3 Sept 2018

James Warland in the second of a two-part article, discusses levels of success for methods to overcome this common condition.

Image: Yordan Fernandez

Feline hyperthyroidism is a common condition in general practice and usually straightforward to diagnose. However, management can be challenging due to variable responses, owner preferences, side effects and comorbidities – necessitating an individualised approach to each case and careful explanation of options to owners. In part one (Focus; VT48.27), comorbidities, particularly renal disease and hypertension, were covered. This part will discuss treatment options for feline hyperthyroidism with the aim of optimising treatment success for patients. The identification and management of iatrogenic hypothyroidism will also be discussed.

The management of hyperthyroidism, even for relatively ”simple” cases, can be challenging, owing to a bewildering array of treatment options often associated with varied outcomes, challenging side effects, difficulties in administration and expense.

Treatment options should be tailored to individual patients. In part one of this article (VT48.27), the concurrent management of hyperthyroidism and renal disease was discussed. Hyperthyroidism appears to be detrimental to renal health, and attempting to ”undertreat” these cases is no longer recommended, although care must be taken to avoid iatrogenic hypothyroidism.

Most cases of hyperthyroidism are due to adenomatous hyperplasia of the thyroid gland(s), and can be broadly treated with dietary, medical (antithyroid medication or radioactive iodine) or surgical management. Uncommonly, thyroid carcinoma is reported, which is likely more appropriately treated with surgery or high dose radioiodine. Thyroid cysts (benign or malignant) can be treated with surgery or radioiodine, or a combination1.

It is increasingly common to encounter cats with very mild, or no, clinical signs of hyperthyroidism, due to owner (mild signs) or clinician diligence (thyroid nodule), or via wellness blood screening. These cases can seem particularly challenging, as performing surgery, radioactive iodine treatment or starting life-long medication can feel overzealous.

Assuming the diagnosis has been confirmed, ideally through repeat thyroxine (T4) measurement at an external laboratory, the author would recommend these cases are treated for their hyperthyroidism. The hyperthyroid state is progressive, and deleterious to renal and cardiovascular health, so treatment should be undertaken; any of the treatments recommended for symptomatic cases are appropriate. These mild cases are likely to be the most amenable to dietary management, if compliance can be ensured.

Most first-opinion clinicians’ preferred treatment is oral medical treatment (66%), with surgical thyroidectomy (28%) and radioiodine (5.5%) used less frequently2; it should be noted this survey was performed before dietary management or transdermal methimazole were widely available.

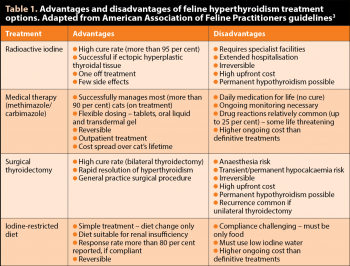

The American Association of Feline Practitioners (Table 1) has produced practical guidelines3 on the diagnosis and management of feline hyperthyroidism, which include details beyond the scope of this article.

Treatment with radioactive iodine (131I) is considered by most specialists to be the gold standard approach to hyperthyroidism. Cure rates are more than 95%, although controversy exists as to optimum dosing for cats. Survival times are typically excellent, with medians reported of three to four years4,5. Key advantages of radioactive iodine therapy (RIT) include high permanent cure rates without further treatment needed, treatment of extra-thyroidal tissue and few side effects. The disadvantages are periods of hospitalisation (one to three weeks depending on the centre), high upfront cost and lack of reversibility.

In a UK survey, the vast majority (92%) of owners of cats treated were happy with the choice of radioiodine therapy, and the major barrier to treatment was concern about hospitalisation time, and concern about missing their pet or their cat being unhappy6. Interestingly, in owners not pursuing radioiodine treatment, the most common reason was lack of awareness of the treatment.

Hypothyroidism is reported in up to 75% of cases, although this is dose dependent3, and lower rates are reported (1% clinical; 21% subclinical) in studies using lower doses of iodine-131 (131I), which still appear to adequately treat the condition7. Owners must be adequately counselled about the possibility of iatrogenic hypothyroidism, which may require supplementation, particularly as many owners choose RIT for a ”medication-free” future.

Two licensed oral antithyroid medications are available for cats – methimazole/thiamazole and carbimazole – which act to block the biosynthesis of thyroid hormones. Carbimazole is the pro-drug of methimazole. These medications can be effectively used to control hyperthyroidism, with most becoming euthyroid in two to three weeks. Oral methimazole appears more effective given twice daily rather than once daily8, the recommended regimen, whereas carbimazole can be effectively given once daily, with similar efficacy9. The introduction of a liquid preparation can be valuable in improving compliance in cats that cannot be medicated with tablets.

Initiation of medical treatment is typically more ”gentle” than historic recommendations, with the aim of avoiding hypothyroidism. Typical starting doses are 1.25mg/cat to 2.5mg/cat twice daily for methimazole and 10mg/cat once daily for carbimazole. Dose adjustments are more flexible with methimazole, given the tablet sizes and availability of a liquid formulation, and should be 1.25mg/cat/day to 2.5mg/cat/day after assessment at three weeks. The aim should be to maintain euthyroid status, without over or under-suppression of thyroid function.

Transdermal administration of methimazole is becoming increasingly popular and may be a more convenient route of administration for many owners. It is typically applied once or twice daily to the inner pinnae. It appears to be efficacious with similar doses to oral treatment, although it appears there may be more variability in compliance and thyroid concentrations10. Other reports suggest success rates are lower and slower than with oral treatment (67% versus 82% euthyroid at four weeks)11.

It should be noted transdermal methimazole is not licensed and clinicians must justify its use over oral therapy to use it under the cascade. Owners should be aware of potentially increased exposure to methimazole, which is a known teratogen; gloves should always be worn when applying the product, and it should not be handled by pregnant or breastfeeding women. For the same reason, tablets should not be crushed or split, and gloves should be used when handling methimazole. Environmental exposure of methimazole is likely to be higher with the transdermal formulation.

Side effects are relatively common, ranging from relatively mild – gastrointestinal (GI) upset, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea (10% to 25%; oral treatment) – to severe facial excoriations (2% to 12%), and can be life threatening, such as blood dyscrasias (neutropenia, anaemia and thrombocytopenia; up to 9%), bleeding diatheses, myasthenia gravis and hepatopathy (less than 5%)11,12. All these side effects can be seen with oral or transdermal methimazole or oral carbimazole, but GI side effects are typically less common (less than 5%) with transdermal application10.

The presence of potentially severe side effects means cats should be monitored carefully, particularly during the first three months of therapy, when most side effects are seen. Serum biochemistry and haematology should be checked when rechecking total T4 (TT4) and the owners questioned on other side effects, such as GI signs or pruritus. Switching to transdermal treatment can reduce GI side effects.

Severe side effects should lead to immediate cessation of therapy, which is usually sufficient to reverse the signs; discussion with an internal medicine specialist is recommended in severely affected cats or those not improving with cessation of therapy. Some cats treated with transdermal methimazole will develop erythema/irritation at the application site, which can be resolved with switching to oral therapy10. While no direct comparisons have been produced, given their similar actions, it seems ill-advised to treat a cat that has suffered side effects to methimazole with carbimazole, or vice versa.

Surgical thyroidectomy is associated with cure in more than 90% of cases, if performed by an experienced surgeon13. Euthyroidism is usually achieved quickly, within 24 to 48 hours of surgery. If unilateral surgery is performed then around 30% to 60% of cases may recur in the contralateral gland3. The main cause of recurrence after bilateral thyroidectomy is the presence of ectopic hyperplastic thyroidal tissue, which is reported in up to 9% of cats13.

Surgery can be performed by most general surgeons, although experience with the technique is likely to improve outcomes. The main risks of surgery are the anaesthetic and postoperative hypocalcaemia, which occurs either transiently or permanently due to damage to the parathyroid glands. Reported incidence is variable (6% to 82%) and is more common with bilateral surgery.

Postoperative hypocalcaemia is usually transient, but potentially life-threatening, and cats must be adequately monitored after surgery. Cats that develop hypocalcaemia should receive vitamin D supplementation (such as alfacalcidol), and may require emergency IV calcium (boro)gluconate if symptomatic. Thyroidectomy may cause hypothyroidism, which can be transient (unilateral surgery) or permanent (bilateral surgery). Other risks reported include Horner’s syndrome and laryngeal nerve paralysis.

A commercial iodine-restricted diet is available for the management of hyperthyroidism. The key advantage of this approach is it requires minimal intervention for the patient. The diet reduces circulating TT4 concentrations to within reference range in 64% and 75% of cats in four and eight weeks, respectively, and owners reported an improvement in clinical signs of hyperthyroidism within four weeks, with no obvious side effects14.

Another study showed similar improvements in TT4 concentrations, and found that initial TT4 concentration was linked to the likelihood of normalisation – less severely affected cats were more likely to respond15. In this study, despite the decrease in TT4, clinical improvement was inconsistent and no difference was found in bodyweight or heart rate after treatment, although remission lasting at least a year in 83% of cats was documented.

Dietary management requires strict compliance, including consideration of cats eating treats, water supply (must be low iodine), other medications or finding food elsewhere, so is unlikely to be appropriate for many patients. Multicat households may struggle to achieve compliance, although a study has suggested normal adult cats can be safely fed the diet if it is necessary to change the diet of all cats16. Palatability appears to be generally good, with 88% accepting the change14. Interestingly, several studies have shown decreases in creatinine on dietary management, so it appears to be safe in renal insufficiency14,15; the manufacturers have designed the diet to be appropriate as a ”renal diet”.

In the author’s experience, diet management is most appropriate in relatively mildly affected, indoor cats, where compliance can be ensured.

Homeopathic treatment of hyperthyroidism has been advocated by some, but a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed no efficacy in this approach17, so it cannot be recommended.

It is vital to monitor physical condition after treatment, particularly considering possible side effects and evidence of treatment efficacy (such as weight gain and appetite). TT4 should be checked around three to four weeks after definitive treatment or dose adjustments then rechecked at three and six months.

When using medical therapy, TT4 should be targeted to the lower half of the reference interval. If TT4 is below the reference interval, medical dosing should be reduced. Low TT4 is commonly seen one month after RIT and this often normalises over the subsequent months. This temporary, subclinical, hypothyroidism is unlikely to be clinical significant unless renal disease is present or clinical signs develop, in which case hypothyroidism should be treated with supplementation. Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) can be used alongside T4 to diagnose hypothyroidism.

Serum biochemistry and urinalysis should be checked to monitor renal function. In cats receiving medical therapy with methimazole/carbimazole, haematology should be checked, alongside biochemistry, to rule out blood dyscrasias and hepatopathy.

Blood pressure should be monitored before and after treatment for hyperthyroidism. Many cats will be normotensive at diagnosis and develop hypertension subsequently. Management of renal disease and hypertension in hyperthyroid cats was discussed in part one.

Iatrogenic hypothyroidism can develop after radioiodine therapy or surgical thyroidectomy. Overzealous medical management can lead to hypothyroidism, reversible with reduction/cessation of therapy.

Temporary hypothyroidism is common following radioiodine, with low TT4 measured after one month, and this usually requires no further therapy as the residual function will improve over the subsequent three to six months. Reported prevalence of permanent iatrogenic hypothyroidism depends on radioiodine dose and the criteria used for diagnosis, meaning it is hugely variable from 5% to 83%18.

Clinicians should aim to clinically control the cat’s signs, with the TT4 in the lower half of the reference interval. TT4 levels below this should generally be avoided. The diagnosis of hypothyroidism can be challenging as clinical signs, such as weight gain, can overlap with normal recovery from hyperthyroidism; and many euthyroid cats have concurrent disease, leading to euthyroid sick, low T4 levels. TSH has been shown to be more sensitive and specific for the detection of hypothyroidism, and measurement of TSH should be performed where hypothyroidism is suspected19.

Clinical signs include bradycardia; significant weight gain despite poor appetite; lethargy or mental dullness; constipation; and dermatological changes, including poor quality, dry, dull or scurfy coat, easy epilation, poor hair regrowth after clipping and alopecia of the pinnae (Figure 1). Some cats will have T4 concentrations within the reference range, so hypothyroidism should not be discounted with a normal T4. In cats showing clinical signs or that are azotaemic, the author measures TSH if the T4 is in the lower 25% of the reference interval. Unless early post-treatment, the diagnosis can be confirmed with a low-normal or low T4/free T4 and concurrent high TSH.

The author would not diagnose iatrogenic hypothyroidism in a well, non-azotaemic cat until at least three to six months after definitive therapy (radioiodine or thyroidectomy), given the high prevalence of transiently low T4 of little clinical significance and expectation that TSH will rise after treatment. The diagnosis should be pursued sooner in azotaemic cats, as evidence exists that iatrogenic hypothyroidism shortens survival times, and correction is important to improve renal function. In these cats, temporary treatment while transient hypothyroidism resolves would be indicated.

Treatment of iatrogenic hypothyroidism is to reduce methimazole/carbimazole dose, if the cat is receiving it, or supplement with levothyroxine (10μg/kg/day to 20μg/kg/day), which can be adjusted to maintain normal T4 and TSH. If iatrogenic hypothyroidism is permanent then treatment must be continued for life.

Hyperthyroidism treatment can be challenging due to the variety of options, and their advantages and disadvantages. Radioactive iodine is considered the ”gold standard”, but relatively long hospitalisation and upfront costs mean it is not appropriate for all cases. It is likely, over the course of their lives, all the treatment options (drug therapy, diet, thyroidectomy and RIT) cost a similar amount.

The introduction of different medical formulations (transdermal, oral liquid) have allowed for better medical treatment of cats that are difficult to medicate, giving greater flexibility to owners and clinicians. With all treatments, concurrent renal disease and hypertension must be considered and managed. Iatrogenic hypothyroidism is an important complication of treatment, particularly if renal insufficiency is present, and clinicians must recognise and treat this where necessary.

Thanks to Mini Wright and Tim Williams for their critical appraisal of the article and suggested improvements. The author is also very grateful to David Williams, Yordan Fernandez and Mini Wright for photographs used in illustrations.