5 Aug 2019

Victoria Robinson, using case examples, looks at treatment and management of this chronic problem, including owner advice.

“Not another article on canine atopic dermatitis” (CAD), I hear you mutter into your coffee on your lunch break. Okay, so the second part of that sentence may be a rarity; however, CAD is a common chronic problem in general practice and one that often leads to a lot of frustration.

It is a complex, multifactorial disease and long-term management options are hard to discuss in a regular 10-minute appointment slot1.

The aim of this article is to briefly discuss the pathogenesis, clinical signs and work-up required to reach a diagnosis of CAD. The focus will be on treatment options, with case-based examples designed to help with common cases encountered in general practice.

CAD is defined as genetically predisposed inflammatory and pruritic skin disease associated with the production of IgE antibodies, usually to environmental allergens2. Pathogenesis is multifactorial, complicated and incompletely understood.

The disease develops as a result of a complex interplay between genetics, defects in skin barrier function, and aberrant responses of the adaptive and innate immune systems. This results in allergic sensitisation, alterations of the skin microbiome and secondary infection.

Suggested risk factors for development of CAD include having a parent(s) with CAD, living in an urban environment, increased average rainfall, feeding a non-commercial diet and regular bathing3-6.

Protective factors include living with other pets, woodland exposure and rural life6. Canine adverse food reaction involves either immune or non-immunological reaction to foods, which can result in development of clinical signs indistinguishable from atopic dermatitis.

Dogs will typically start to show clinical signs between six months and five years of age. Pruritus is the primary clinical sign, and frequently involves ears, periorbital skin, muzzle, axillae, flexural surfaces, ventral abdomen and perineum.

Key breed differences exist, such as French bulldogs showing extreme facial pruritus, West Highland white terriers developing dorsal pruritus and German shepherd dogs with ventral abdominal pruritus7.

CAD remains a diagnosis of exclusion by ruling out all possible diseases that may mimic clinical signs, including infections (bacterial +/- fungal), ectoparasites and food.

Cytology, skin scrapes, hair plucks and food trial using a novel protein or hydrolysed diet exclusively, for patients affected year-round, are all part of the standard work-up.

Favrot’s criteria (Panel 1) can be used to help with diagnosis of CAD8. If a patient has five of the criteria then sensitivity is 77%, specificity is 83%; with six criteria sensitivity is 42% and specificity is 94%.

Care should be taken with interpretation and it is important to bear in mind this is a diagnosis made after the exclusion of other pruritic skin diseases.

Readers are directed to the many excellent articles on diagnosis of atopic dermatitis, including Hensel et al (2015)9.

Management of a dog with atopic dermatitis is challenging; I should know – I own an affected rescued French bulldog. It is important to bear in mind management is always multimodal. For example, my dog is on multiple medications, including regular topical treatment. Remembering to do her medication regime at the end of a busy day is sometimes the last thing I feel like doing; however, I understand the consequences of not carrying this out.

Compliance relies on understanding and willingness to follow a treatment plan, and adherence is the extent to which the treatment plan is followed. Only a few studies looking at compliance in veterinary medicine exist, with none looking at polypharmacy, which is quite often the management regime for atopic patients10.

Communication with clients about the pathogenesis, long-term treatment and consequences of not managing disease is key to a successful outcome. Trying to discuss management options with clients in a 10-minute consultation is unlikely to be satisfactory for either party. Where possible, try to book clients in for a longer appointment and charge appropriately for your time. Handouts can reinforce the discussion and give owners reliable information.

Veterinary nurses are a valuable part of the team, and their training and experience can be invaluable in the management of CAD patients. Owners may confide more in nurses than vets for various reasons and the use of nurse clinics can aid compliance11.

Additional dermatology training is available with the BSAVA Vet Nurse Merit Award.

Poor compliance can be the result of:

Compliance can be improved by:

Treatment of CAD can be broadly divided into:

To date, ASIT remains the only treatment that moderates the immune response to allergens, although the full mechanism of action is yet to be eluded.

ASIT relies on the identification of disease-relevant allergens using intradermal or serological testing. Clinical signs and history are pertinent to allergen selection – if a patient shows sensitisations to grass pollen, but has year-long clinical signs, the test employed is not identifying the whole picture.

Furthermore, patients with year-long clinical signs should be assessed for adverse food reaction as aforementioned. Serology for food-specific IgE/lgG is unreliable and should not be used for the diagnosis of food allergies.

ASIT can be administered by injection or sublingually, with clinical efficacy comparable between the two treatments at around 60% to 70%12-13.

Patients often present with secondary infection (bacterial/fungal or mixed) that can cause variable pruritus that may be intense in patients that have developed microbial hypersensitivity.

Treatment of the secondary infection is imperative to determine the baseline pruritus level. Furthermore, antipruritic treatments are often not very effective in the face of active infections. Cytology should be used to determine what the offending microbial infection is and to select the appropriate treatment.

Cytology should also be used to ensure clinical resolution of infection before starting antipruritic/anti-inflammatory treatment.

Ectoparasite infestations should be ruled out as part of diagnostic work-up in newly presented pruritic patients, or CAD patients that have flared. Skin scrapes, hair plucks, acetate tape and coat brushing can be used to determine the presence of mites, lice and fleas, respectively.

Long-term preventive treatment should be used year-round for both affected and in-contact animals. A plethora of prophylactics are available, and the choice of product should take the client and pet’s lifestyle into consideration. For example, certain spot-on and collar treatments will have reduced efficacy in patients that are regularly shampooed or swim.

This is a mainstay of management of human patients with atopic dermatitis; however, in general, our patients tend to be hairier and so application of barrier creams is rarely practical.

Barrier function can be improved with diets containing omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, as well as use of topical spot-on products to help normalise the lipid balance and organisation of the stratum corneum.

Veterinary shampoos containing lipids and complex sugar or phytosphingosines, raspberry oil and lipids have been shown to have a modest effect on reducing pruritus and clinical lesions, and can be considered as a useful adjunct18.

CAD is a lifelong disease that requires long-term management to prevent inflammation, itch and secondary infections. Each patient and owner is different, and treatment plans need to be tailored to their specific needs. Furthermore, management requirements may vary seasonally or alter as the dog gets older.

Communication and compliance is key between the veterinary team and the client for a successful outcome.

The practice of dermatology can be very rewarding, and you can make a huge difference to the pet and owner’s quality of life.

A four-year-old male neutered bichon frise with a four-month history of recurrent moderate aural, axilla and pedal pruritus. No routine ectoparasite control.

Clinical exam: Mild saliva staining on the palmar/plantar aspects of all four paws. Mild ceruminous discharge in the vertical canal of both ears.

Differentials: Ectoparasites (Otodectes cynotis, Trombicula autumnalis); infections (bacterial +/- fungal); atopic dermatitis (environment +/- food).

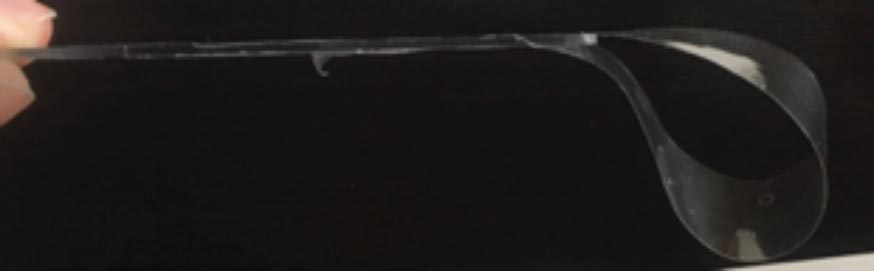

Diagnostics: Acetate tape cytology of the axillae, dorsal and palmar surfaces of the paws. Acetate tape of the dorsal surfaces of the paws for check for T autumnalis. Cytology of otic discharge using a cotton bud.

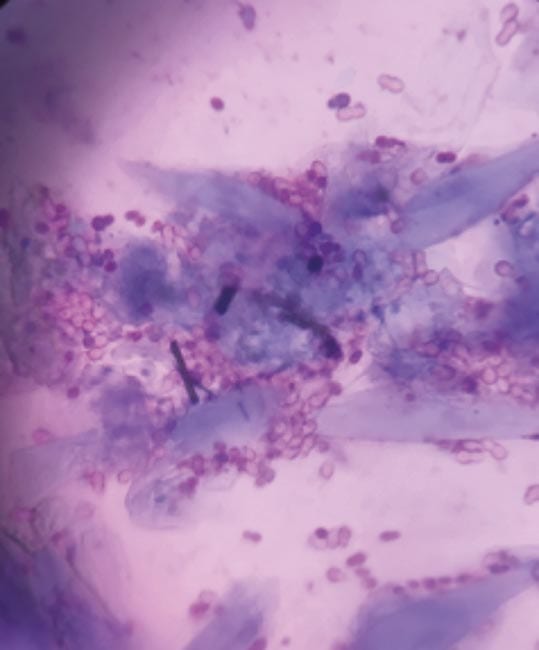

Findings: Large number of Malassezia on the paws (Figure 1; more than 15 organisms per high power field [×1,000 magnification]).

Diagnosis: Malassezia pododermatitis.

Treatment: Topical treatment for Malassezia, ectoparasite control and short course of oclacitinib for three to five days to break the itch/scratch cycle of moderate pruritus.

Re-examination: Repeat cytology performed and Malassezia pododermatitis had resolved, but pruritus recurred once oclacitinib stopped.

Reflection: Given the distribution of clinical signs, you suspect the patient has underlying environmental atopic dermatitis. As this patient had a four-month history, it was unclear if seasonal or non-seasonal disease existed. In the meantime, clinical signs could be controlled with antipruritic medication, as required, to determine the pattern of disease. Once any pattern of seasonality has been determined then allergy testing for identification of allergens for allergen-specific immunotherapy may be indicated. Patients should not be kept on antipruritic treatment long term without regular review, as it will then be very difficult to determine if the patient shows seasonality.

Three-year-old male neutered Labrador retriever with a two-week history of pedal pruritus. No routine ectoparasite control.

Clinical exam: Moderate erythema (Figure 2a) of the paws and concave pinnae, with scant cerumen in the vertical canals. Aural pruritus observed during consult.

Differentials: Ectoparasites (Trombicula autumnalis; Otodectes cynotis; Sarcoptes scabiei), infections (bacterial +/- fungal), atopic dermatitis (environment +/- food).

Diagnostics: Cytology using acetate tape (Figure 2b) from the palmar aspects of the paws and concave pinnae, as well as cytology using cotton bud from the vertical/horizontal canal junction. During sampling small, mobile, orange mites are observed in the cutaneous marginal pouch (Henry’s pocket) and interdigital area, and several collected on acetate tape for microscopic examination.

Findings: Small numbers of Malassezia organisms found in both ears and on the fore paw in small numbers. Parasites identified as T autumnalis.

Diagnosis: T autumnalis and Malassezia otitis and dermatitis.

Treatment: Topical fipronil spray on the paws used every 7 to 14 days off-licence20. Topical glucocorticoids, such as hydrocortisone aceponate, can also be used to reduce erythema and pruritus.

Re-examination: T autumnalis no longer present and repeat cytology showed absence of Malassezia. Pruritus had resolved with treatment.

Reflection: Malassezia was likely secondary to erythema and irritation caused by parasites. Furthermore, a two-week history is not consistent with canine atopic dermatitis.

Three-year-old female neutered boxer with a history of atopic dermatitis controlled on allergen-specific immunotherapy. However, she is showing aural, axillae and pedal pruritus. Regular isoxazoline ectoparasite treatment.

Clinical examination: Moderate erythema of the pinnae, axillae and paws.

Differentials: Infections (bacterial +/- fungal), flare of atopic dermatitis (environment) or development of food-induced atopic dermatitis.

Diagnostics: Cytology from the right axilla, dorsal interdigital right fore paw and the palmar aspect of the left fore paw using acetate tape. Cotton buds for aural samples.

Findings: Samples from the ears, axillae and paws were all unremarkable.

Diagnosis: Pruritic flare of non-seasonal atopic dermatitis not associated with secondary infection.

Treatment: Short two-week course of oclacitinib was prescribed to break itch/scratch cycle.

Re-examination: Pruritus well controlled with treatment and has not recurred since treatment finished three days before.

Reflection: It is not uncommon for patients with canine atopic dermatitis to flare at different time points of the year as this disease can wax and wane. Infection and presence of ectoparasite infestation should be determined before considering the use of antipruritic/anti-inflammatory treatment.

Two-year-old male neutered West Highland white terrier with a one-year history of aural, axilla, dorsal and ventral abdomen and pedal pruritus. Diagnosed with canine atopic dermatitis, but poorly responsive to treatment with oclacitinib and two months of allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT). On regular isoxazoline treatment for ectoparasite prevention.

Clinical examination: Erythema, lichenification of the concave pinnae with moderate, malodourous yellow discharge present at the auditory canal entrance. Hypotrichosis, hyperpigmentation and lichenification of the ventral abdomen, axilla and medial forelimbs (Figure 3a). Multifocal crusts with underlying erythema were present on the dorsum. The palmar/plantar aspects of the paws were moderately erythematous.

Differentials: Infection (bacterial +/- fungal), ectoparasites (Cheyletiella, pediculosis), flea allergic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis (environment +/- food).

Diagnostics: Cytology samples were taken using acetate tape from all areas except the ears, which were sampled using cotton buds. Hair pluck and skin scrape.

Findings: Aural cytology showed mixed bacterial and Malassezia; dorsum intracellular and extracellular cocci, and neutrophils (Figure 3b); axillae and paws Malassezia and bacterial overgrowth.

Diagnosis: Otitis, bacterial pyoderma, Malassezia and bacterial overgrowth.

Treatment: Manual ear cleaning was performed in clinic to demonstrate technique and visualise tympani prior to topical medication being instilled. Chlorhexidine-containing shampoo and mousse was dispensed for twice-weekly shampoo treatment and daily mousse application to affected areas. Oclacitinib treatment was stopped.

Re-examination: After two weeks, minimal crust was present on clinical examination. Repeat cytology showed very small numbers of cocci adhered to keratinocytes. A moderate reduction of pruritus had occurred. Prednisolone at 1mg/kg daily for two weeks was dispensed to reverse lichenification and hyperpigmentation, and control pruritus (Figure 4). Once infection has fully resolved, changes may be required to the long-term treatment plan.

Reflection: This patient was on appropriate treatment, but had significant secondary infection present and chronic change. Secondary infections must be appropriately diagnosed and treated for successful outcome. ASIT is not a fast-acting treatment – it often takes 5 to 6 months for an early improvement to be noticed, and up to 12 months to full effect. Improvement may be a reduction in clinical signs, pruritus, frequency of secondary infections, reduction or cessation of antipruritic treatment.