3 Oct 2023

Jack Reece discusses the likelihood of the disease being seen more frequently in this country among imported dogs.

Image © Михаил Решетников / Adobe Stock

A Great and quite proper anxiety exists over the number of dogs – particularly pups – imported from the farther reaches of Europe and elsewhere.

Not only do these imports pose problems for the welfare of the animals concerned, but they also risk the importation of diseases currently unknown or rare in these islands. Recent concerns have been about brucellosis, rabies and echinococcosis, and also about parasites such as Rhipicephalus sanguineus and associated diseases.

Distemper is a disease that has largely been eradicated from the country through comprehensive vaccination of dogs and elimination of strays. It is, however, endemic in many countries that have large free-roaming dog populations. Distemper is also a disease seen most commonly in puppies and young dogs.

It seems likely, therefore, that cases of distemper are likely to be seen more frequently among imported dogs from eastern Europe and elsewhere.

Distemper has been recognised in the UK since at least the mid-18th century1. The causative virus, a morbillivirus, was first identified in France in 1905 and confirmed by Patrick Laidlaw at the Medical Research Council in 1926, who devised the first immunisation to the disease, research for which he was awarded the Royal Society’s Royal Medal. Routine regular vaccination of dogs has made diagnoses of distemper very rare in the UK in recent times. Distemper is mainly a disease of young dogs, under a year of age. An African study reported only 9.2% of cases were in dogs older than one year of age2.

This may be explained by the virus predilection for rapidly dividing tissues; by the reported 80% fatality rate, with which the author’s clinical experience in India would concur or even consider an under-estimate, and by the fact that between 38% and 48% of adult Indian street dogs were found to have protective immunity through field exposure3.

Distemper virus enters the body by inhalation and causes a biphasic pyrexia, the first phase of which may be missed. The incubation period is typically one to two weeks, but may be more than a month. The disease causes mucopurulent ocular and nasal discharges (Figure 1).

Eyes may have conjunctivitis. Considerable build-up of inspissated discharge around the eyes, on the eyelids (Figure 2) and around the nose is often reported. Progression to severe respiratory disease including pneumonia is common. The alimentary tract may be affected with symptoms from mild diarrhoea and vomiting to severe persistent bloody diarrhoea, with anorexia and weight loss.

Concurrent with these signs may be neurological signs, or these may develop later if the animal survives the diarrhoea and pneumonia. These signs may include changes in temperament, chorea, which can often be pronounced, paralysis and seizures.

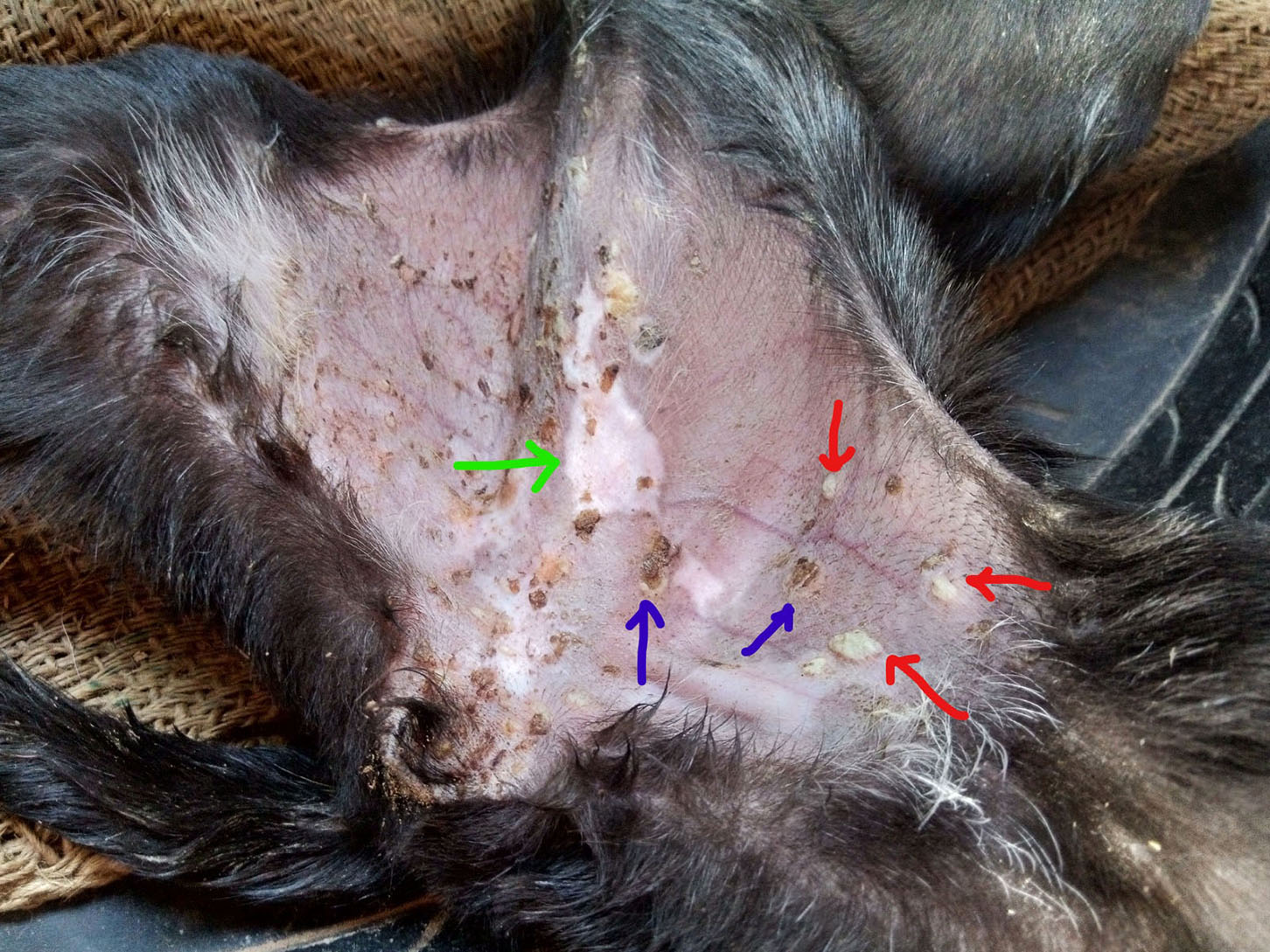

As the virus attacks the cells that produce tooth enamel, puppies infected during the development of the permanent dentition may have damage and discolouration of the dental enamel (Figure 3), which may lead to dental disease and injury as the animal ages. Maduike Chiehiura Onwubiko Ezeibe states that 95% of animals with distemper have white pustules on the hairless areas of the caudal ventral abdomen.

The author would agree with this observation – particularly in puppies under about six months of age, where such white pustules are almost pathognomonic for distemper (Figure 4). These are usually around 5mm in diameter, but commonly coalesce into large, more irregular pus filled blisters. As each pustule bursts, it leaves a ragged scar.

Some animals with distemper show all of the previously mentioned pathologies, some only some of them. In the author’s experiences from India, where distemper is the biggest single infectious cause of death among free-roaming young dogs, animals generally first present with ocular and upper respiratory tract symptoms and lassitude. These symptoms progress over a few days to more severe respiratory disease, an increase in mucopurulent ocular and nasal discharges and anorexia.

Diarrhoea then follows, along with neurological signs and emaciation, which can become pronounced. Progression may be rapid – within a few days – or take a few weeks. Death is common.

Laboratory diagnosis of distemper infection, if deemed necessary, can be achieved through distemper virus real-time PCR tests on discharges and blood identifying viral antigen, and by serum ELISA test confirming the presence of antibodies. Both are available commercially as kits.

Differential diagnoses for distemper are many, including, for example, parvovirus infection and kennel cough. However, none of these differential diagnoses combine together to give respiratory, alimentary, skin and neurological signs in the way distemper does. Neurological distemper with its change in temperament, ataxia and progressive paralysis may present very similar to canine rabies.

As a viral disease, treatment is largely symptomatic and largely unsuccessful. Good nursing is essential. In an American animal shelter setting, the death rate in a distemper outbreak with only a few (25) cases was reported to be around one-third, a result attributed to “proper supportive care”4.

If treatment is successful, the animal is likely to have residual neurological sequelae such as chorea, which may last years or indeed be permanent. Distemper chorea does, however, appear to improve slowly with long-term good care and nutrition with twitching reducing in severity.

Dogs that recover from distemper often seem to have “weak” chests or guts, prone to other future infections.

Classically, hard-pad, hyperkeratosis of the foot pads and hairless nasal planum, is considered a cardinal sign of canine distemper infection. Indeed, the disease was commonly called “hard-pad” in the UK.

However, in the author’s experience and in that of Ezeibe in Nigeria, hard-pad is rare among clinical cases (less than 3% in the Nigerian study).

Distemper is transmitted by aerosol and in kennel settings through the use of communal drinking and feeding bowls, and the exposure of animals to the discharges of infected animals; transplacental infection can also occur. Some infected animals can shed the virus for many months, even apparently after respiratory and GI tract signs have resolved. As an enveloped RNA virus distemper does not persist in the environment for long – only a few hours – although cool, damp conditions aid viral survival.

The virus is destroyed by most readily available disinfectants. In kennels and shelters, treatment and control are best achieved by isolation of cases, barrier nursing and disinfection. Prevention of infection is by vaccination. Many vaccines and vaccine schedules are available; these are beyond the scope of this article.

Canine distemper virus is infectious to some other domestic mammals, including ferrets, in which infection is reported to be serious. Ferrets may be successfully vaccinated against distemper. Canine distemper has been responsible for deaths in lions (Panthera leo leo) in the Serengeti and also Asiatic lions (Panthera leo persica) in Gujarat, India. The virus causes severe infectious disease in many wild carnivores, including leopards and tigers.

Because of the close association between many of these wild predators and free roaming dog populations in Africa and Asia (dogs are the favoured prey of leopards in India, for example), canine distemper from free-roaming dog populations poses a real threat to the conservation of these major carnivores. Distemper virus is not zoonotic.