12 Dec 2016

Nigel Dougherty revisits lessons learned and options considered from a dog that presented following a vehicle-induced injury.

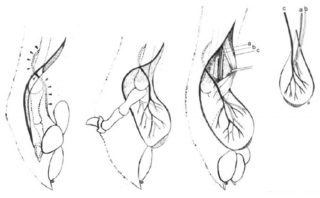

Figure 2. The technique for the phalangeal filleting of the fifth digit to allow the transposition of its pad to the metacarpal pad defect area. Images: Fowler, 2006.

An adolescent New Zealand heading dog, a working breed, was presented to the author following vehicle-induced shear stress to the manus, manifesting as a contaminated crush avulsion injury involving the width span of a metacarpal pad.

The avulsion involved full thickness of the panniculus adiposus and associated tractus tori avulsion (Figure 1), leaving it attached distally by a bridge (2.5cm width, 1cm thickness). Notwithstanding concurrent bruising of the manus, neither orthopaedic nor systemic compromise were evident. Following attempts to salvage the pad (Figure 1), it eventually became ischaemic.

Given the vital functional importance of the pad, the foreleg was amputated because the author was not aware of reconstructive alternatives. Retrospectively, function of the forelimb could have been salvaged through documented pad preservation or reconstruction techniques and the author thought it would be informative to research and present such options and their appropriateness in this case, for the benefit of those faced with a similar presentation in future.

Immediate wound considerations included the following.

A prerequisite for reconstruction, addressing contamination was performed by lavage (0.9 per cent saline per 20ml syringe, 18G needle). Crush injuries usually demand some open wound management (Fowler, 2006) for debridement, although this avulsion was resutured in position, generating difficulties both for establishing adequate dependent drainage and performing staged debridement of the avulsion bed.

Knowledge of ischaemic injury to the avulsed section, whose viability was difficult to immediately determine. Full extent of resultant necrosis usually manifests from five to seven days since injury (Fowler, 2006), potentially taking longer depending on the ischaemic nature (Bray, 2016). Clinical assessments at presentation were not considered predictive of avulsion viability.

After five days, the avulsion demonstrated non-viability, being cold to touch and with absence of induced bleeding on any cut surface. Severance or crushing injury was responsible, likely involving all four branches from the superficial palmar arterial and venous arches, as well as supply from the deep palmar arterial and venous arches that give rise to the palmar metacarpal arteries and nerves (Budras et al, 1996).

Successful preservation of limb function would require restoration of specialised pad tissue over the palmar metacarpal area for weight bearing, given its importance in withstanding compression and abrasion.

This case demanded recruitment of such tissue from elsewhere for successful reconstruction of the weight-bearing surface. Tissue incorporated would need to demonstrate capability for hypertrophy and keratinisation, to withstanding the abrasive effects of ground contact.

Sufficient pressure dissipation would prevent ischaemia over metacarpal prominences (Basher et al, 1990) and some authors consider intact sensation of transposed pad tissue as a prerequisite for the prevention of trophic ulcer development (Basher et al, 1990; 1991).

Given these considerations, options for restoring limb functionality are retrospectively considered in descending order of preference, as alternatives to the limb amputation that

was undertaken.

Pedicle flap elevation and transposition of the second or fifth digital pad, or both, from the affected foot (Swaim and Garrett, 1985; Fowler, 2006) to the site underlying the former metacarpal pad (Figure 2).

This transposable length is achieved by phalangeal disarticulation and filleting of the chosen phalanx at the level of the metacarpophalangeal joint, excluding periosteum for its unwanted osteogenic potential and ensuring venous, arterial and neurological supplies are preserved. This technique would have been the reconstructive technique of choice for this patient, conferring the following advantages:

In common with the following options, morbidity may arise through inherent failure of the technique to address the mobility of transposed tissue, given the loss of connective tissue anchor to the metacarpal bones.

Microneurovascular free pad flap (Basher et al, 1990; 1991) would also have permitted transfer of specialised subdermal tissue and would introduce the capacity for sensation in the area of metacarpal pad replacement. It offers the same benefits as the aforementioned pedicle flap elevation and would have been the technique of choice if ischaemic compromise had developed in the distal digits of the affected paw.

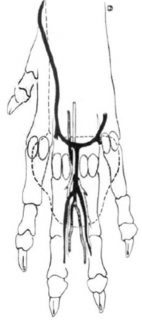

In this technique, a neurovascular axial pattern combination digital pad and skin flap is established, ideally from the fifth digit of the hindlimb, elevating and severing the neurovascular bundle consisting of the deep plantar metatarsal artery IV (feeding the plantar common digital artery IV), the superficial dorsal metatarsal vein IV and the deep plantar metatarsal nerve IV, latterly to offer partial sensation to the pad (Figure 3).

This donor bundle is anastomosed with recipients consisting of a superficial palmar metacarpal artery, the cephalic vein and a superficial palmar metacarpal nerve (Figure 4).

Given the shear stresses involved in this particular patient’s injury, difficulties were anticipated in recruiting healthy recipient vessels following likely damage to superficial palmar metacarpal arterial and venous arches – even though, in one instance, recipient vessels were identified after prolonged preparation of a healthy granulation bed where metacarpal pad had been experimentally incised and removed (Basher et al, 1991).

With regards to pad grafting of the avulsed metacarpal pad, immediate preservation of the dermal layer of the avulsed metacarpal pad could have been achieved by its preparation and placement into a temporary recipient bed of cutaneous trunci muscle.

Elevation of the associated recipient bed into a bipedicle flap could then allow its incorporation on to the prepared bed of the original wound site by a two-staged severance of the bipedicle flap (Pavletic, 2010).

This technique does not permit the aforementioned considerations to be met, but would have been a management option if the digits or digital pads were compromised on the same foot.

Multiple, full-thickness, paw pad seed grafts, involving excision of SC paw pad cushion from the deep surface of healthy pad(s) to the level of the deep surface of the dermis (Figure 5).

These are placed circumferentially within incisions made into healthily granulated recipient bed (Swaim et al, 1993). Graft stratum corneum will slough, but should regenerate over several weeks, but the major disadvantage remains this approach does not permit transfer of the specialised SC paw pad cushion with the graft (Fowler, 2006).

In common with other techniques, further canid-specific research is required to assess the importance of the proposed requirement to restore intact sensation.