox rabies have occurred in southern European countries, such as Greece and Italy. As a result, compulsory rabies vaccination for travelling pets continues to play a significant role in preventing re-entry of rabies into western Europe and, therefore, further relaxation around rabies vaccination rules under PETS is unlikely.

In contrast, compulsory tapeworm treatment is under constant pressure to be further relaxed or removed. E multilocularis, the tapeworm the treatment is in place to prevent, is a severe zoonosis listed on the World Health Organization’s 17 most neglected diseases.

The adult tapeworm is carried by both foxes and dogs, with foxes acting as a reservoir of infection and microtine voles as intermediate hosts. Dogs and foxes become infected by predation of these voles, with infection in dogs bringing the parasite into close proximity to people.

Cats can act as definitive hosts for E multilocularis, but have a lower worm burden, with lower fecundity than canids.

Zoonotic infection occurs through ingestion of eggs passed in the faeces of dogs and foxes, which are immediately infective. This can occur though association with infected dogs, contamination of public spaces through dog fouling, or eating contaminated fruit and vegetables intended for raw consumption. Zoonotic infection results in local and metastatic spread of cysts, leading to hepatopathy and potential multiple organ involvement. Despite significant advances in treatment over the past two decades, infected individuals can still expect a significant reduction in life expectancy.

Although E multilocularis is not endemic in the UK, the increase in pet travel across UK borders, the relaxation in the time period allowed between tapeworm treatment and return to the UK, and the parasite spread across Europe potentially threaten this status.

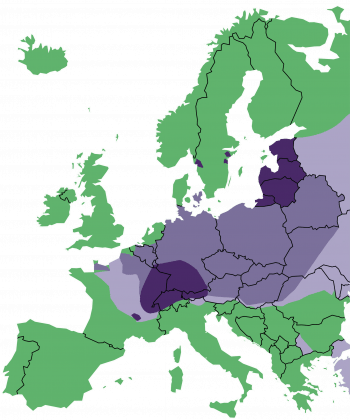

E multilocularis has spread west and north through Europe and has become established in the Jutland peninsula of Denmark, Sweden and the north-west coast of France (Figure 1). Only the UK, Ireland, Malta, Finland and Norway have endemic-free status in Europe. This wide spread endemicity and the limited surveillance taking place in Scandinavia has led to the benefit of the compulsory treatment being questioned. This, in turn, led to the proposal to remove it being tabled in 2012 and, ultimately, only effective lobbying from the veterinary profession led to it being kept, albeit with an increased treatment window.

PETS requires dogs to be treated with praziquantel between one and five days before entry into the UK. This simple treatment has prevented endemic foci from developing, and remains vital. It has been demonstrated that if this compulsory treatment is abandoned altogether, it is almost inevitable E multilocularis will be introduced into the UK.

For every 10,000 dogs travelling on a short visit to an endemic country, such as Germany, the probability of at least 1 returning with the parasite is approximately 98%. This probability increases to more than 99% if dogs have been longer-term residents (Torgerson and Craig, 2009). Although the treatment rules allow a window of opportunity for infection, it has so far been sufficient to prevent the parasite being introduced.

If E multilocularis is allowed entry into the UK, the large fox and microtine vole population will make prevention of E multilocularis becoming endemic difficult, if not impossible, to achieve. It is, therefore, vital the opportunity for the parasite to gain entry to the UK is kept to a minimum. If the scheme is renegotiated as part of Brexit, further pressure to remove this treatment will occur, so the UK veterinary profession and its representative body must be prepared to lobby and campaign to keep it once more.

Although a wide range of changes to PETS have been suggested – from scrapping the scheme to further relaxation of the rules – three suggestions have been made that would tighten the rules further and be lobbied for post-Brexit.

The four-month minimum travel age (3 weeks after vaccination at 12 weeks) was added to the scheme in 2014 as a result of increased puppy smuggling, and associated disease spread and welfare concerns. These practices were highlighted by Dogs Trust, which has, subsequently, suggested six months may be a more effective minimum age to have an impact on smuggling. This is because puppies masquerading as a six-month-old dog would be easier to spot by veterinary health professionals than four months as they will have matured further, with adult dentition.

Although no statistical evidence exists of this being the case, it has clear logic underpinning it and would further a policy that has already been partially adopted. Assessments would have to be made on the impact of charities, such as Guide Dogs, that move young dogs across international borders for breeding and supply purposes, but, in principle, is a change that could be lobbied for, with the potential for reduced illegal activity, increased welfare and reduced parasitic disease spread as a result.

Since compulsory tick treatment has been dropped, a number of exotic ticks have been brought into the UK on travelled dogs, and outbreaks of babesiosis have occurred in the south-east of England.

The presence of Dermacentor reticulatus ticks in the UK in west Wales, Devon, Essex and London present, an opportunity for Babesia canis to become endemic if introduced through travelling dogs returning from abroad.

Since the establishment of Public Health England’s (PHE) Tick Surveillance Scheme (TSS) in 2005, 27 records of D reticulatus exist that have not been associated with overseas travel. Seven of these records were submitted during 2016, which represents the highest number of records received in a single year to date (Medlock et al, 2017).

This combination of factors has led to an endemic foci of B canis infection establishing in Harlow, Essex, with B canis being confirmed in local Dermacentor ticks and untravelled dogs (Phipps et al, 2016; Woodmansey, 2016). Further untravelled cases were confirmed in Romford in 2016 and Ware in 2017 (Woodmansey, 2017).

Records of the exotic tick R sanguineus received by the TSS are also increasing each year and, in the past two years, two confirmed house infestations have occurred in the UK (Hansford et al, 2017). A Hyalomma lusitanicum tick was also found on a dog in the UK that had returned from Portugal. This species of tick is a potential vector of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus, which is highly pathogenic to people (Hansford et al, 2016).

These increases in exotic ticks on UK shores have been widely blamed on the dropping of the compulsory tick treatment by large sections of the veterinary profession. While it is difficult to quantify what impact dropping the treatment had, reintroducing it would raise awareness among clients and ensure tick prevention was discussed when pet passports are issued. Care must be taken in relying on legislation to solve the exotic tick problem in the UK. No tick preventive product is 100% effective and, on treated dogs, some ticks may, and over time will, survive.

Pets will also be exposed to tick-borne disease abroad if only a compulsory treatment is relied on. A compulsory treatment will, therefore, only be effective if combined with treatment before, during and after travel, and if pets are checked for ticks abroad and on return to the UK.

A number of obstacles in getting the compulsory tick treatment reintroduced exist:

The compulsory tick treatment should, therefore, be viewed as a useful tool in a overall UK tick prevention strategy, but one likely to be very difficult to obtain. If a zoonotic disease risk argument is to be made to obtain it, tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) is the best option and represents a genuine health risk to the UK population.

TBE is a virus transmitted primarily by Ixodes ricinus ticks. It is a potentially severe zoonosis, with infections most commonly resulting in a transient fever, but sometimes progressing to meningoencephalitis and CNS signs. Although human infection is uncommon, with 1 case per 10,000 hours spent in woodland activity, it can be fatal, so concern about its spread through Europe has been high.

In Europe, it is a parasite predominantly of eastern Europe, but it has been moving north and west in its distribution, with cases beginning to emerge in central and northern Europe (Pettersson et al, 2014).

I ricinus is endemic in the UK, so infected ticks or pets entering the country could lead to establishment of infection in native ticks.

The half-life of praziquantel is approximately four to six hours, so infection with E multilocularis may occur in the five-day window between compulsory treatment and entry into the UK. The epidemiological logic of reducing this treatment window to 48 or 24 hours is clear.

The increase to five days, however, has allowed owners travelling with their pets far greater flexibility in choosing where and when to have the treatment administered. The regime has also kept the UK, Ireland and Malta free of infection so far, and the five-day window represents a relatively small risk compared with the large land borders Norway and Finland have with endemic countries. This means it is unlikely the treatment window will be reduced, so rather than lobbying for this, efforts should focus on keeping the current requirement and encouraging owners to treat all travelled dogs with praziquantel within 30 days after entry into the UK.

Brexit represents an opportunity to review PETS, particularly in the light of increased spread of parasites and vectors, not only into the UK, but across the whole of Europe.

Within the consultation, an opportunity exists to lobby MPs and Government officials to negotiate for additional requirements to be added to the scheme. In deciding what changes to lobby for, the advantages and disadvantages must be carefully considered, and, whatever legislation is adopted, it will only be successful if combined with effective parasite control planning and client education.

The tapeworm treatment remains crucial, however, and although the Government will rightly negotiate to maintain PETS post-Brexit, it should not be at any cost.