18 Jan 2016

Figure 1a. Examples of lysed cells due to excessive smearing. Cells cannot be identified.

Cytological evaluation of solid masses, lymph nodes, internal organs and body fluids is an effective means for diagnosing many inflammatory and neoplastic disorders in dogs and cats.

The interpretation of cytological samples relies on the understanding of the most common diseases that occur in these animals and on the familiarity with the most typical cytological features that characterise each of these conditions.

The main advantages cytology offers to daily clinical work are the ease of obtaining samples with the minimal risk of complication and rapid results.

Different factors can have an impact on the quality of a sample, including the following.

Excessive suction aspiration or smearing of the sample can damage the cells (Figure 1a). The use of a small gauge needle without an attached syringe is generally preferred and use of suction aspiration should be restricted to poorly exfoliative masses.

The lesion can be missed and cells can be aspirated from the surrounding tissue. The positioning of the needle in the lesion is critical for collection of a diagnostic sample.

Aspiration of representative tissue cells can be more difficult from haemorrhagic, necrotic or cystic masses. Multiple areas of the lesion should be sampled to increase the probability of obtaining a representative sample. The centre of large masses is often necrotic and can yield amorphous cellular debris and inflammatory cells. Aspiration from the edges of the lesion should be preferred (Figure 1b).

Masses with an abundant collagenous stroma tend to exfoliate poorly (for example, some types of spindle cell tumours).

Insufficient staining of the sample hampers an accurate examination of the cellular details. Under-staining of the specimen can be due to old stains, the presence of excessive cellular material on the slide or the presence of large quantities of ultrasound gel.

The exposure of unfixed cytological samples to formalin fumes leads to loss of cellular and nuclear detail that often makes interpretation difficult.

It is also important to always interpret the cytological findings in conjunction with the clinical presentation, the location of the lesion (for example, cutaneous or subcutaneous) and its macroscopic appearance. The attempt to over-interpret poor quality smears could lead to a wrong cytological conclusion.

As in every other discipline the use of a logical and systematic approach is helpful when examining a cytological sample. Following a step-wise fashion diagnostic process (as shown in Figure 2) reduces the chance of missing important information or reaching wrong interpretations.

Once it has been established the sample is of good quality, the cytologist’s aim is to identify the nature of the lesion and, in particular, differentiate between a hyperplastic, neoplastic or inflammatory condition. The distinction between these categories is simple when only tissue cells or inflammatory cells are present; however, this becomes more difficult when a lesion is composed by a mixture of inflammatory and tissue cells.

Scanning the slide at low power magnification (4× and 10×) is useful to find spots of specimen in the less cellular aspirates and evaluate the cell arrangement. The way the cells are spread on the slide in relation to another offers a useful clue that helps in identifying the tissue of origin. The individual cell morphology is also essential to recognise the histotype of the tissue. The cellular morphological features are usually evaluated at a higher power of magnification (40×, 50× or 100×).

When tissue cells are aspirated they should be differentiated between normal, hyperplastic, dysplastic or neoplastic cells and classified based on the tissue of origin (epithelial, mesenchymal or round cells).

Epithelial cells usually exfoliate in cohesive clusters characterised by having smooth edges. They usually have well defined cytoplasmic margins and the junction between contiguous cells may appear as a thin, clear line. Nuclei are generally round. Depending on the organ or tissue of origin, epithelial cells can be polygonal, cuboidal or columnar (ciliated or non-ciliated) and arranged in pavement, acinar, papillary, palisade, trabecular or honeycomb patterns (Figures 3 and 4).

Mesenchymal cells are usually found individually or in non-cohesive aggregates with jagged contours. The classical mesenchymal architectural arrangements are storiform and perivascular (Figures 5a and 5b). Depending on the tissue of origin and degree of cell differentiation, mesenchymal cells can be spindle shaped, fusiform to plump oval, stellate or veiled (Figures 5c and 5d).

Round cells from round cell tissues are not cohesive so exfoliate well and are found as individual round or oval cells, with round to oval, occasionally convoluted, nuclei. Cell margins are very distinct. Examples of round cells are lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes and mast cells (Figure 6).

Inflammatory lesions are sub-classified the predominant inflammatory cell type or based on their proportion. This helps in listing the more likely differential diagnoses of the causative agents.

The co-presence of tissue cells and inflammatory cells can represent a cytological challenge as, on some occasions, it is difficult to distinguish between a neoplasia with secondary inflammation from a primary inflammatory process causing tissue cell dysplasia. In these cases, histopathological examination is usually used for a definitive diagnosis.

As discussed earlier, the first step in tumour cytology is to recognise whether the neoplastic cells are epithelial, mesenchymal or round. In poorly differentiated and anaplastic tumours, the cell of origin of the neoplastic population often cannot be recognised. In these cases, histopathology, and often immunohistochemistry, are needed to identify the histotype of the tumour.

The next step is to differentiate between a benign and a malignant proliferation. Identifying those morphological alterations the neoplastic cells display, if compared to the “normal” cells (criteria of malignancy), helps in differentiating between a benign or malignant process. The criteria of malignancy used on cytology for this purpose are the following (Figure 7).

The most common alterations in tissue organisation recognised on cytology include cell crowding (loss of contact inhibition) and loss of cell cohesion.

One or more nuclear atypical features can be found – examples include anisokaryosis, karyomegaly, multinucleation, nuclear blebbing or fragmentation, prominent nucleoli of variable size and/or shape, coarse chromatin, thickened nuclear membrane and increased or abnormal mitotic activity.

Examples of cytoplasmic criteria of malignancy include increased basophilia, presence of abnormal inclusions or vacuoles and anisocytosis.

Unfortunately, the identification or absence of various criteria or malignancy does not always correlate with the biological behaviour of a tumour. There are very well-known aggressive tumours characterised by their lack of malignant features – examples include anal sac adenocarcinoma, thyroid carcinoma and some neuroendocrine tumours.

Inflammatory processes are characterised by the presence of one or different types of inflammatory cells and this greatly depends on the causative agent involved and the duration of the inflammation. The most common types of inflammations are the following (Figure 8).

Neutrophilic inflammation is characterised by a large predominance of neutrophils. It can be caused by bacterial infections, irritants or necrosis. As a general rule, in a septic neutrophilic inflammation, neutrophils are degenerate while they are not in sterile processes. Neutrophilic degeneration caused by bacterial endotoxins is usually shown as reduced nuclear lobulation and nuclear swelling (defined as karyolysis). In septic inflammations, often, but not always, intracellular bacteria can be identified.

Eosinophilic inflammation is usually found in the course of a hypersensitive or parasitic disorder and can be found as a paraneoplastic response (for example, mast cell tumour and T-cell lymphoma).

Pyogranulomatous inflammation is composed mostly by neutrophils and macrophages, with lower numbers of other inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells. It is caused by a chronic insult as fungal infection and endogenous or exogenous foreign body reactions.

Granulomatous inflammation is characterised by a large predominance of macrophages with lower numbers of multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes and plasma cells. Differential diagnoses include some types of bacterial infection, such as mycobacteriosis and fungal infections.

The most common skin and subcutaneous lesions that can be sampled by fine-needle aspiration in dogs and cats are inflammatory processes, tissue injuries and tumours (benign and malignant).

The following are examples of cutaneous and subcutaneous neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions more frequently encountered in everyday small animal clinical practice.

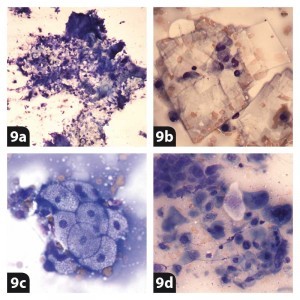

Aspirates from epidermal/follicular inclusion cyst lesions (Figures 9a and 9b) usually exfoliate numerous anucleated squamous epithelial cells in a proteinaceous background. Variable numbers of cholesterol crystals and occasional hair shafts can also be found.

A sebaceous adenoma/hyperplasia tumour (Figure 9c) is a common skin benign tumour in older dogs. Cytology is characterised by the presence of well-differentiated sebocytes. These cells have a small, round and central dense nucleus and abundant and heavily vacuolated cytoplasm.

A trichoblastoma (Figure 4c) is a benign tumour that can occur in dogs and cats. It is composed of basal cells often arranged in typical palisading structures. Cells have a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio with round nuclei and a small amount of cytoplasm. The chromatin is often finely clumped and nucleoli are not seen.

A squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; Figure 9d) is a common malignant tumour that affects dogs and cats. In cats it typically arises from less pigmented areas such as the nasal planum and eyelids. Neoplastic cells are polygonal with a variable nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. Nuclei are round and central. The chromatin can vary from being finely clumped to coarsely stippled.

Nucleoli are usually seen in the less differentiated forms of SCC. The cytoplasm can be scant to abundant, lightly to deeply basophilic and this depends on the degree of maturation of the cells. These tumours often elicit a prominent neutrophilic response.

Lipoma (Figure 10a) is a very common subcutaneous tumour in dogs. It has a poor exfoliative tendency and aspiration yields well-differentiated adipocytes. These cells have a small, dense nucleus and abundant cytoplasm containing a large, clear lipidic vacuole. Cells can be found individually or in variably sized aggregates.

Opposed to other mesenchymal tumours, perivascular wall tumours (Figure 10b) usually have a high exfoliative nature. Cells are individual or in aggregates and can be mono, bi or multi-nucleated (typically found as crown cells). The cell morphology is variable from spindle shaped, stellate or veiled and cells often have fringed margins. Their cytoplasm is lightly to moderately basophilic and can contain small, clear, punctate vacuoles.

On aspiration, fibrosarcomas (Figure 10c) usually give a poor cell harvest. In well-differentiated fibrosarcomas, neoplastic cells are spindle shaped with medium to large oval nuclei and two cytoplasmic tails that project away to each side of the nucleus; the less differentiated the tumour, the more the cells become plump to oval and pleomorphic. Bi and multinucleated cells can be found with variable frequency.

Benign and malignant cutaneous melanocytic tumours (Figure 10d) are relatively common in dogs and rare in cats. Benign tumours exfoliate high numbers of relatively uniform cells that contain numerous green to black melanin granules. Malignant melanomas are more pleomorphic and are often less pigmented. In dogs, the majority of the melanomas originating from haired skin are benign, whereas the majority of melanomas arising in the oral cavity, nail bed and mucocutaneous junctions are malignant and often amelanotic.

Cutaneous mast cell tumours (Figure 6a) are common in dogs and cats. Fine-needle aspirates are generally highly cellular and yield a population of discrete granular cells. In well-differentiated mast cell tumours, cells contain numerous purple granules, while poorly differentiated forms are more pleomorphic and less granular. Granules can be confined in focal areas of the cells.

Histiocytoma (Figure 6b) is a benign tumour that most commonly, but not exclusively, occurs in young dogs. It often spontaneously regresses and usually exfoliates high numbers of round cells. Their nuclei are medium to large, round to oval or bean shaped and paracentral. The amount of cytoplasm is moderate and lightly basophilic. Occasionally, it can contain small phagosomes. Variable numbers of lymphocytes can often be found in the aspirates.

Plasma cell tumours (Figure 6d) exfoliate numerous plasma cells. They are characterised by a moderate amount of deeply basophilic cytoplasm with a perinuclear clearing. The nucleus is eccentric and round with granular chromatin and indistinct nucleoli. Binucleated cells and moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are frequently observed. Plasma cell tumours usually have a benign biological behaviour and carry good prognosis following excision.

Transmissible venereal tumour is a sexually transmitted neoplasm mostly affecting the external genitalia in dogs. It is uncommon in the UK. Cells are round and have moderate amounts of lightly basophilic cytoplasm, frequently containing small, clear punctate vacuoles. The nuclei are round and paracentral.