6 Feb 2017

Scott Rutherford discusses a variety of management options for this common arthritic condition seen in canine patients.

Figure 1. An intraoperative photograph of a stifle joint showing osteophytosis.

OA is the most common condition causing pain and disability in dogs, and is almost always secondary. Elimination of the inciting cause is rarely – if ever – possible and the secondary OA has no cure. It can be difficult to manage and requires a significant time commitment from everyone involved, which can lead to dissatisfaction, poor compliance and management failure. This results in frustration for the pet owner and the vet, leading to a vicious cycle of treatment failures and deepening frustration. Its treatment is complicated by the variety of possible treatments available – some of which have evidence of efficacy and some of which have, at best, anecdotal stories of success. This leads to much confusion and can result in wasted time and money.

A multimodal approach combines lifestyle management, medical, surgical and other methods to successfully manage the disease throughout the dog‘s life. If instigated promptly and used in a planned, organised way, most dogs with OA can be kept happy and active throughout their lives, without having to resort to drastic measures such as euthanasia.

This article should help demystify the many different available treatments and allow you to improve the management of the challenging OA case.

OA is the most common form of arthritis in the dog and it is estimated 20% of the population is affected1.

OA can be defined as the aberrant repair and subsequent degradation of articular cartilage with concurrent changes in subchondral bone metabolism, periarticular osteophytosis and synovitis (Figure 1).

It is important to remember the synovial joint is an organ and injury to one component affects the others. As well as accepting OA affects a joint globally, it is also accepted dogs with OA are in a chronic pain state, which is harder to identify and treat than acute pain2. Joint pain results in the development of central sensitisation3, and growing evidence suggests central sensitisation actually drives the progression of OA, such that modulation of this can decrease joint pathology4.

In dogs, OA is almost always secondary to an initiating abnormality, such as developmental disease, joint instability and trauma (Figures 2 and 3). The holy grail for the treatment of OA would involve addressing the underlying condition. However, at present, successfully halting the cascade of events that eventually results in OA is rarely possible and no clear method exists of reversing the pathological process when it has begun.

In addition, the diagnosis of the underlying condition is often made after the OA cascade has already begun. These factors result in an insidious progression of OA.

If we accept we are too late and/or unable to halt the progression of OA and dogs present in chronic pain states then the management of OA can be challenging. However, by using a multimodal approach, many dogs can be successfully managed throughout their lives.

A multimodal approach targets a number of different interventions simultaneously to achieve more effective control as rapidly as possible.

A wide range of treatment choices is available and evidence of proven benefit of the intervention is critical. However, this evidence is sadly lacking in veterinary medicine and one should be sceptical of anecdotal stories of efficacy.

For a multimodal approach to be successful, owner compliance to the plan is essential. The owner has to understand the aims and be willing to commit to the long-term strategy. For success, the veterinary surgeon must set achievable goals and carry out regular follow-ups to monitor and adjust those goals as necessary.

Treatment plans tailored to the individual can be extremely useful in enhancing compliance and achieving goals.

Aim OA Sys (www.aim-oa.com) is a cloud-based management tool that helps tailor multimodal plans to each individual patient. However, veterinary practices have to pay a nominal monthly fee to use the system.

Obesity is a risk factor for OA and vital in its management. Convincing evidence exists that weight reduction alleviates symptoms, so this should always be the first step in OA management5,6. Tackling obesity in patients is difficult as it is easy to alienate clients, but practice weight clinics and nutritional advisors can go a long way to help them achieve this.

Much misinformation exists in the pet-owning and veterinary world regarding exercise modification in dogs with OA. Experimental studies in dogs have shown, in the short term, exercise can worsen the lameness associated with OA7. However, the effect of exercise in the medium and long-term has not been studied. Exercise mitigates the risk of weight gain, muscle atrophy, loss of cardiovascular fitness and loss of neuromuscular training – all of which can worsen the clinical signs of OA.

Therefore, a regular exercise regime should be instigated, avoiding large variation, especially at weekends – the so-called “weekend warrior”. The duration and intensity of the regime should be tailored to the individual. No time limit is placed and no activity is necessarily avoided, unless it aggravates that individual’s symptoms.

High-impact activities – such as jumping, ball chasing and playing with other dogs – are more likely to aggravate certain individuals’ joint pain, but not all. The key is introducing these activities gradually and assessing how that individual dog copes.

Physical rehabilitation and exercise can also be shared with a rehabilitation expert, such as a physiotherapist. It should be noted veterinary physiotherapist is not a protected title in the UK, so it can be difficult to choose an appropriately qualified person. The author would always try to choose an Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Animal Therapy-registered physiotherapist for any rehabilitation programme (www.acpat.org).

Analgesics are the mainstay of medical therapy and the most commonly used agents are NSAIDs. Many are available to choose from and newer additions come to the market all the time. Evidence exists for the efficacy of carprofen, meloxicam, firocoxib, robenacoxib and mavacoxib8-11.

NSAIDs should be given for a minimum of two weeks before their efficacy is assessed and it is worth swapping to another NSAID if one appears to be less efficacious, with a washout period of five days in-between.

As dogs are in chronic pain states, long courses of NSAIDs are usually required and the author uses 8 to 12-week courses to cover acute flare-ups. Eventually, permanent use may be required, which requires close monitoring. All NSAIDs can induce undesirable or even life-threatening adverse effects; however, the incidence of these are low, but must be taken into account.

Although widespread, little evidence exists to support dose reduction of NSAIDs, although some dogs may be successfully maintained on reduced dosages12. The author always recommends full dose unless adverse effects are encountered.

Analgesia can be augmented with adjunctive analgesics, such as acetaminophen (paracetamol), codeine, amantadine, tramadol and gabapentin. Paracetamol can be used safely in dogs when given at the correct dosages (10mg/kg to 15mg/kg every 8 or 12 hours). It has not caused any renal or gastric injury at the recommended doses and evidence of toxicity is not observed until dosages of 100mg/kg were exceeded13.

Studies assessing its efficacy are scarce, however, and it should be remembered formulations of solely paracetamol are not licensed for dogs.

No reports on the isolated use of codeine in OA in dogs have been published, but it has been used in combination with paracetamol as a rescue drug in a clinical trial14. Pardale-V is licensed in dogs for short-term use (five days), but not in combination with an NSAID. Anecdotally, many vets give Pardale-V and NSAIDs concurrently, without adverse effect, but it should be noted this is off licence use.

Amantadine is an N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist and, as such, may have effects on central sensitisation. One clinical trial showed benefit to using amantadine and meloxicam over meloxicam alone for the treatment of chronic OA pain in dogs15. Again, amantadine is not licensed for use in dogs, but can be used where pain is more difficult to control. It should be noted it took three weeks of use to achieve benefit in the clinical trial.

Tramadol and, to a lesser extent, gabapentin have been used as additional analgesics in chronic arthritis, although, again, are not licensed for use in dogs. Limited evidence exists for their efficacy and the author has had limited success with them. Tramadol is a synthetic opioid broken down into at least 30 metabolites; however, dogs do not produce the metabolite O-desmethyltramadol (O-DSMT) that acts on the opioid receptors and so cannot be expected to have opiate-like effects.

Corticosteroids are generally used as intra-articular treatments for OA, but their use is controversial. Conflicting evidence exists on whether corticosteroids are chondroprotective or chondrotoxic. They can have a potent anti-inflammatory effect and significantly alleviate clinical signs, albeit with temporary effect. Therefore, they should be used judiciously and with strict aseptic technique first, ensuring no evidence exists of sepsis within the joint.

Pentosan polysulphate is a semisynthetic glycosaminoglycan that, experimentally, can retard articular cartilage degeneration. However, clinical trials have resulted in mixed reports of its efficacy and the author does not recommend its use.

Mesenchymal stem cell therapy has been marketed to promote regeneration of the articular cartilage, which is difficult to believe if the inciting cause of the OA has not been addressed. Stem cell therapy may have an immunomodulatory or anti-inflammatory effect and early clinical trials have shown some efficacy in dogs with OA of the hip and elbow16,17. Treatment involves the harvest of autologous adipose tissue – extraction of stromal cells – which are then injected intra-articularly. The treatment is a two-stage process involving two anaesthetic episodes and the cost benefit has not been fully investigated.

Autologous platelet therapy has also been promoted for its regenerative effect of articular cartilage, and is easier to use and much less expensive than mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Again, it is unclear how much regeneration of articular cartilage could occur. A blood sample is obtained from the dog, a point-of-use filter is used to recover the platelets and the suspension is injected intra-articularly. One trial showed efficacy in dogs with OA when compared to the control group18, which may, again, be due to an immunomodulatory or anti-inflammatory effect within the joint.

Further, larger studies are required to assess the efficacy of stem cell and platelet therapy – especially in the longer term.

Much interest has occurred in the past 30 years in nutraceuticals for the treatment of OA, with many different ones available. The most common are chondroitin sulfate, glucosamine hydrochloride and essential fatty acids. The evidence for the efficacy of chondroitin and glucosamine in dogs and humans is poor19,20. The author does not recommend the use of glucosamine or chondroitin.

At present, no evidence exists for the use of laser therapy, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, electrical stimulation or acupuncture in the treatment of OA in dogs or humans.

Very few surgeries are available at present that can successfully address the underlying initiating pathology and alter the progression of OA. Juvenile pubic symphysiodesis has been shown to prevent the onset and progression of OA secondary to hip dysplasia, but only in puppies with mild to moderate hip laxity, not in those with severe laxity24.

The clinical significance of this is unclear – that is to say, whether the less severely affected puppies would ever have been clinically affected. Double or triple pelvic osteotomy has been shown to improve hip conformation in dogs suffering from hip dysplasia, but have not been shown to prevent the onset of OA25. Similarly, surgeries for medial coronoid disease, cranial cruciate ligament disease and articular fractures have not been shown to prevent or meaningfully alter the progression of OA. This is not to say dogs do not benefit from these surgeries, but it must be acknowledged the secondary OA is inevitably progressive. Therefore, surgical management is often reserved to the treatment of established OA and salvage surgery can be successful in dogs with intractable pain and insufficient response to medical management.

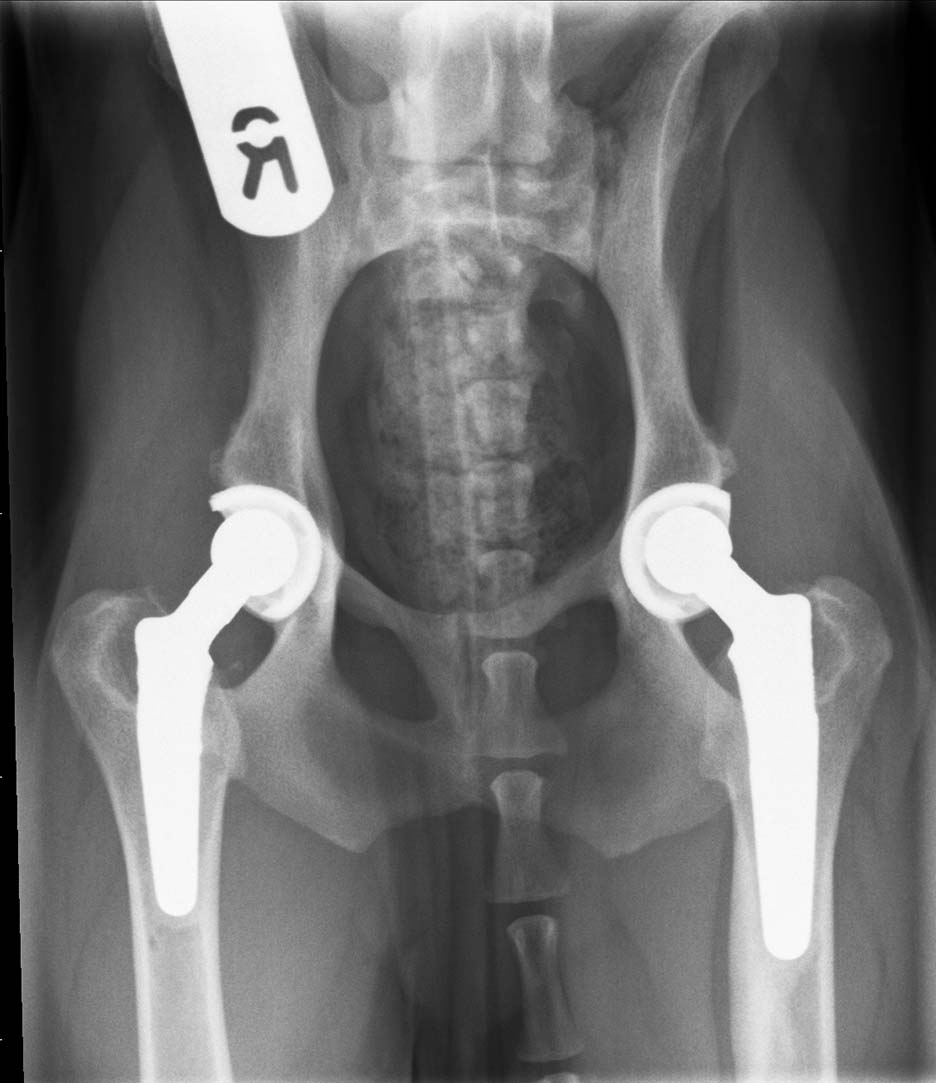

Joint replacement can offer significant pain control and increased mobility. Commercial systems are available for the hip, stifle and elbow. Total hip replacement generally has an excellent outcome and is commonly performed (Figure 4). In contrast, total knee and total elbow replacement are seldom performed, mostly as a result of less encouraging outcomes with significant risk of complications.

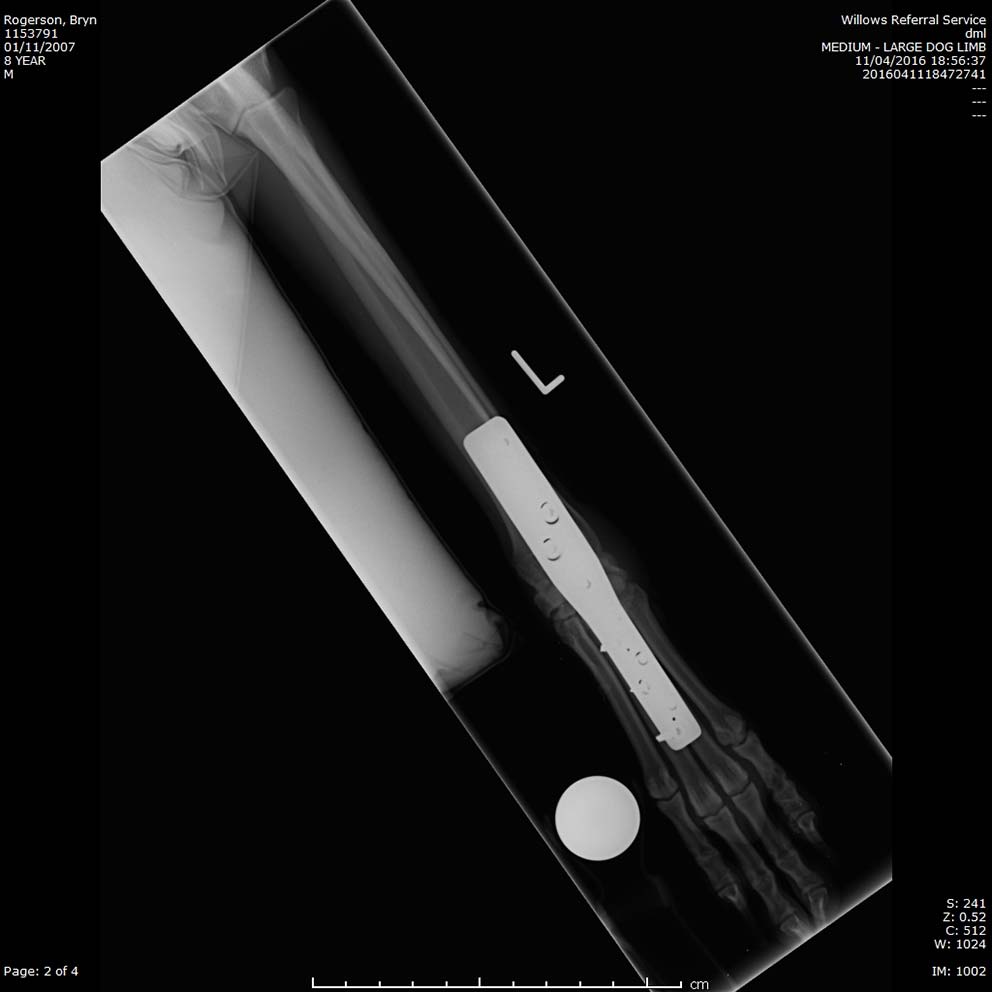

Arthrodesis of the shoulder, carpus and tarsus is reasonably well tolerated in the dog and can effectively alleviate pain without significant effects on mobility (Figure 5). In contrast, elbow and stifle arthrodesis have pronounced deleterious effects on mobility.

Finally, excision arthroplasty of the hip – a femoral head and neck excision – can be considered on clinical or economic grounds and can result in a favourable outcome, especially in smaller dogs, although the outcome is unpredictable.

OA presents real challenges for management, both to the dog owner and vet, and one simple solution does not exist. Developing a multimodal approach that the owner can commit to and follow through is the key to success.