22 Oct 2018

Emmanouil Tzimtzimis, Alasdair Hotston Moore and Kerstin Erles discuss the case of Meg, admitted as a referral emergency with a 10-day history of inspiratory dyspnoea and stridor.

Meg, an eight-year-old female neutered Labrador retriever, was admitted as a referral emergency with a 10-day history of inspiratory dyspnoea and stridor. A first approach with dexamethasone injection and exercise restriction had improved the signs, but these recurred soon with cyanosis.

After successful initial stabilisation with oxygen for two hours, sedation (acepromazine 0.02mg/kg and methadone 0.2mg/kg) was administered to allow a light plane of anaesthesia with alfaxalone 1mg/kg. Laryngoscopy at that stage showed a wide abduction with adequate mobility of both arytenoid cartilages. Based on this, laryngeal paralysis was excluded and the patient was intubated and maintained on isoflurane and oxygen for a CT scan of the neck and thorax.

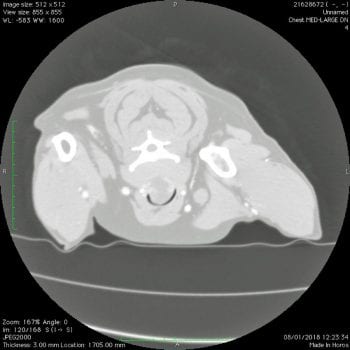

The CT scan revealed a 4cm spherical, intraluminal mass in the distal cervical trachea, obstructing approximately 80% of the tracheal lumen (Figures 1 and 2). The rest of the trachea, the bronchi, bronchioles and lungs were unremarkable. The mass was also visualised with tracheoscopy following the CT scan (Figure 3).

The patient was taken to surgery in the same anaesthetic episode and a midline approach to the distal neck was performed. The affected portion of the trachea was carefully dissected free from the left and right recurrent laryngeal nerves, which were protected during surgery. Tracheal resection was performed at the level of the mass, including four tracheal rings. A large urinary catheter connected with the anaesthetic circuit was inserted through the tracheal tube and directed to the thoracic trachea during resection.

A sterile endotracheal tube was then inserted after apposition of the tracheal edges. Tracheal anastomosis was performed with circumferential polydioxanone 3-0 simple interrupted sutures (Figure 4). Finally, the surgical wound was closed routinely in three layers.

Meg made an uneventful recovery and she was hospitalised overnight on low dose acepromazine, as an anxiolytic and antitussive regime, and methadone. She was discharged the following day on short-term meloxicam and instructions to avoid any neck hyperextension and to be walked only on a harness. Three months later, Meg remains free of any respiratory clinical signs.

Histopathologic examination of the resected mass revealed an intraluminal – extraluminal (Figure 5) low-grade myxosarcoma that was completely excised.

Primary tumours of the trachea are uncommon in dogs1-3. Non-neoplastic, benign and malignant masses have been described, although tracheal myxosarcoma has not been, to the author’s knowledge, reported before. Non-neoplastic masses include parasitic granulomata from Onchocerca species and Spirocerca lupi, haematomata, abscesses and nodular amyloidosis.

Previously reported primary benign and malignant tracheal neoplasms include those of mesenchymal origin (osteochondroma [in young dogs1,2,4], chondroma, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, leiomyoma, fibrosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma), round cell tumours (extramedullary plasmacytoma, mast cell tumour and lymphoma) and those of epithelial origin (adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and seromucinous carcinoma).

Differential diagnosis for this case included laryngeal disease (paralysis, collapse, neoplasia, laryngitis, foreign body, trauma and epiglottic entrapment) and tracheal disease (collapse, tracheitis, neoplasia, foreign body, trauma, oesophagotracheal fistula and tracheal narrowing), although the signalment and clinical signs strongly suggested laryngeal paralysis.

Although tracheal masses are usually obvious in survey radiographs2,5, an intraluminal lesion was not detected in lateral thoracic radiographs performed 10 days before final diagnosis in this case. CT scanning provided a fast and accurate diagnosis, including the exact location, the extent and the relation of the lesion to adjacent structures, as well as the assessment for potential intrathoracic metastasis. Furthermore, tracheoscopy allowed a magnified visualisation of the surface of the mass and an assessment of the degree of dynamic airway obstruction.

Tracheal resection and anastomosis is the only available surgical treatment for solid obstructive tracheal tumours, but a considerable limitation exists on the extent of the resection. With large resections, increased tension would tend to separate the tracheal ends – resulting in healing by secondary intention (granulation tissue) rather than by primary intention (epithelial tissue).

Granulation tissue formation and subsequent scarring may cause tracheal stenosis with signs of recurrent inspiratory dyspnoea. In general, up to 25% of the trachea (8 and 10 tracheal rings) can be removed in a mature dog, although this number may be smaller in young dogs or dogs with primary tracheal disease6.

An interrupted suture pattern for tracheal anastomosis has been shown to be beneficial, as compared to a continuous one in dogs in terms of precision of anatomic apposition and postoperative subclinical tracheal luminal stenosis7. Therefore, simple interrupted sutures were chosen. Polydioxanone, a slowly absorbable synthetic monofilament material, was preferred over non-absorbable material to minimise chances of late granuloma formation and stricture3,8. Regarding the technique of apposition of the tracheal ends, a “split cartilage” technique was used in this case, in which sutures are encircling the divided tracheal rings of the two tracheal ends. This technique has been shown to produce a reliable cartilage healing with minimal luminal stenosis9.

Early postoperative complications include leakage of air from the anastomotic site and subsequent subcutaneous emphysema or pneumomediastinum, infection and seroma formation. Stricture formation from granulation tissue is an important late complication that often requires revision surgery with resection and anastomosis3. No complications were seen in this case, apart from moderate seroma formation observed 10 days postoperatively that resolved completely within the following weeks.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first tracheal myxosarcoma reported in the dog; therefore, the biologic behaviour and metastatic potential of this mass is largely unpredictable. Of the few tracheal malignant tumours reported in dogs, metastasis was confirmed in a very small number of patients5. Malignant tracheal masses should be given a guarded prognosis10. However, the low histologic grading of this mass, the apparent complete resection and the favourable long-term outcome suggest local tracheal resection was curative in this case.