8 Dec 2020

Krzysztof Herman DVM, PGCertSAS, MRCVS describes the surgical treatment of a patient using a combination of suture anchor and external skeleton fixator.

This case report describes an 11-and-a-half-year-old female neutered domestic shorthair cat with an avulsion of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle.

A diagnosis of avulsion was made based on clinical examination and radiographic assessment. Surgical reduction and fixation was achieved using two modified three-loop pulley sutures attached to a 2.5mm suture anchor. A temporary trans-hock external fixator was used to neutralise forces on the gastrocnemius muscle.

No postoperative complications were encountered. Follow-up at four months showed a normal limb function and the patient continued normal outdoor activities.

This is the first report of treatment of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle avulsion in a cat using a combination of suture anchor and external skeleton fixator, and the third case of such injury described in general.

Injuries to the Achilles mechanism are common in cats and dogs, but in the majority of cases the common calcaneal tendon1-4 is affected, rather than the proximal origin of the gastrocnemius muscle5-12.

To the author’s knowledge, this injury in a cat was described in two case reports13,14, but it is the first case report to present treatment of this condition with the use of a transarticular external fixator and suture anchor.

This case report describes diagnosis, treatment and outcome of this technique.

An 11-and-a-half-year-old female neutered domestic shorthair cat was referred for assessment due to severe left hindlimb lameness sustained six days previously during outdoor activities.

Examination revealed severe weightbearing lameness of the left hindlimb with a plantigrade stance. The toes were curled slightly downwards. Palpation of common calcaneal tendon was unremarkable and no wounds were detected on the skin. Tibial thrust and cranial drawer tests were negative, but a sign of discomfort was noted during palpation of the left lateral fabella. The rest of the neurological and orthopaedic examination was unremarkable.

According to the owner, the patient was extremely active and spending the majority of time outdoors.

Orthogonal radiographs of the left stifle joint were taken (Figures 1 and 2), showing distal displacement of the left lateral fabella. Further flexion of the hock showed even greater displacement of the fabella (Figure 3).

Following radiographs, the left hindlimb was routinely prepared for surgery.

The patient was given acepromazine (0.02mg/kg IM), methadone (0.15mg/kg IM), meloxicam (0.01mg/kg SC), cefuroxime (20mg/kg IV) and an epidural injection of preservative‑free morphine (0.2mg/kg) diluted in saline (0.2ml/kg).

Anaesthesia was induced with alfaxalone (IV to effect), and maintained with isoflurane and oxygen.

The cat was positioned in dorsal recumbency and four-quadrant draping was performed. A lateral approach to the stifle was performed15 and avulsion of the gastrocnemius muscle confirmed.

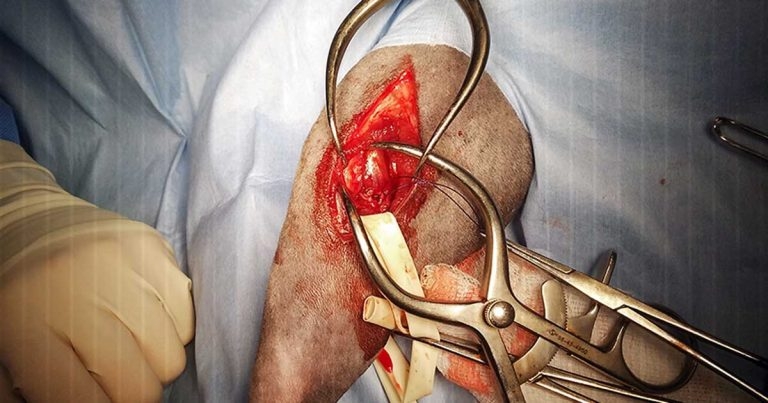

As the common peroneal nerve was visible in the surgical field, the nerve was retracted and protected with a small Penrose drain (Figure 4). A 2.5 mm suture anchor was engaged in lateral condyle at the level of the tendon insertion.

The lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle was repositioned as close as possible to its origin by using 0 metric polydioxanone suture. Attachment points were as follows: proximally – suture anchor, and distally – around the lateral fabella.

A three-loop pulley technique was used. Two separate loops of the suture were placed and the suture anchor was tightened. The wound was flushed and closed routinely.

A type 1A, transarticular, external skeletal fixator (ESF) was placed on the medial aspect of the distal limb. Two 2mm positive and one 1.8mm positive pins were placed in the tibia, with a 1.6mm positive pin in the central tarsal bone – as well as across proximal heads of metatarsal bones – and two 1.6mm negative pins in the second and third metatarsal bones.

Postoperative radiographs (Figures 5 and 6) showed satisfactory implant positioning and reduction of the fabella.

The patient was discharged the following day with meloxicam (0.1mg/kg orally once daily for three weeks) and amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (12.5mg/kg orally twice daily for 10 days). Strict exercise restriction was recommended, and the patient was rechecked every two weeks for temporary ESF removal and physiotherapy (range of motion exercise under sedation).

Six weeks post-surgery, orthogonal radiographs confirmed maintaining of the lateral fabella in a satisfactory position. The ESF was removed and house rest was recommended. No complications were noted during the first six weeks and good use of the limb was reported at the time of frame removal.

Four weeks after frame removal, the patient was re-examined. Clinical examination showed full limb use without a plantigrade stance.

Final follow-up was performed via telephone conversation five months post-surgery. The owner reported full recovery and provided a video of the cat walking outdoors.

Avulsion of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle has only been reported in two cases13-14. The first case was treated with primary repair and tibiocalcaneal screw, and the second with suture anchor and stifle flexion device. Both cases made a full recovery.

In reported cases, two canine patients that were supplemented with external coaptation experienced failure of a repair and needed revision surgeries.

Conservative treatment and the use of therapeutic ultrasound were described in two dogs12; however, these cases had partial gastrocnemius avulsion.

In view of severe fabella displacement, the author advised surgical treatment. Based on previous reports in canine patients, repair using suture anchor and ESF was recommended. This combination in a feline patient had not been previously described.

Monofilament and suture anchor was used instead of a bone tunnel and wire to minimise the effect of cycle load and failure of the wire. Further to this, to help reduce the chance of failure of the repair, a trans-hock ESF was used.

In previously described cases of gastrocnemius avulsion repair in cats, a tibiocalcaneal screw and stifle flexion device were used as supplementary protection. Although the stifle flexion device looks very interesting, the author does not have experience with this method and minimal scientific evidence exists in the veterinary literature supporting this method.

The author chose ESF as he was more comfortable with this method of fixation compared to the tibiocalcaneal screw.

ESF has the benefit of allowing temporary removal of the frame to perform physiotherapy under sedation. It was hoped this would help increase joint fluid circulation and minimise the chance of cartilage damage caused by joint disuse16.

The downsides of ESF are premature pin loosening and pin tract infections. Usually, such complications are classed as minor complications and could be successfully managed with medical treatment.

Lateral avulsion of the gastrocnemius muscle can be treated successfully by a combination of two commonly used surgical techniques. The patient made a full recovery without complications.