1 May 2017

Ariane Neuber discusses the importance of a firm diagnosis and management plan for dogs affected by seasonal allergies.

Interdigital furuncles with draining tracts, erythema, alopecia and salivary staining in a dog with seasonal atopic dermatitis.

Around 10% to 15% of dogs suffer from allergic skin diseases. The majority of patients have year-round disease, although a minority show strictly seasonal clinical signs, or start off as seasonal cases, later progressing to constantly affected dogs.

Canine atopic dermatitis (CAD) can have a major impact on the quality of life of the patient and pet carer alike, and can be frustrating to treat. Lifelong management strategies need to be put in place. The first step in this process is to make a firm diagnosis. Once this has been achieved, the condition needs to be brought under control and a long-term tailored management programme can be devised.

Patients experiencing strictly seasonal symptoms most likely suffer from flea allergic dermatitis or an allergy to certain environmental pollens. Management must be personalised for each patient, taking response and undesired side effects to treatments, the owner’s physical abilities, compliance and financial commitment and severity of the clinical signs into account.

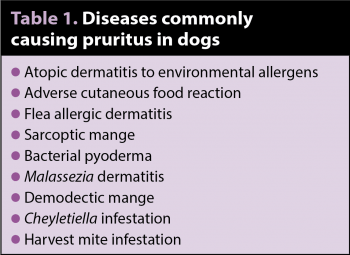

Neither allergen-specific serology nor intradermal allergy testing are tools to diagnose CAD – they merely help formulate a treatment; that is, allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT). This is because a large proportion of dogs not showing any clinical signs of an allergic skin disease show positive test results. Reliance on these tests alone to diagnose the disease would lead to similar diseases (Table 1) being missed and the patient being condemned to lifelong therapy with medication only giving limited relief for a disease that might potentially be curable (for example, fox mange) or even has the potential to deteriorate the situation (for example, glucocorticoid therapy in cases of Demodex).

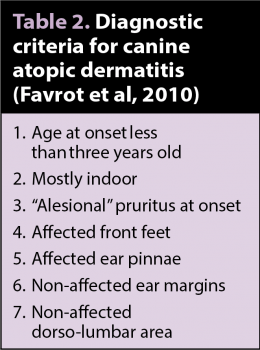

The way to diagnose an allergy is by using clinical criteria (Table 2) and excluding other diseases with diagnostic tests – and, if indicated, trial therapy. Skin scrapings can be helpful to determine if a mite infestation is present; however, if fox mange is suspected, trial therapy should be performed as the sensitivity of a skin scraping is not very high (depending on the examiner around 50%) and even the sarcoptes IgG serology – despite a much higher sensitivity of above 90% – will fail to identify a number of cases. If five criteria are fulfilled, a sensitivity of 77.2% and specificity of 83% exists. If six criteria are fulfilled, a sensitivity of 42% and specificity of 93.7% exists.

Once an allergic skin disease has been diagnosed, it may be useful to identify the offending allergens. Two big groups of allergens can be involved – those ingested (food allergy) or absorbed through the skin (environmental allergens, such as house dust mites or pollens). As a minimum requirement, it is useful to investigate the role of food in the pathogenesis of the condition, although strictly seasonal allergies are less likely to be food-induced unless certain things are only fed at certain times of the year.

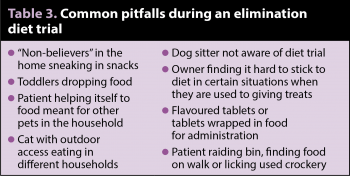

Studies have confirmed serum tests for food allergens cannot replace a dietary exclusion trial and many pet carers find it difficult to adhere to a strict exclusion of all other foods as they are used to giving treats in various situations (for example, they have a cup of tea and give the dog a biscuit, while preparing carrots a little end finds its way into the pet’s mouth, or they find it difficult to administer tablets without wrapping them in ham; Table 3).

Support during the diet trial can be very helpful – for example, follow-up telephone calls to make sure the owner is still on track or, if not, to identify the problem and suggest alternatives. Most dogs will eventually eat the food offered, albeit perhaps not with great pleasure. Reminding the owner this is only going to be a few weeks, compared to improving the quality of life over the rest of the patient’s lifespan, can help put things into perspective.

If food does not play a part in the disease for this patient, an environmental allergy is most likely. In summary, CAD is a disease diagnosed with a set of clinical criteria, which also rules out other differential diagnoses.

Once a patient has been diagnosed with allergic skin disease, a lifelong management programme needs to be implemented. Owners need to be taught how to recognise a deterioration in the condition early so more intense therapy can start before a major flare has developed. Principles of therapy include allergen avoidance, control of flare factors, topical anti-inflammatory preparations, improving the epidermal barrier function, looking after the skin, immunotherapy and, if indicated, systemic antipruritic medication.

Strictly seasonal allergies will hopefully only require therapy for a short time during the year, making glucocorticoids a viable option if the allergy season is relatively short.

Allergen avoidance (Table 4) measures can play a part in this management programme. Some allergens can lead to year-round symptoms with seasonal peaks (for example, house dust mite allergies) and some are strictly seasonal with a variety of peak seasons and length of season depending on the type of pollen involved. It might be worth following the pollen forecast, which is available from several online sources.

Control of flare factors is very important, so excellent ectoparasite control, prevention and therapy of secondary infections on their own can already help achieve a good quality of life in many affected patients. Therefore, the mainstay of therapy is topical antibacterial therapy – for example, shampoos, wipes, sprays, spot-ons, ear cleaners and mousses.

Topical anti-inflammatory preparations – such as hydrocortisone cream, hydrocortisone aceponate spray, other topical glucocorticoids, tacrolimus, pimecrolimus or other calcineurin inhibitor creams (use of these is off label) and similar preparations – can all be useful in treating individual areas that remain pruritic in the face of otherwise well-controlled patients. Long-term intermittent therapy can be helpful in keeping the inflammation under control. Hydrocortisone aceponate in particular is attractive due to its lack of systemic effects.

As part of the pathogenesis in allergic skin disease is the presence of a barrier function defect, improving said function can be used as adjunctive therapy. This can be done with topical preparations or by providing essential fatty acid supplementation.

Simply looking after the skin by performing regular therapy with a rehydrating shampoo will help remove allergens from the skin by mechanically removing bacteria, inflammatory cells, yeast organisms and their by-products, which can be helpful as adjunct therapy.

ASIT can be helpful in patients with environmental allergies. This form of therapy is the only treatment that changes the patient’s immune response to the offending allergens, is relatively cost-effective (compared to some systemic treatments), is not very labour intensive and is low in potential side effects. However, the efficacy is lower than many other forms of therapy. In a survey of patient perception of different treatments (Dell et al, 2012), ASIT was the only form of treatment owners regarded as having cured their dog in a number of cases.

In severe cases, some patients require systemic anti-inflammatory or antipruritic medication. These should ideally only be used, if still required, in cases where other treatments alone cannot achieve adequate quality of life and certainly not instead of reaching a diagnosis or instead of addressing flare factors. If the patient only suffers clinical signs for a very limited time each year, the potential for side effects is less of an issue and systemic glucocorticoids may be useful. Oclacitinib may be another drug particularly suited in these patients.

Allergies usually wax and wane all the time. This is due to a multitude of factors – some of which may not even be known to us yet. Some known factors include secondary infections, ectoparasite infestations (fleas in particular), pollen season, changes in the house dust mite population size, stress, dry skin, food triggers, amounts of allergen on the skin, environmental humidity and temperature – any combination of which may be enough to push the patient over the pruritus threshold.

CAD is commonly encountered in small animal practice. Prior to embarking on therapy, a firm diagnosis is important, which includes ruling out similar diseases. A multimodal approach is needed to achieve adequate control and give these patients the best quality of life possible. The potential for adverse side effects is less of a problem if the allergy season is relatively short.