31 Dec 2019

Michelle Clark BVSc, CertAVP(SAM), MRCVS and Helen Baxter BVMS, CertAVP, MRCVS discuss this procedure and share a case study involving a dog kicked by a horse.

Autologous blood transfusion (ABT) is defined as the transfusion of the patient’s own blood collected from an active or recently bleeding site, via a filtered giving set, to help restore haemodynamic stability in an emergency setting.

ABT is commonly performed in human medicine (Robinson et al, 2016) – and as the donor and recipient are identical, the risk of a transfusion reaction is limited.

In veterinary medicine, the procedure is particularly useful in the surgical emergency setting in general practice, where access to blood products may be limited and financial concerns may exist.

Arguably, the most appropriate use of an ABT is that of a coagulopathic, traumatic or postoperative haemoabdomen or haemothorax, where stored blood products do not exist or are unable to be sourced in time.

In these cases, ABT provides rapid blood components and intravascular volume, while definitive haemorrhage control is achieved.

Use of ABT has also been documented in anticoagulant rodenticide toxicities. In a review of 25 cases, Higgs et al (2015) reported 100% survival post-ABT in those patients with a coagulopathy, 71% in cases of vascular trauma and 50% in cases with a ruptured neoplasm.

The benefits of ABT include:

ABT cannot be performed where contamination is suspected, such as uroabdomen, septic peritonitis or bile peritonitis.

Debate is ongoing around the use of ABT in cases where a ruptured neoplasm is suspected due to the potential risk of introducing neoplastic cells into the circulation.

In human medicine, passing autologous blood through a leukoreduction filter prior to transfusion is an effective method of neoplastic cell removal; however, this is cost-prohibitive in general practice.

In cases where a ruptured neoplasm is suspected, a risk benefit approach should be applied when considering ABT.

In the authors’ opinion, if the alternative is exsanguination and death then ABT should be considered acceptable.

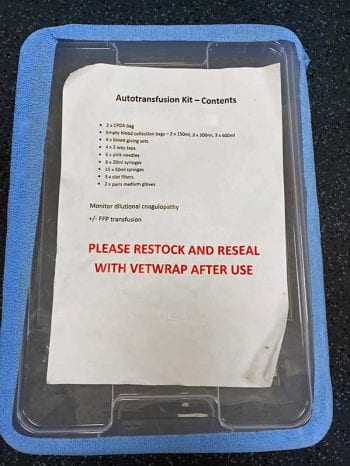

The box (Figures 1a and 1b) should include:

ABT can be performed by three methods:

When collecting blood for ABT, strict asepsis must be adhered to. Collection must be conducted carefully; excessive suction can cause haemolysis.

The use of anticoagulant during ABT is controversial. Blood that has been in contact with thoracic or abdominal serosa for more than one hour becomes defibrinated and, therefore, is unlikely to require anticoagulant.

When blood is collected from a source of rapid, active haemorrhage, the addition of anticoagulant may be warranted. In these cases, it has been suggested to use citrate phosphate dextrose (CPD) at a dose of between 25ml and 30ml per 500ml of autotransfused blood.

Hypocalcaemia has been reported in cases where blood has been reinfused with excessive citrate anticoagulant. Where CPD has been used, it is recommended to monitor ionised calcium levels and for any clinical signs of hypocalcaemia post-transfusion.

However, a study by Higgs et al (2015) found no significant association between outcome and the addition of anticoagulant to blood used for ABT.

The possible complications of an ABT are

CASE STUDY

A three-year-old cross-breed dog presented collapsed after being kicked in the side by a horse.

On examination, the dog was quite alert and responsive, mucous membranes were pale pink, heart rate was 140bpm, and peripheral pulses were weak. Blood pressure was 64mmHg and PCV was 35%.

Point-of-care ultrasound showed free abdominal fluid that was consistent with a haemoabdomen on abdominocentesis. Thoracic-focused assessment with sonography for trauma was negative for free fluid.

A body bandage was applied and crystalloid fluid resuscitation was started at 20ml/kg over 10 minutes. After 30 minutes, the patient’s PCV had dropped to 25%.

An exploratory laparotomy revealed the left kidney to be severely damaged and avulsed into the abdomen (Figures 2a and 2b). A large split was also seen in the main body of the spleen (Figure 3), which was actively bleeding. A large volume of free abdominal blood was evident.

The blood was collected via a sterile 50ml syringe and placed into a blood collection bag ready for transfusion. As this process was performed, the patient’s blood pressure dropped below 60mmHg.

The blood collected was given to the patient as a free-running bolus, while maintaining crystalloid IV fluid rates of 5ml/kg/hr.

A left-sided nephrectomy and splenectomy were performed. Once active bleeding was stopped, the blood pressure stabilised at 100mmHg.

The patient recovered well from the surgery and the following morning a PCV of 28% was recorded. The patient was discharged after 24 hours and made a full recovery.