9 Jul 2018

Mario Coppola evaluates the effect of an intra-articular injection in a dog with bilateral coxofemoral degenerative joint disease.

Figure 1. Amber.

It is the most common clinical syndrome of joint pain and dysfunction – accompanied by varying degrees of functional limitation and reduced quality of life – because it is mostly irreversible and progressive5.

Total hip arthroplasty is the mainstay of canine surgical management of coxofemoral OA. Total hip replacement is the most commonly performed and reliable arthroplasty, with good to excellent function achieved in more than 93% of cases6.

The primary approach in the clinical treatment of OA usually involves extensive use of NSAIDs and analgesics – which allows brief symptomatic relief, but provides no apparent disease-modifying effect7-9 – with physical therapy, weight management and exercise modulation.

Previous studies evaluating OA therapy in dogs have suggested NSAIDs often do not provide complete pain relief10.

Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell (ADMSC) therapy has been found to be an appropriate treatment for the hip joint, helping dogs’ gait and their ability to live more normal lives11-13. Additionally, it has been reported injection of mesenchymal stem cells into joints with experimentally induced OA can decrease cartilage destruction, osteophyte formation and subchondral sclerosis, and lead to regeneration of meniscal and articular cartilage14-17.

Stem cells are characterised by their ability to self-renew and differentiate along multiple lineage pathways. They contribute to generating new tissue, are chemotactic for progenitor cells, supply growth factors, make extracellular matrix, help angiogenesis, and are antiapoptotic, anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic. Stem cells contribute to the regeneration and replacement of injured and diseased tissue via cell differentiation, modulation of signalling pathways – via cytokines – to decrease progression of disease, and aid resident stem cell activation and recruitment18,19.

Intra-articular injection of ADMSCs has been shown to have a beneficial effect on canine OA, both inhibiting the inflammatory reaction and promoting cartilage healing20.

In contrast to drug therapy, cellular therapies do not rely on a single target receptor or pathway for action. It functions by secreting cytokines and growth factors, recruiting endogenous cells to the injured site, and may promote cellular differentiation into the resident lineages21,22.

Amber, a five-year-old neutered cavalier King Charles spaniel (Figure 1), has chronic bilateral coxofemoral OA (Figure 2) and been on treatment with an NSAID (firocoxib 8mg/kg every 24 hours) since she was three years old.

History, physical examination, lameness examination – including joint mobility and notation of pain on manipulation – and bodyweight were recorded, and a Liverpool OA in dogs (LOAD) initial visit questionnaire was completed by the owner. The lameness grade was assigned in accordance with a previously described scoring system13:

1 – no lameness observed

2 – intermittent weightbearing lameness

3 – persistent weightbearing lameness

4 – persistent non-weightbearing lameness

5 – ambulatory only with assistance

6 – non-ambulatory

Pain was classified as severe, moderate, mild or absent, according to the dog’s reaction on joint manipulation.

Initial evaluation blood sample and adipose tissue were harvested, and x-rays of the coxofemoral joints taken. Amber was sedated by IV administration of acepromazine (0.01mg/kg) and methadone (0.2mg/kg). Anaesthesia was induced by IV administration of propofol (4mg/kg) and maintained with a gas mixture of isoflurane and oxygen.

A total of 10ml of blood was extracted aseptically and deposited in a serum tube. A sample of adipose tissue was collected from the right inguinal region and sent to Veterinary Tissue Bank for stem cell processing (Figure 3).

Orthogonal radiographs were taken of the coxofemoral joints.

A small fat sample was harvested in phosphate buffer, digested in collagenase solution, filtered and cultured to isolate stem cells over 10 to 14 days until cell numbers exceeded two million. Excess cells were frozen in liquid nitrogen for future use.

For quality control, cytometry was used to characterise stem cells – using markers such as cluster of differentiation (CD)20 and CD34 – with the aim of identifying the typical phenotype of mesenchymal stem cells in culture.

The sample was sent for bacteriology and fungal testing at a laboratory, before being sent for injection into the patient, to be certain of no risk of infection from the cells provided. All work was performed inside a high-efficiency particulate air-filtered laminar flow hood to reduce risk of contamination.

Five weeks after initial evaluation, Amber was sedated by IV administration of medetomidine (10μg/kg) and butorphanol (0.1mg/kg). Skin over the hip joints was aseptically prepared. Arthrocentesis of the hip joints was performed and 1ml of ADMSCs injected into each joint.

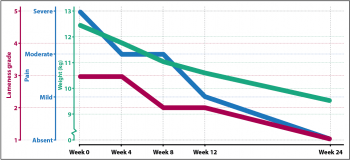

Amber was assessed 4, 8, 12 and 24 weeks post-injection. Evaluation was performed, as aforementioned – recording bodyweight, grade of lameness and notation of pain on manipulation. LOAD follow-up questionnaires were completed by the owner 4, 10 and 22 weeks post-injection.

At the time of first evaluation, the owner reported Amber was manifesting inactivity stiffness, exercise reluctance and change in her ability to climb the stairs, and her mobility was mildly effected by cold, damp weather.

In follow-up appointments, the owner reported the dog showing increased mobility and activity. At the following appointments, the owner reported a gradual improvement as registered on the LOAD questionnaires. Four weeks after the injection, treatment with NSAIDs was discontinued.

On first examination, Amber showed grade three bilateral pelvic lameness and severe painful reaction on passive manipulation of the coxofemoral joints, and weighed 12.5kg.

Post-injection assessment results were:

The LOAD score at the initial visit was 17, but lowered to 15 after 4 weeks, 5 after 10 weeks and 0 after 22 weeks.

OA is the most common cause of chronic pain in dogs, affecting up to 20% of the adult population23. Medical management alone is often not enough to provide pain control, satisfying function and good quality of life. A critical need exists for the development of alternative treatments to stop the progression of cartilage degeneration and stimulate its repair.

In this study, intra-articular injection of ADMSCs was evaluated for treating OA of the hip joints. Results showed an excellent clinical outcome, with return to normal function.

At the first evaluation, Amber was reluctant to exercise, with lameness at grade three, severe pain on hips manipulation and weight at 12.5kg. However, 24 weeks after the injection, the owner reported Amber was active and keen for long walks, her lameness grade was one, she was not painful on hip manipulation and weighed 9.5kg (Figure 4).

Many published in vitro and in vivo studies proved the efficacy of ADMSC therapy in OA11,12,14-17,20. The results of this study show a significant improvement in lameness, pain control and quality of life in the patient, despite discontinuing the treatment with NSAIDs.

A LOAD score of 17 and lameness grade three were registered before the treatment, but both scores were 0 at the time of the final follow-up 24 weeks post-treatment. A placebo effect should always be considered when interpreting owner reports. A caregiver placebo effect was common in the evaluation of patient response to treatment for OA by both owners and vets in a study where the relationship between subjective and objective patient outcome measures were considered24. In a study of 222 dogs with OA, LOAD was considered to be a clinical metrology instrument that can be recommended for the measurement of canine OA, is convenient to use and is validated, and correlates with force-platform data25.

A relevant weight loss was also registered, likely due to the dog’s increase of exercise; she lost 25% of her bodyweight in 24 weeks. It has been reported weight reduction may result in a substantial improvement in clinical lameness26, so it is presumable weight loss played a key role in clinical improvement.

Although this study has some limitations – including the absence of objective patient outcome measures, short follow-up time frame, and lack of control and alternative therapies – ADMSC therapy was found to be an appropriate treatment in a patient suffering from chronic coxofemoral OA, and resulted in a significant improvement in lameness, exercise tolerance, pain on manipulation and quality of life.

Clinical Assist